Genderful Bodies in Aerial Motion!

When aerial performance became popular in the 20th century, critics reported the confusing gender appearance of its performers. Muscular women were described as mannish and Amazonian while men were observed to be graceful and feminine. Written in three sections, this condensed thesis by actor, circus performer and writer, Lauren Abel, argues that aerial performance is an art form that allows gender to be reconstituted due to its unnatural and seemingly impossible stunts of flight and flexibility.

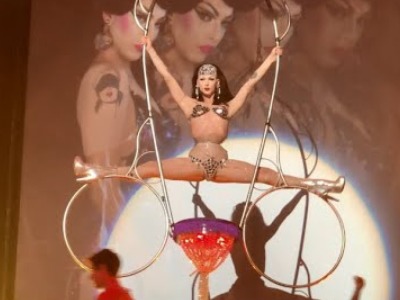

Violet Chachki cracks her whip as male backup dancers pose in obedient unison around her on an international stage during a drag queen world tour. She proceeds to mount an aerial apparatus shaped like a phallic rocket ship on which she performs death- defying stunts in designer heels and a tightly cinched corset. The crowd screams in disbelief and wild admiration.

How did such a performance of gender manipulation and physical skill become so popular with this audience? Is it the risk of failure that holds the spectators’ attention, or is it the excessive feminine beauty paired with assertive stage presence that keeps them in rapture? Has drag performance always been a popular form of entertainment, or did Violet Chachki beat all odds to reach stardom? Her unique combination of aerial skills and female impersonation spark many questions related to circus and gender. To investigate the nature and effect of this intriguing performance form, let us begin at a much earlier intersection of drag and aerial arts.

Describing the Aerialist: How 20th Century Writing Makes Femininity an Impossible Performance

In her essay “Art and Androgyny,” Naomi Ritter compares the writing of two European authors, Jean Cocteau and Thomas Mann, focusing on their views of the circus, particularly aerialists, their gender, and the implications that gender has on art as a whole. Both men muse about the aesthetics and spectatorial effect of aerial performances; however, they come to conflicting conclusions regarding the duality of art. Cocteau, writing in the 1920’s, describes trapeze artist and wire-walker Barbette as god-like: he “transcends both the male and the female in embodying pure sexual beauty.” “Barbette” was the stage name for Vander Clyde, who performed his act in full drag, fooling the audience into believing he was a woman, only to remove his wig after five encores. Cocteau describes the audience’s shock as Barbette “rolls his shoulder, stretches his hands, swells his muscles,” and “plays the part of a man.”

Alternatively, Thomas Mann writes about female acrobats as they demonstrate great skill on trapeze. Moderating his perception through a fictional narrator, Mann describes Andromache, the star acrobat in an imagined Parisian circus, by first marking her appearance of sexual ambiguity. He writes, “She was of more than average size for a woman. […] Her breasts were meagre, her hips narrow, the muscles of her arms, naturally enough, more developed than in other women, and her amazing hands, though not as big as a man’s, were nonetheless not so small as to rule out the question whether she might not, Heaven forfend, be a boy in disguise.” Although this gendered physical assessment implies distaste of the acrobat’s ambivalent form, Mann’s protagonist, Felix Krull, is enamored by Andromache, labeling her an “unapproachable Amazon of the realms of space beyond, high above the crowd, whose lust for her was transformed into awe.” Mann’s notion of the duality of the artist becomes clear as the strong female aerialist both enthralls him and instills feelings of unease.

Ritter’s essay has inspired my investigation of audience’s perception of aerial performance as it became a popular form of entertainment in the 1860s through to the mid- 20th century, as well as how new circus developments in the 21st century are innovating styles of performance that make use of this gender phenomenon and encourage progressive interpretations.

