Cirque de Demain: The Wings’ Beat of Tomorrow’s Circus

In the more than four decades since its inception, Le Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain has become one of the major happenings of the circus world, showing us year after year the constant evolution of our art form. In this review, Raffaele De Ritis offers us a glimpse at the 42nd Cirque de Demain festival (Paris, January 26-30, 2023), as well as its story and the ever-changing circus.

To understand the impact of Cirque de Demain, this year at its 42nd edition, it is helpful to apply the theory of how the beating of a butterfly’s wings can generate a tornado.

The flirtation of French culture with circus is well-established over the centuries, with countless influential fans in the literary and journalism worlds passing themselves the torch through history. In the post-WWII years, the chiefest of those characters was Louis Merlin (1901-1976), a seminal pioneer of radio broadcasting, who in the 20s had created La Piste, a fundraising association to assist financially the needs of the circus community. Merlin once a year turned into a ringmaster to preside over the benefit soirée Gala de la Piste, which showcased the world’s top circus acts. For the event, he inherited the iconic blue frock coat of theMonsieur Loyal lineage, a ritual tradition transmitted through Parisian ringmasters for a century.

After Merlin’s passing, his pupil Dominique Mauclair (1929-2017) paid tribute to his memory with the Bourses Louis Merlin, a grant to be awarded to young artists under 25 during an evening of performances in front of a jury. The first “Bourses” edition was launched as a single informal day at the Cirque d’Hiver on a January evening in 1977 and was more or less ignored by the community, with not even 400 people in the audience and mostly French circus youth in the competition (although the winners were The Wee Geets, a family of hand-balancers from Colombia). After three years, this event took on the title of Cirque de Demain.

At this time, the prevailing idea of “circus youth” corresponded to the kids of circus families and, if circus was considered to be an international community, then specific occasions of international gatherings were scarce (the Monte-Carlo festival, started in 1974, being the sole example). Slowly, however, the butterfly started to work its miracle. And Mauclair, an eclectic, open-minded globetrotter, prolific writer, and bon vivant—think a sort of Hemingway of the circus world—was more than sensitive to cultural exchanges.

The festival began to attract unexpected newcomers to the classic ring: mimes from the street scene, such as a then-unknown David Shiner, and; the results of the very first circus schools—the graduates of Gruss’ school or Fratellini’s, as well as, later on, of those in Montreal, or the Big Apple kids from Harlem. Circus directors began to congregate in Paris yearly, doubling up on the Monte-Carlo trip. Here they were sure to feed their programs with fresh and unpredictable revelations from new performers.

It is “the Demain” that started such circus legends as Anthony Gatto or the Alexis Brothers. By the mid-80s, disruptive newcomers such as Roncalli and Cirque du Soleil looked here to cast their first shows. Furthermore, the official credibility of the Paris festival helped to make it the first place ever to reveal talents from closed-off circus empires like China and Mongolia. Later, some of Mauclair’s selections among competing artists started to spread the emerging concept of “artistic direction” in a circus act (something relatively new to the field), as with the Russian avant-garde of Valentin Gneuchev in the 90s. Many iconic techniques of our day, from the Cyr wheel to aerial silks, first saw the light at Demain. Before even the notion of “new circus” arose (Mauclair himself is said to be the first to use “nouveau cirque” expression as an artistic tendency), the Paris festival foresaw a global model of transcultural circus: circus beyond geopolitical borders, practice identities, and aesthetic categories.

