Last Waltz: Developing a Methodology for Partnering in Aerial Dance

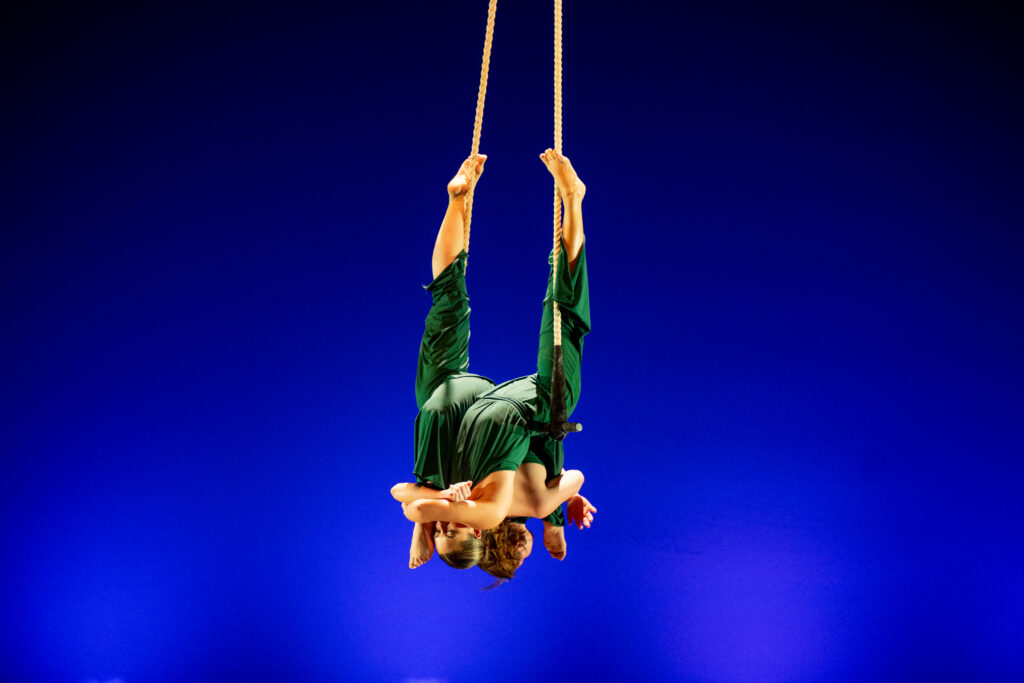

My long-term aerial dance partner and I originally choreographed the trapeze duet, Last Waltz, in 2010. The work investigates the merging of ground and air spaces and the relationship between two movers supporting one another in the air. While restaging Last Waltz with four undergraduate students in a semester-long dance performance course in 2020, I developed a methodology for training partnering in aerial dance. This article is a summary of the project’s practice as research, training progressions, and results. It offers practical ways in which coaches and choreographers can implement performative intention during the creation process rather than an afterthought to the functional movement of aerial arts.

In this article, I use the term “aerial arts” as an umbrella for movement practices that occur in the air through use of a suspended apparatus, regardless of the training and performance context. I use the term “aerial dance” to denote aerial arts that take place within dance training and dance performance settings rather than a specific set of aesthetic values or skill vocabulary. Due to safety considerations inherent in the aerial arts, including the risk of falling, beginning training typically focuses on individual skill acquisition and solo performance. Training for partnering, defined as two dancers sharing one apparatus, involves re-calibrating foundational aerial skills while sharing space and weight with another person. It also involves a shift in perspective from focusing solely on one’s own personal safety to attending to the well-being of another.

The student performers in this project train aerial dance within a Bachelor of Arts in Dance degree program. In addition, they train in ballet, ballroom, improvisation, jazz, modern, and tap and perform in dance concerts that include choreography from these genres. My own aerial arts background is a mix of dance and circus influences. My first experience with aerial arts was as an undergraduate in a college dance program, and I later pursued advanced training at a circus arts institution. I have worked in a range of performance settings, from theme parks to concert dance to corporate entertainment, and have taught in recreational aerial arts studios as well as college dance programs. Although the methodology I share in this article draws on exercises from a modern dance perspective, I believe that it could be useful for practitioners in other aerial arts contexts as well.