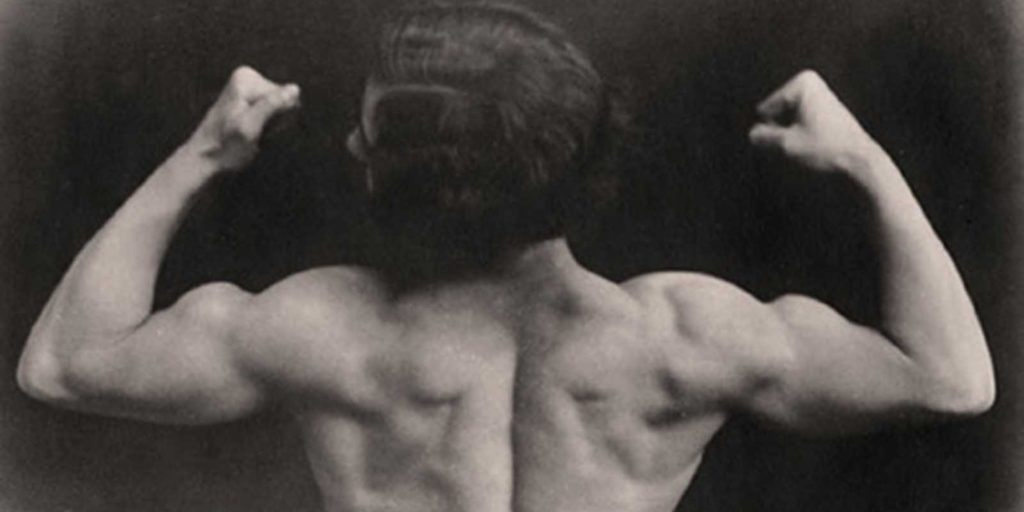

Jules Léotard is widely credited for inventing the act of flying trapeze, the leaping from one swinging trapeze bar to another. He made his debut in Paris in 1895, and became famous as reporters mused over his rippling muscles, birdlike grace, and “calf ankle and foot as elegantly turned as a lady’s.” Although his movement was compared to that of a dainty woman, Léotard also boasted that women admired his body as much as his act. The leotard carries his name even still, as male and female performers, alike, emulated his style and his tricks.

Although men originated the flying trapeze act, women performers quickly populated the circus arena. In 1868 London, Ada Sanyeah debuted with her partner, Samuel Sanyeah. Other English performers also vied for the title of first female flying trapeze artist, including Maude Sanyeah, Zoleila, and Azella. These women performed astounding feats from trapeze to catcher and back to their starting position or executed multiple flips down to a mattress. In doing so, they were often compared to their male counterparts. Azella, for example, was labeled “the female Léotard,” “leaping from bar to bar like a man.” As critics admired their skills, some also condemned women’s participation in circus performance because the nearly nude costuming and “immodest muscular action made the female body seem unfeminine, as did its recklessness.” In the United States, the Ringling Brothers & Barnum and Bailey circus capitalized on the concept of the New Woman at the turn of the century. The circus became home to many women who felt alienated by Victorian norms of domesticity and fashion; however, showmen were aware of the transgressive qualities they displayed and so repositioned them in the public eye to fit into traditional gender categories. These women seemed to live double realities. In the ring, they could be strong and courageous, but in the newspaper reports they feared spiders and mice, they were objects of romance and marriage, and they “desired domesticity over the transient and potentially liberating life of sawdust and spangles.” Circus managers took advantage of this new age of empowered women by positioning them as objects of desire while also policing their public images to maintain a family-friendly atmosphere to attract audiences.

Several occasions of men performing in drag as women further highlight the double gendering potential of aerial performance. Mademoiselle Lulu, born in Maine as Samuel Wasgate, debuted in London 1871 as a graceful and beautiful trapeze artist. In the mid 1920’s Barbette’s act became a sensation because she started as a lovely woman, then slowly removed her clothing to reveal that she was, in fact, a man. Barbette’s goal was not to imitate a women’s trapeze act but rather to design the act “as an exercise in mystification and a play on masculine-feminine contrast, using trapeze and wire as, quite literally, his ‘vehicles.’”