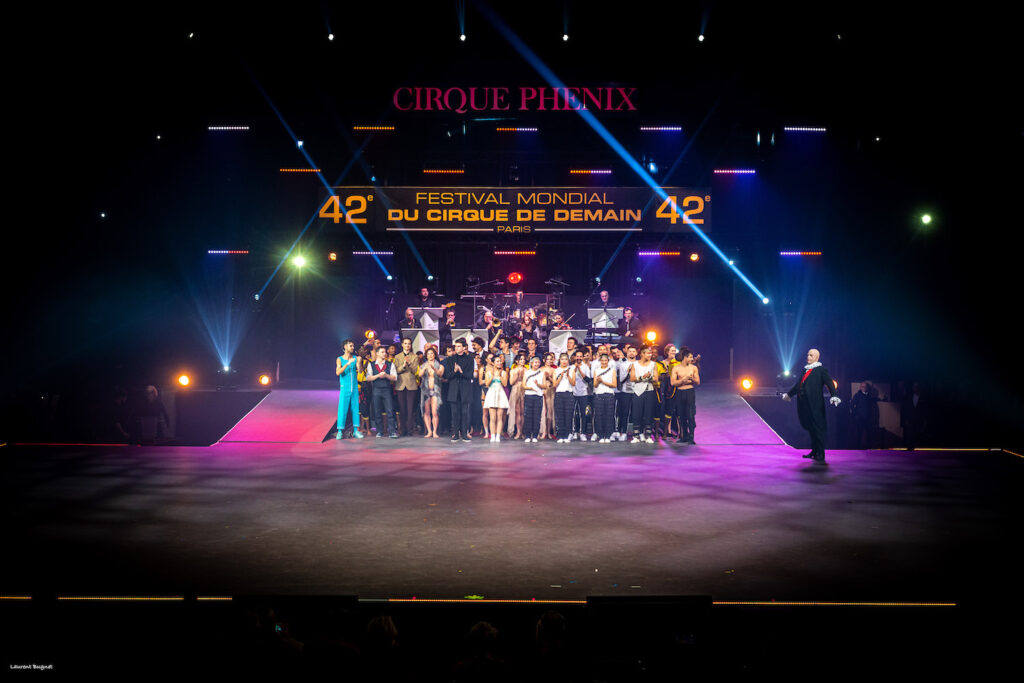

Held annually in different French circuses (mostly under Gruss’ big top, later on at Cirque d’Hiver), the Cirque de Demain Festival entered a new era when Mauclair discreetly retired; in 2006, he was the last gentleman ever to dress in that glorious, two-century-old blue coat. By the 28th edition, the festival organization passed into the hands of long-experienced and sensitive impresario Alain Pacherie—a man with a curious, intelligent gaze on global circus culture, who benefits from the inspired artistic direction of Pascal Jacob, prolific writer-collector and designer for some of the world’s most lavish circus productions of the last two decades. And Pacherie’s own Cirque Phenix—the world’s largest big top active as a circus—became the new Festival home.

Festival in a new era, acts in new forms

During its 42 years of existence, the Cirque de Demain festival has shifted in shape and style according to the times and industry mutations. With increasing demand for and emphasis on creativity to be selected to compete, the participation of circus families has gradually disappeared (strangely, as they are well and lively in most festivals and programs), and with them the animal acts. The worldwide spread of circus schools generated a fresh wave of performers while also meeting the rise of a new market: the cabaret renaissance of central Europe in the 90s (followed a decade later by the United States). Furthermore, the maturity of the companies and schools in Quebec and the actualization of creative approaches from Ukraine, Russia, and China have too contributed to reshaping a new deal for the circus arts.

In Mauclair’s steps, the Pacherie/Jacob direction gained the merit to amplify a less Western-centric vision of circus, opening the horizon toward both the less-explored acrobatic geographies like the previously oft-neglected countries of the Far East and a wider perspective on South America and Africa. The classic act format is today kept as the Demain exhibitive standard but, fittingly for a festival centered around modernity, its content and culture have changed a lot.

Today the industry for proper circus “acts” is somehow shrinking. Acrobats from circus schools tend to form their own companies to create shows in evening-length formats; classical circuses worldwide are touring less and less. The large Parisian cabarets area disappearing race (only the Moulin Rouge still features up to four acts), same as the casino showcases in Vegas. But new areas have emerged and demanded new approaches. Cirque du Soleil remains evidently the planet’s largest employer to preserve the circus act format. And Germany has generated at least four large circus/cabaret circuits (GOP, Palazzo, Roncalli, and Stardust), as has Spiegelworld in the US, in doing so providing employment to hundreds.

Anyway, the average eight-minute act still endures as the “perfect formula” for a festival presentation. It is always interesting to see how the new generations are approaching this time-codified format. The classic act structure was mainly generated by last century’s cross-pollination between circus and variety/vaudeville. Its secret recipe resides in a balance of seamless rhythm, interesting performance techniques, convincing characters, appealing visuality, and audience involvement.