SOFT SKILL DEVELOPMENT

This practice as research aims to address my own tendency to default to a traditional skill-acquisition-based training model, which is useful for safety and expediency in learning new skills within the short time frame of an academic semester but is limited in cultivating cognitive and creative skills for artistry in performance. I have noted a tendency in past experiences as both performer and choreographer to layer expressive intention onto functional movement as an afterthought rather than as its genesis. In this choreographic project, the expressive intent of female friendship, support, and interdependence is communicated through the functional medium of aerial partnering vocabulary. While skill acquisition certainly plays a role in the overall training program, a focus on embodying soft skills in rehearsal allowed for a satisfying marrying of function and expression in both process and product.

Definitions of soft skills vary, but generally include a range of personal/cognitive skills–such as taking care/managing oneself, problem-solving, flexibility, and adaptability–and interpersonal/social skills–such as communication, negotiation, cooperation, and collaboration–as categorized by The Empowering Dance Research Report (2020) (10). These skills are non-technical and transferable across careers and industries. The report also notes that “although dance practitioners implicitly apply soft skills, they may not always be aware of them and their positive transferable impact”(3). In this project, I explicitly emphasized soft skills throughout rehearsals, rather than students developing these skills as a happy by-product of participating in the process.

The primary soft skills I identified as necessary for successful embodiment of the choreography were communication and problem-solving. Merriam-Webster defines communication as “a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behavior” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Within the scope of this project, I further define communication as the ability to express one’s needs and listen to the needs of another person. This includes verbal communication, as in talking before, during, or after execution of an aerial skill, but more importantly, nonverbal communication through visual, tactile, and kinesthetic means while moving together in the air. In performance, nonverbal communication such as eye contact, pressure of touch, or visually noting the position of another person’s body in space is an invaluable means of gathering information. The ability to continually exchange information in the moment with a partner is tantamount to taking care of oneself and one’s partner in training and performance.

Many soft skill inventories include problem-solving/creative problem-solving and collaboration separately. However, I identified collaborative problem-solving as a necessary skill for training aerial partnering based on the mutually dependent relationship of the partners and the heightened risk of aerial work. Collaborative problem-solving indicates joint decision-making to reach a mutual goal with positive outcomes for both partners, whether that goal is learning a challenging skill in rehearsal or executing choreography in performance.

This project’s focus on developing soft skills concurrent with training choreography-specific physical skills aligned with recent circus training scholarship that supports an integrated approach including cognitive training alongside traditional behaviorist training (Burtt and Lavers2017, Tucunduva2021). Although these pedagogical studies do not address the application of integrated training to aerial arts, or duets, specifically, they do point to important factors for consideration in the design of an overall cognitive, creative, and technical training program for aerial arts.

TRAINING PROGRESSION

The Language of Dance concept degrees of relating served as a loose theoretical framework for structuring the project’s training progression. [1] Rehearsal exercises began with nearness (proximity) and progressed to contact (touch) and support (supporting the partial and full weight of a partner).

LOD degrees of relating–nearness

The first exercise that I used in the rehearsal process was “mirroring,” a familiar partner exercise for many students either from dance improvisation or from childhood games, serving the dual goal of preparing the body physically for aerial work while also developing visual communication among partners. I guided students through familiar ground-based warm-up exercises with a focus on staying in sync in time and space standing across from a partner. I occasionally incorporated movements that required them to look away from each other (e.g. dropping the head in forward fold) and then reconnect with their partner’s gaze (e.g. stepping forward to lunge).

With visual communication skills heightened, warm-up then transitioned onto the trapeze itself with familiar tasks like tucking under the bar and climbing to stand. In this first experience working with two bodies sharing one trapeze, students must renegotiate foundational skills side-by-side with their partner and become comfortable having less space available to place their own body parts on the apparatus. When first attempting these skills, partners primarily rely on verbal communication to coordinate timing. As they become comfortable with the mechanics, they transition to using visual cues–watching one another’s hands and making eye contact. Finally, experienced partners may not focus directly on visual cues, but rather utilize a general sense of their partner’s position in space relative to their own. The heightened risk and consequence of mirroring in the air also underscores the necessity for collaborative problem solving as addressed in the following exercises.