These histories prove that a performed femininity and an internal femininity are not one and the same, just as male muscularity is deemed natural and superior while female muscularity is monstrous and grotesque. Rather than a “natural” association, embodied masculinity looks like bulging muscles and performed femininity looks dainty, cute, and soft, regardless of which sex is performing the gendered gestures. This separation of gender and sex begs the question Judith Butler argues in Gender Trouble: is sex not “always already gender,” is not sex itself a gendered category? While aerial performance proves the separation or elasticity of gender attributes, the positive or negative reactions to these gender performances snap them back into alignment with the assigned sex of the performer. Female aerialists must perform a “natural” version of femininity that looks small, weak, soft, and always smiling in order to successfully match their gender to their sex. If they exhibit other forms of femininity such as those with sexual agency or prowess, they are deemed dangerous and transgressive. Even worse, if women perform with a strength that translates to masculinity, they are labeled “a liminal ‘third sex’ neither female or male” and stripped of their humanity. On the contrary, men performing aerial movement are rarely viewed as transgressive. They are free to exhibit signs of masculinity and femininity (this version seeming more intentional, less demure, and more ideally beautiful) so long as they prove their “true” masculine identity in the social sphere.

The trouble remains that the female body is continuously viewed as either limited or impossible. I argue this point to emphasize the crucial fantasy of flight, one that should be effective regardless of perceived gender, the fantasy of transcendence and freedom that has been and continues to be inspirational to artists of all media. In the magical realm of the circus, the impossible becomes possible; human flight becomes a reality. Also in this realm, we are free to indulge in what is socially considered grotesque, strange, or marginal. Why, then, must we shove these marginal bodies back into social classification and deem them unfit for “normal” society when we leave the tent?

Queer Studies and the Real Presence of Danger: How the Aerialist’s Movements Move Their Spectators

Fundamentally, Maurice Merleau-Ponty provides the phenomenological tenets with which we can begin to construct a theory of how audiences perceive and interpret aerial action. He claims that bodies “catch” movement: “the body catches itself from the outside engaged in a cognitive process; it tries to touch itself while being touched, and initiates ‘a kind of reflection,’ and ‘comprehends’ movement.” Many movement scholars have utilized Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology to assert that the body creates and receives cultural meaning through movement, or rather through sight of another moving body.

While the ambiguous aerial bodies in circus history transgress the gender binary, they do not seem to cross the threshold to the other gender entirely. Rather, they exist in the in-between;, they might even oscillate like a trapeze between appearing male and female. For this reason, I argue that the apt descriptor for these ambiguous aerial bodies is genderful. Although other adjectives for gender nonconforming bodies exist, such as nonbinary or agender, I find that these imply a fundamental lack, a failure to achieve gender. Even genderfluid connotes a moving back and forth between masculine and feminine, never both simultaneously. Genderful implies that ambiguous bodies can inhabit both binary genders as well as the spectrum in between them.

Circus scholar Peta Tait offers that “a visceral encounter with an ambiguous body identity,” like that of a genderful or androgynous aerial body, “bends pre-existing patterns of body-to-body phenomenological exchanges and is at least disruptive of hierarchical patterning. Thus, a lived body might momentarily catch a surprising cultural identity.” A spectator might root for or identify with a performer from whom they would distance themselves in normal life outside the tent.

Movement scholar Erin Manning elaborates on Merleau-Ponty’s assertions of subject formation: while Merleau-Ponty fortifies the subject as something always in relation to an Other, Manning asks us to release our concept of a constant identity. She writes, “If we think identity, we have returned to a stable body. A moving body – a sensing body – cannot be identified. It individuates always in excess of its previous identifications, remaining open to qualitative reiteration.” If we think about identity in this way, as always shifting and reforming in relation to past identities and reacting to new stimuli, a circus spectator’s ongoing formation of self could be heavily influenced by ambiguous moving bodies. Sara Ahmed also invokes Merleau-Ponty in her pursuit of a queer phenomenology. She utilizes his concepts that bodies are not simply “objects in the world” but “our point of view in the world” and that we are oriented toward objects based on historical tendencies, repetition, and what we intend to do with those objects. While we might be tempted to assume that the body orients itself according to the normative – straight – vertical and horizontal axis of the world, Merleau-Ponty and Ahmed reassure us that instead of reorienting itself to fit the world, “the body straightens its view, in order to extend into space.” When we are oriented on a slant rather than the heteronormative vertical axis, we might create our own queer axis with which to perceive objects and bodies. The circus does some of this work for spectators. It queers their preconceived understanding of human abilities, appearances, and gender expressions. Therefore, the circus, specifically aerial performance, allows for spectators who consciously identify on the normative axis to experience and possibly identify with bodies on an oblique axis.

