Mapping Contortion in Japan– Part One, A History

I recently published my anthropological research study The Art of Contortionism: An Introduction to and Analysis of Chinese Contortionism in a Historical, Political and Social Context aiming to position the art of contortion in scholarly literature, exploring its history and development, and to open up this valuable field for future discussion and research. With this article, I would like to tie in on my previous work in East Asia and explore the development of contortionism in Japan through an anthropological lens by taking historical and social aspects into account.

In order to map the development of contortion in Japan, it is imperative to encompass historical events that might have influenced the development of contortion practices in Japan. Events to consider are the beginning of the China-Japan relations in the 8th century which sparked the first recorded encounter with circus arts, the moment Japan opened up to the world again after more than 200 years of isolation (1639-1853), enabling an artistic exchange between Japan and the West, as well as contemporary events such as the opening of the first contortion studio in Japan in 2015. During my research of different articles, books and archival circus programs, and in my interview with Ayumi Moco Osanai, the founder of Contortion Studio Nugara Japan, I was able to reconstruct a guiding thread of contortionism throughout the history of Japanese circus and street performances.

Recordings of one of China’s largest cultural encyclopedias WapBaiKe assert that China introduced Sanle, later translated to Sangaku, to Japan in the 8th century, a precursor to what we call circus today and which displayed juggling, pantomime, dance and acrobatics [1|. Having explored the history and the development of contortionism in China in my earlier research, discussing traces that date back to ancient eras around 2000 years ago, an introduction of this art form to Japan in the 8th century is feasible [2, p. 20]. Of particular interest is the question, if there had been contortionists among the Chinese acrobats and if the introduction of circus to a Japanese audience had triggered a continuation of the circus culture, and contortion in particular, in Japan?

In his articleMisemono: Japanese World of Attractions author Dr. Dawid Glownia of the Institute of Journalism and Social Communication of the University of Wroclaw, discovers in detail different disciplines that were part of the acrobatic program of Misemono exhibitions.

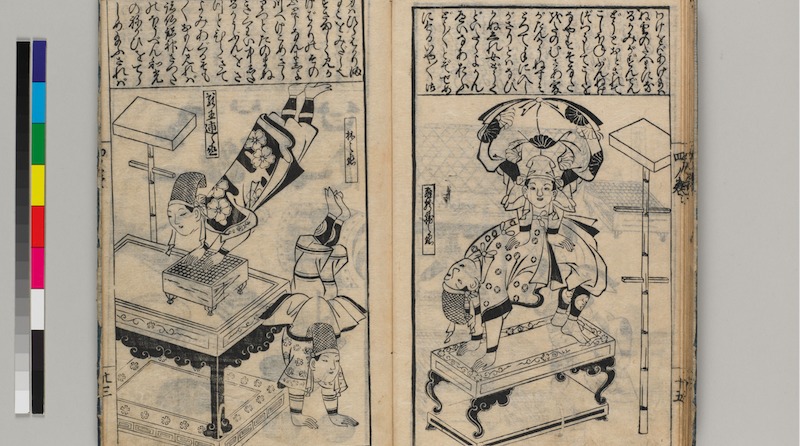

Misemono (literally exhibition or spectacle) became a phenomenon among Japanese audiences. Popular during the Edo period (1603-1868) Misemono’s were spectacles showcasing acrobats, craft shows such as lifelike doll shows, exotic animals, freak shows displaying people with deformities and handicaps, mechanical creatures and other sideshow gaffs. Although the term itself appeared in the Edo era, seeds of misemono shows already developed in the Muromachi era between 1336-1573 [3]. Among the drawings in his paper, Dawid Glownia features one picture of the Illustrator Morishige Furuyama, depicting two acrobats in typical contortion position, balancing on top of each other. These illustrations from the late 17th century reveal evidence that contortionists have been amidst the performing artists, and that body flexibility was practised in Japan already during that era. When looking at those early illustrations of contortion acts of Misemono troupes it is important to keep in mind that in those performances Japanese entertainers sometimes dressed up in Chinese clothes or other foreign clothes to create an exotic atmosphere [4].

Another promising finding is the independent development of Kakubeijishi or Echigo Jishi, the so-called Echigo Lion, performed by young boys between the age of 5-14 who showcased acrobatic tricks such as tumbling, handstands and contortion. It is believed that this art form was developed by villagers in Echigo of the Niigata prefecture during the Edo period, where annual floods repeatedly destroyed the harvest. The children of the villagers performed acrobatic tricks accompanied by musicians who played the flute and drum, in order to gain money and to escape starvation. The costume usually consisted of a hat in the form of a lion’s head decorated with chicken feathers, black satin and red silk. This art form declined during the Meiji era with the installment of compulsory education when child labor was prohibited. Author Akune Iwao presents a collection of authentic images of the performing children of that era in his book Handstand Children: The Kakubei Lion’s Light Technique (translated from Japanese) [5].

Key findings emerge as well from other sources. An increasing number of photographs emerge showing Japanese contortionists in Western exhibitions and travelling circus shows after Japan opened up to the world again in 1853. A photograph published by Numa Blanc, Paris displays the two Japanese child acrobats Yonekichi and Sentaro, contortionists and members of the Hamaikari Sadakichi troupe that appeared at the Exposition Universelle de Paris in the fall of 1867 [6], as well as sketches of the troupe in archival expo magazines [7]. Another article displays a photograph of a group of 19th century Japanese contortionists while discussing the impact of Japanese artistes on the circus world [8]. And then, of course, there are references of contortionism, gymnastics and body flexibility in program notes and sketches throughout Frederik L. Schodt’s invaluable book Professor Risley’s Imperial Japanese Troupe [9].