Next, we focused on the dance concept levels in space that defines possibilities for movement in low, middle, and high zones. Low being the area around the floor (lying, crouching, crawling), middle as the zone of everyday movement, and high, the elevation accessed through jumping, partner lifting, or a prop (Blom and Chaplin 1982, 32). In the dance improvisation game “sit, stand, lie down,” a trio of movers explores these levels. Each trio assumes a starting position with one student pre-set in each position: sitting, standing, lying down. Students begin to move and reconfigure the starting position without speaking. At any given moment, the trio must have one person sitting (middle-level), one person standing (high-level), and one person lying down (low-level). At first, one person moves at a time andthen arrives in stillness, but the game may progress to overlapping waves.

Transferring levels in space to aerial dance, the zones are defined by the structure of the trapeze. Low is the space below the bar, usually accessed by hanging from body parts such as hands, knees, feet, or elbows on the bar. Middle is the space directly above the bar, usually accessed by supporting the weight of the pelvis on the bar as in sitting or balancing on the front of the hips or sacrum. High is the space above the bar at a standing height, usually accessed by standing on the bar or fully transferring the weight of the body onto the ropes, releasing lower body contact with the bar.

In adapting “sit, stand, lie down” for aerialists sharing the limited space of the trapeze, I created the game “narrow, wide, side, side” that challenges students to engage in open-ended problem-solving. Before the game officially begins, students warm up individually using the basic positions of knee hang, sit, and stand, but manipulating each of these positions with legs narrow, legs wide, or the entire position shifted to one side of the bar or the other.

In the first round, partners collaboratively solve the problem of arriving in a multi-level configuration by pre-planning their positions (e.g. one partner will be in a narrow stand in the center of the bar with the other partner in a wide knee hang around the standing feet). The next round challenges students’ collaborative problem-solving ability by limiting verbal communication. One partner initiates a position on the trapeze and the other partner responds in the moment with a coordinating position. Each partner is free to move from position to position as they choose while the other partner responds accordingly. As in “sit, stand, lie down,” the game begins with one person at a time moving and arriving in stillness, but may progress to partners moving in overlapping waves. The increased complexity of each iteration encourages partners to rely on visual cues and kinesthetic awareness to make choices in the moment. To be successful, students must consider how their choices affect their partner, as success in the game is an appropriate configuration of two bodies on the trapeze, not any single body position.

LOD degrees of relating–contact

The improvisation exercise “stick dance” marks the transition from being in proximity with a partner to touching a partner. It introduces tactile communication through the shared medium of a stick while working towards the mutual goal of keeping the stick in the air. A three-foot long, ¼-inch diameter wooden dowel provides a physical connection between partners without requiring physical contact. Each partner places the tip of an index finger onto one end of the dowel. Without talking, partners must use enough pressure to keep the stick parallel to the floor and from falling to the ground (Smith 2016).

Once partners figure out how to match pressure, they can begin to send and receive pressure unequally in order to move through space as a unit. For instance, when one partner sends more pressure through the stick and the other partner receives this with decreased pressure, the pair will travel. Eventually, this modulating pressure and maintaining contact can evolve into an improvisational dance in which partners communicate nonverbally to stay in place, travel, change levels, or turn.

LOD degrees of relating–support

With a heightened sense of tactile communication, students are sufficiently prepared to begin training choreography-specific skills supporting the partial weight (e.g. knee/neck cradle) and then full weight (e.g. Sleeping Beauty) of a partner in the air. Once students demonstrate proficiency in a variety of partial support skills, they can then begin to explore full support skills that fall under more traditional circus duo work with clear base and flyer roles designated for each partner.

In rehearsals, each dancer trained both base and flyer roles in all partner configurations for multiple weeks before I specified individual roles and later specific partnerships. Different body shapes, proportions, and heights require subtle adjustments to the connection positions and offer valuable learning opportunities for all regardless of final casting.