Leo Bersani writes that “the truth of our desires has become the truth of our being.” This concurs with Ahmed’s notion that “we are oriented toward objects as things we ‘do things’ with.” The objects we desire dictate our movement and behavior, and these bodily actions denote who we are, the way we move through the world, our mode of being. Desire is key to subjectivity and drives the complication of gender in aerial performance. Genderful aerial bodies dislodge the audience’s understanding of binary attraction and therefore ask them to disidentify with normative systems of gender, sex, and sexuality in order to enjoy the performance. Aerial bodies work on and against binary modes of reality and prompt spectators to desire them in new ways. They invite viewers to find shared commonality in the margins and identity in difference. José Muñoz explains that queer people have practiced disidentification with mainstream media as a way to remove the shame imposed by normative structures for their transgressive desires. Circus disidentifies with normal reality by allowing bodies to be reoriented in space. Circus asks audiences to check their shame at the door, leave their normative pressures outside the tent, and explore an oblique trajectory of movement through genderful performers.

Beyond the Binary– New Circus and New Understandings

Modern iterations of circus performance, known as New Circus – as opposed to Traditional Circus – are using the unique attributes of gender ambiguity and delight in the grotesque to their advantage. Companies such as Cirque du Soleil, Circus Oz, Bellingham Circus, and Beyond Melanin (just to name a few) intentionally subvert gender expectations by staging innovative and transgressive bodies performing amazing feats. Cirque du Soleil’s Icarus, in the show Varekai, appears as an ambiguous body that seeks assistance from new friends of all abilities to rebuild his sense of self. Circus Oz explores Aboriginal stories in a neocolonial society using humor and stoic acrobatics. Bellingham Circus stages a lesbian relationship full of sexual tension and passion which is not often portrayed onstage, allowing queer audience members to identify with powerful complex women. Beyond Melanin rewrites the social narrative of two black men in a tender love story full of intimate camera angles, floating body positions, and sensual touch.

Some artists who place gender, rather than circus, at the forefront of their expression also use aerial apparatus to evoke strong emotional reactions in the audience. Violet Chachki, a world famous drag queen, crosses the distinctions set for normative sex and gender many times in her portrayal of femininity. She is an AMAB person dressed in extravagant women’s clothes who sells the image of a sexual dominatrix alien woman. She utilizes the extreme risk of aerial arts paired with drag performance to feel intense control of her body and power over masculine-presenting men’s bodies as reclamation of space and sexuality. On top of performing incredible stunts, serving face and finesse, she also makes a strong political statement about the fungibility of gender. Unlike Barbette, Violet does not remind the crowd that she can fit into heteronormative standards. She stands in her power as an ultra-femme genderfluid performer. This bold embodiment of strength and gender manipulation empowers her audiences to live authentically in a society that restricts this style of expression.

Aerial performance sets bodies in motion that appear to defy natural laws that bind humans to the earth and to linear progress. In fact, these bodies use natural laws to manipulate and restructure our perception of stable reality. We can utilize the phenomena of flexible context, identity, desire, and time available in aerial performance to embody the deconstruction of systems of knowledge that appear to be constant or essential. The corporality of circus bodies makes them valuable both as resources for observing and tools for staging the reinvention of established social ideologies.

New Circus aerial performance demonstrates many different tactics to deconstruct and restage socially defined categories of being. By harnessing the fungibility of gender, the historical meaning of racialized bodies, and the nostalgia of space-time, New Circus companies and performers seek to rewrite cultural narratives in hope for a more equitable society that welcomes modes of being and iterations of desire outside the normative binary structures. Aerial motion allows performers to speak to the audience’s flesh, to communicate with the core of their subjectivities and, therefore, create a passage for new understanding of the Other.

