What It Means When Circus Artists Take Part in Graduate Research Courses

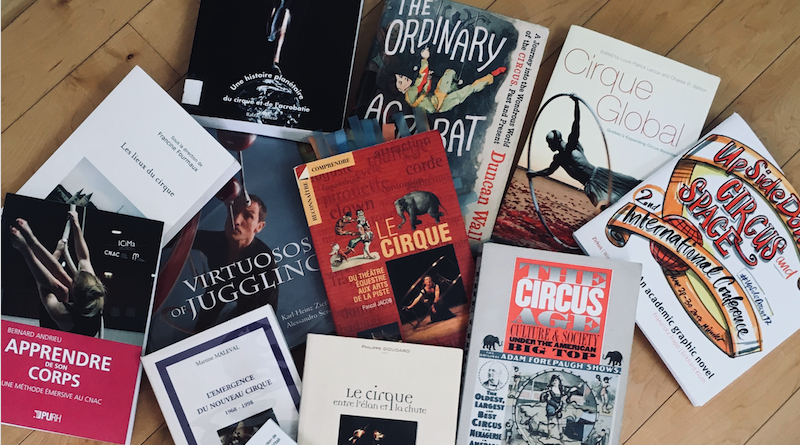

From July 3rd to 13th 2018, over twenty thinker-doers from a dozen countries, all practitioners and scholars of contemporary circus and/or other performing arts, converged onto Montréal during the Montréal Complètement cirque festival to participate in Concordia University’s intensive summer graduate seminar taught by Prof. Louis Patrick Leroux and titled “Experiential learning in Contemporary Circus Practice: Methods in research-creation, action-research and participant observation.” For two weeks, they attended lectures and seminars in the mornings, then in the afternoon, had studio time to work on their presentations or to attend participant-observation sessions as part of a larger research project, and of course, they attended performances in the evening.

In addition to their brief research-creation presentations, the students each produced two to three blogs during this period. We are offering a selection of those blogs. Some are candid, heartfelt, others analytical, some are critical takes, others are musings on students’research. They give a snapshot of what was on people’s minds during the summer intensive.Prof. Leroux and his teaching assistant, Alisan Funk, have also contributed original material to complement the students’ blogs. Check back every Friday until the New Year for an updated article from one of the participants!

As a circus performer, creator, and coach who has turned to academic study, I am well-aware of the scepticism from many in the circus community regarding the place of academic study in circus arts.

In fact, many of us invested in circus arts in order to focus on our bodily experience. When I attended circus school after double majoring in my undergraduate degree, the opportunity to focus fully on my physical and artistic experience was a form of relief. For myself, and I imagine for many others pursuing circus arts, this relief is a reaction to the pervasive reading, writing, and logic skills heavily emphasized in standard school curriculum. We are finally allowed, and empowered, to prioritise and value the experience of our bodies. We relish the nuance of physical experience, the embodied dialogue between performer and audience, the clear line between trying and achieving as we work towards precise artistic and technical skills. It seems, at times, that over-intellectualizing the experience will corrupt the very thing we were escaping to.

Why, then, are so many circus practitioners returning to academic study and investigation?

Why, then, are so many circus practitioners returning to academic study and investigation?

We grow up being taught to sideline our body’s knowledge, and then compensate by being present in the body to the exclusion of intellectual reflection. Perhaps, after many years, the separation between these two things seems to fade. Having nourished the experience of bodily investment, there are questions that remain unanswered, conversations that we want to have, ideas that we crave to investigate, connections that we feel are lacking. Perhaps the desire to include both the body and the mind in our work compels us to return to the hub of critical thinking, the university, to find out for ourselves how each one of us can understand our bodily experiences within the greater context of humanity’s search for meaning.

Around the world, circus studies courses are weaving their way into academic settings. Concordia’s summer program has now hosted two graduate seminars focusing on circus arts. In 2018, students came to the seminar to participate in Practice-as-Research (PaR) in circus arts.

The majority of students in the course came from circus practice. A few others came from other performing arts practices. All were interested in the intersection of doing circus and thinking about circus. As we watched circus shows during the annual Montréal Complètement cirque festival, we engaged in complex discussions around intent, impact, process, representation, and symbolism. Class discussions were informed by observations, multi-national experiences with performing and producing, and the readings which provided frameworks for understanding and reacting to circus performances. The beauty of graduate courses is their emphasis on the question, not the answer; seminar students engaged in critical questioning, and each came to their own conclusions. Without searching forthe right answer – because frankly, is it possible to have a “right” answer in art? – we unearthed informed answers, knowledgeable answers, well-articulated answers, all of which graduate work helps to develop.

Last year, I participated as a student in a similar graduate seminar exploring the landscape of Quebec’s performing arts culture that influenced the development of contemporary circus companies. This year I served as a teaching assistant and guest lecturer for the course, tracking student needs and helping them to find their research questions. Another embedded role of mine: I am also a research assistant on Louis Patrick Leroux’s multi-year project investigating circus dramaturgy, which was intertwined with the Seminar so that students could observe and participate in the process of PaR.

At the end of our intense, compressed course, the students presented their final projects, circus-based research inquiries into questions of personal significance. The process of generating a researchable question and developing a way to research it was as important as the final presentation. Each researcher/performer drew the spectators/co-investigators into their inquiries and justifications. Each provided insight and provoked reflection from the assembled crowd. Several examples to illustrate this blending: performed research of a relationship to circus equipment, leading the audience through their findings visually and verbally; moving the audience/co-investigators to positions in order to physically represent the performers zones of inquiry; an artist challenging the audience to react in order to answer their research question about audience reactions; and many more – each followed by discussion and reflection of what researcher and audience now understand that they did not know before the research/performance.

So, what does it mean when circus artists take part in graduate research courses – focused on practice-as-research in circus arts – during a circus festival – so that they can simultaneously see, ponder, and embody circus practice? It means that the circus community is rejecting an age-old paradigm that insists mind and body are separate. It means that the circus community is embracing the complexity and interconnections that are part of fine arts practice, and that they want to lead the way towards the future of circus arts. And this embodied thought, this thinking practice, is precisely what took place under the guidance of Professor Louis Patrick Leroux, at Concordia University, in the summer of 2018.

Resources for Research Methodology Cahnmann-Taylor, M. & Siegesmund, R. Arts-based Research in Education: Foundations for Practice.New York, NY: Routledge. Damkjaer, C. (2016). Homemade Academic Circus: Idiosyncratically Embodied Explorations into Research in the Arts and Circus. Winchester UK, Washington USA: iff Books. Knowles, J. G. & Cole, A.L. (Ed.), Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research. Los Angeles, California: Sage Publications. Nelson, Robin, Ed. (2013). Practice as Research in the Arts. Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances, London: Palgrave.

All Experiential Learning in Contemporary Circus Practice Seminar articles provided were edited with the help of Caroline Fournier-Roy, M.A. student of English Literature at Concordia.

Related content:Related content: Meanwhile, Backstage...,The Body in Waiting, Circus Summer Seminar in Montreal, What It Means When Circus Artists Take Part in Graduate Research Courses, The More We Learn the Less I Know, A Sequence of Blogs on Expertise and Ethics, Simple Thoughts , Coffee talk with Maddy and Stacey–Finding the Intersection Between Circus & Dance,and The Male Duo in Circus, Un Poyo Rojo & Chute!

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!