RESULTS

The results of this project came from within the training process as well as a culminating performance. Throughout the preparatory exercises, I gave the dancers explicit permission to weigh their options in the moment and make appropriate choices in the air without the fear of “getting the choreography wrong” and without the pressure of “pushing through” regardless of the consequences. One flyer noted that if she did not feel a strong flex of the base’s foot, she kept one hand on the bar instead of squeezing both arms overhead for a full support moment. Or if she had released both hands and felt the base’s foot quivering, she exited the position quickly. This valuing of student agency was essential for safety and success in the rehearsal process and live performance.

Furthermore, I used my own perception of the students’ safety during the performance as a means to evaluate the outcome of the project. With the pressure of an audience, performers may be tempted to shift their focus from their partner to the audience. Although students initially moved through the opening of the piece with a bit more speed than usual (most likely due to nerves), I was never concerned for their safety.

Beyond this functional baseline, the students shared their own measures of success in connection with their partner. One student said that a feeling of trust in her partner made the performance feel satisfying. Another described feeling relaxed despite the demands of the choreography due to her complete trust in her partner. In a cast discussion after the performance, a performer recounted that the tights of her costume became snagged around the trapeze bar, momentarily preventing her from moving forward in the choreography. Her partner sensed that something was off, they made eye contact, exchanged an imperceptible nod, and held their position until the tights became free, even though this caused them to be later in the music than usual. I consider this skilled navigation of the moment another mark of success for the pedagogy and methodology introduced in this project.

The final measure of success for this project was the embodiment of the expressive statement of the piece. Students acknowledged that trust in their partners not only allowed them to achieve the mechanics of the skills, but also the artistic expression of the choreography. One partnership described their interpretation of the piece as two friends going through life while having each other’s backs. Another partnership described a sense of being there for each other and helping one another to shine. As co-choreographer and performer in the initial performance of the piece, I felt these comments echoed my own sense of friendship and support from the original artistic intent.Ultimately, Last Waltz is about more than a sequence of steps—it is about experiencing a deep and satisfying connection with one’s partner.

Reflecting on the outcomes of this project, I believe that the progressive Language of Dance concept degrees of relating is relevant for introducing partnering in aerial dance, particularly because it may be tempting for a choreographer to jump into the mechanics of complex skills (e.g. due to time constraints or a desire to ensure that dancers are adequately conditioned) rather than indulging in a broad preparatory process. The methodology of this research focused on developing soft skills in communication and problem-solving within this progressive framework, integrating physical skill training with cognitive and interpersonal approaches. Future directions for this pedagogical approach may include introducing creative activities and improvisation exercises to circus coaches and trainers who do not come from a dance background and studying the effects of incorporating these into their training approach.

[1] Language of Dance (LOD) is a system for movement literacy with common terminology for writing dance using symbols as developed by Ann Hutchinson Guest (Guest and Curran2008, xxxiv-xxxv).

This is an abridged version of an ‘Original Manuscript’ of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in 2023 on Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, available online:10.1080/19443927.2023.2187871

REFERENCES Blom, Lynne., and L. Tarin Chaplin. 1982. The Intimate Act of Choreography. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. Burtt, Jon, and Katie Lavers. 2017. “Re-imagining the Development of Circus Artists for the Twenty-first Century.” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, 8:2, 143-155. doi:10.1080/19443927.2017.1316305 Empowering Dance. 2020. Empowering Dance Research Report. CC BY 4.0. http://empowering.communicatingdance.eu/files/EmpoweringDance__Project_Report.pdf Guest, Ann Hutchinson, and Tina Curran. 2008. Your Move. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. Merriam-Webster. n.d. “Communication.” In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/communication Smith, Jennifer. 2016, Aug. 5. “Making Contact: Creating a Space for Touch” [Conference session]. Dance Science & Somatic Educators Conference, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT. Tucunduva, Bruno Barth Pinto. 2021. “An Integrative Methodology for Circus Training Based on Creativity and Education on Physical Expression.” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, 12:4, 499-513. doi:10.1080/19443927.2021.1899973 Main image: Performers - Haleigh Green and Hadiya Williams; Venue - University of Georgia, New Dance Theater; Photographer - Jason Thrasher; Lighting designer - Christian Deangelis

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!