Circus performance, especially aerial motion, offers a unique spectacle of “actuality and illusion.” It positions aerialists as both performing subjects and objects of their own movement. This vacillation between subject and object is kinesthetically transferred to audience members as they relate to the physical danger of such high, swift motion. The swinging movement of a genderful trapeze artist hails the spectator to identify with them in peril and in glory, experiencing terror and elation, while also positioning the performer as an object of desire. The confusing combination of identifying with a genderful body and desiring the same body asks audiences to reconsider the strict social distinctions between subject and object, between self and Other. Many phenomenological thinkers explain how our notion of subjectivity is always incomplete because it relies on the presence of and distinction from the Other. Modern capitalist society requires our identities to remain fixed in binary categories, separate from the Other in order to increase productivity. However, this leads to harmful objectification of the Other and casts them outside the norm. Aerial performance allows us, instead, to view bodies in various configurations that take the pressure off these normative categories. It allows us to reorient ourselves in space with the Other and to accept different modes of moving through the world. Under the tent, ordinary people perform extraordinary feats, and spectators find delight in the discomfort of danger. Aerial motion and the illusion of human weightlessness can make us feel stronger and more vulnerable than we ever imagined, so I hope my research and perspective of bodies in flight inspires you to reconsider what and how our bodies mean.

Sources: Naomi Ritter, “Art and Androgyny: The Aerialist,” in The Routledge Circus Studies Reader, ed. Katie Lavers and Peta Tait (United Kingdom: Routledge, 2016), 136–52. 142. Francis Steegmuller, “An Angel, a Flower, a Bird: How Barbette and His Trapeze Once Dominated Vaudeville,” The New Yorker, September 20, 1969, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/09/27/an-angel-a-flower-a-bird. Thomas Mann, Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man, A Signet Book, trans. Denver Lindley (New York: New American Library, 1957),. 157. Mann, 159. Arthur Munby, Man of Two Worlds: The Life and Diaries of Arthur J. Munby 1828-1910, ed. Derek Hudson (London: John Murray, 1972),. 97, qQuoted in Peta Tait, Circus Bodies: Cultural Identity in Aerial Performance (Abingdon [England]: Routledge, 2005), 12. Tait, Circus Bodies, 16-18. John Turner, Victorian Arena: The Performers. A Dictionary of British Circus Biography, vol. I (Formby: Lingdales Press, 1995), 8, quoted in Tait, Circus Bodies, 18. Munby, Man of Two Worlds: The Life and Diaries of Arthur J. Munby 1828-1910. 252, quoted in Tait, Circus Bodies, 20. Tait, Circus Bodies, 21. Janet M. Davis, “Respectable Female Nudity,” in The Routledge Circus Studies Reader, 173–97. 185, 188. Bill Lipsky, “Mademoiselle Lulu: The Wo/Man on the Flying Trapeze,” San Francisco Bay Times, April 7, 2016, http://sfbaytimes.com/mademoiselle-lulu-the-woman-on-the-flying-trapeze/. Steegmuller, “An Angel, a Flower, a Bird.” Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (United Kingdom: Routledge, 1999), 10. Davis, “Respectable Female Nudity,” 181. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Collin Smith (Taylor and Francis Group, 2005),. 107, 165. Tait, “Ecstasy and Visceral Flesh in Motion,” in The Routledge Circus Studies Reader, 308. Erin Manning, Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), xviii. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (London and New York: Routledge, 1958), 5, as quoted in Sara Ahmed, “Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology,” GLQ 12, no. 4 (2006): 543–74, https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2006-002, 551. Ahmed, “Orientations,” 561. Leo Bersani, Receptive Bodies (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2018), 21. Ahmed, “Orientations,” 550. José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999). Muñoz, Disidentifications. Roberta Mock, “When the Future Was Now: Archaos in a Theatre Tradition.,” in The Routledge Circus Studies Reader, 164.

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!