In conclusion, the main limitation is the lack of written scholarly evidence and this research is therefore based in large parts on the findings of illustrated data such as archival program notes and circus advertisements, photographs of exhibitions, and illustrations from audience members from previous centuries. Based on these findings, I was able to refine somewhat of a timeline of contortion history and its developments in Japan. But what would this timeline be without considering current developments? In part two of this series I will attempt to answer this question during my interview with Ayumi Moco Osanai, the founder of the first Contortion Studio in Japan. We will discuss the establishment of contortion in Japan, its history and its development in the context of globalisation. I am excited to see how this art form will find its place in Japanese culture in the future.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the following institutions who gave friendly permission to use their image material in this article: The City of Edinburgh Council, the Honolulu Museum of Art, the National Institute of Japanese Literature and the International Institute for Digital Humanities. My sincere thanks also go to Yargai Galtat for the translation, and Mr. Mikio Oshima, Frederik L. Schodt, Dawid Glownia and Ayumi Moco Osanai who supported this research series by pointing my investigation into the right direction and by sharing their invaluable knowledge.

In-Text References [1] WapBaike. (2019). Sanle. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] [2] Ala-Rashi, M. (2019). The Art of Contortionism: An Introduction to and Analysis of Chinese Contortionism in a Historical, Political and Social Context. KDP Publishing USA. [3] Glownia, D. (2016). Misemono: Japanese World of Attractions (Original Title: Misemono: japoński świat atrakcji, część 1: Wprowadzenie) [online] Available here. [Accessed: 23.12.2019] [4] Kawazoe, Y. (1996-B). An Insight into Misemono-e in the Edo Period: Prints on Animal Shows. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] [5] Iwao, A. (2001). 逆立ちする子供たち―角兵衛獅子の軽業を見る、聞く、読む. Shogakukan Press, Japan. [6] WorthPoint. (2020). Japanese Acrobats at Paris Exhibition of 1867 (3). [online] Available here. [Accessed 12.01.2020] [7] Momo2011. (2011). October 26, 1867 Paris Expo Japanese Acrobatics. [online] Available here. [Accessed 21.01.2020] [8] Landau, A. (2016). Japan`s Great (and surprising) Circus History- and the Impact of Japanese Artistes on the Circus World. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] [9] Schodt, F. L. (2012) Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe. Stone Bridge Press, USA.

Bibliography Ala-Rashi, M. (2019). The Art of Contortionism: An Introduction to and Analysis of Chinese Contortionism in a Historical, Political and Social Context. KDP Publishing USA. Awaji. (2020). Awaji Art Circus. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] Foster, M. D. (2008). Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai. University of California Press. Furuya, A. (2007). Koumori To Namekuji No Utage Octopus Boy [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] Glownia, D. (2016). Misemono: Japanese World of Attractions (Original Title: Misemono: japoński świat atrakcji, część 1: Wprowadzenie) [online] Available here. [Accessed: 23.12.2019] Kawazoe, Y. (1996-A). Reading Edo Show Art. (Original Title: 江戸の見世物絵を読む) [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019]Kawazoe, Y. (1996-B). An Insight into Misemono-e in the Edo Period: Prints on Animal Shows. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] Landau, A. (2016). Japan`s Great (and surprising) Circus History- and the Impact of Japanese Artistes on the Circus World. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] Larsen, B. (2019). What is Noh? Complete Guide to Noh Theatre. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] Markus, A. (1985).The Carnival of Edo: Misemono Spectacles from Contemporary Accounts. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 45(2), 499-541. doi:10.2307/2718971 Momo2011. (2011). October 26, 1867 Paris Expo Japanese Acrobatics.[online] Available here. [Accessed 21.01.2020] Oshima, M. (2020). The Japanese Society for the Study of Circus. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] Sawari. (2020). NPO International Circus Village Association. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] Schodt, F. L. (2012) Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe. Stone Bridge Press, USA. Utagawa, T. (2020) Utagawa Toyonobu: Acrobats - Museum of Fine Arts - Ukiyo-e.[online] Available here. [Accessed: 05.02.2020] WapBaike. (2019). Sanle. [online] Available here. [Accessed 23.12.2019] WorthPoint. (2020). Japanese Acrobats at Paris Exhibition of 1867 (3). [online] Available here. [Accessed 12.01.2020]

Links for photo material mentioned throughout the article: 17th Century Contortion sketch --Earliest recording so far. Japanese child acrobats --(Yonekichi and Sentaro), members of the Hamaikari Sadakichi troupe that appeared at the Exposition Universelle de Paris in the fall of 1867. Group of 19th Century Japanese Contortionists Sketches of Contortionists at Paris Expo 1867 Ukiyo-e of Japanese Contortionists during Edo Period Octopus Boy Misemono. Meiji Circus.

Feature photo image A: National Institute of Japanese Literature, Title: Shinpan yakusha e-zukushi (late 17th Century), Artist: Morishige Furuyama. (CC BY-SA 4.0) Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!