The modern cabaret industry has pushed acts toward a stronger intimacy and a more adult-oriented, sophisticated aesthetic; the artistic pedagogy of circus schools emphasized the research on movement, with slower rhythms and introspective transitions. The expanding access of circus creations to the theatrical and cultural circuit has developed into the recent attempts toward a “circus dramaturgy.” It is not rare that acts created for Cirque de Demain are the extracts of longer-form creations.

Today’s artists’ research on choreography is perhaps at its highest point in circus history; their sensitivity to taste in music is incredible, as well as is their taste in lighting, props, and engineering. This does not always give rise to the same quality in the costumes. (Also missing sometimes is the sophistication of makeup and hairdressing, especially in larger venues. But Soleil and others are always ready to fix that issue in the case of big-time engagements.) If we compare the acts at Demain with the classical style of act, we almost always see a fourth wall being raised between the audience and the performers’ inner narratives. Perhaps this is ironic, given that circus was originally an avant-garde choice for its spontaneity and immersiveness. Despite this, Cirque de Demain stays unique in the circus world as a four-day dive into humanity, freshness, talent and imagination.

The 42nd edition

The festive spirit in the crowded Phenix big top is peculiar; nowhere else does an audience formed by thousands of circus students from around the world cheer like a football stadium crowd for their peers and idols onstage, met with reactions far from the standard circus show (the closest comparison being perhaps from the golden age of the Ringling Bros. Circus’ arena tours). This exchange of electricity is strengthened by the organizers’ fidelity to a few classic codes of circus. The ring is evoked by the central performing space of a black elevated square: a welcoming, neutral monolith synthesizing the multiple spatial identities of actual circus. Red velvets are an essential remembrance of the ceremonial side, as is the live band of Francois Morel, lending their support not only to the finales and transitions but also several of the acts; the parades; and the flamboyant emcee, Calixte De Nigremont, that the audiences have adored for years. Flags and smiles are everywhere, shining under the rainbow of a most impressive lighting system.

Whereas, around the planet, circus festival juries can become predictable company in and of themselves, and perhaps not one always open to those outside the strictest circus logics, the Parisian judge’s panel is a fresh perspective made up of different points of view in a brilliant attempt to evaluate circus as a proper art form. 24 acts from 20 countries were competing this year, each of them with the opportunity to perform twice, for a total of four selection shows in three days, plus the Award Gala on Sunday.

The main award, the Gold Medal, wentex-aequo to two emerging circus cultures: one to Hng Tean Leong, the first-ever artist from Malaysia to appear in a circus festival, for his advanced skill set on the diabolo (still seemingly one of the most widely practiced specialties in the Far East). The other gold went to Troupe Kelfe, coming from Ethiopia, one of today’s most interesting circus landscapes. Their incredible energy and leaping skills were displayed in a nowadays mostly forgotten technique of combining teeterboard with risley. Their effort is just as well remarkable in the seamless choreography and the original DJ music.

Thepalmarés in some years also includes a Grand Prix above the golds, awarded for outstanding achievement. It went this year to the flying trapeze act of the French company La Tangent du Bras Tendu. If flying trapeze is still lively in the Americas, it is almost disappearing from Europe (with some notable exceptions in Russia or Italy). As a discipline, it is unlikely to be learned outside of circus families and is very demanding for a school program. French contemporary circus, however, developed a side tradition with the success of companies such as the Arts Sauts. This winning troupe is epic, epic in concept, size—a dozen flyers—and technical proportions. The dramatic theme is resistance as opposition to dictatorship (the company’s name, in fact, translates into “the tangent of an outstretched arm,” meaning the mocking gesture called the “bras d’honneur”). If seemingly ambitious, the result is attractive with a light and clear symbolism, performed to a soundtrack not less than Chaplin’s “Great Dictator” or Stravinskij’s “Rite.” The prodigious display of technique evolves into the juxtaposition of a system of aerial cradles over a classic flying trapeze display (as per the seminal technical style that emerged from the North Korea State Circus trapeze troupes in the 1980s). The combination of evocative narrative, classical music, and aerial architecture is not without remembering the legendary “Cranes” from the golden 1980s of Russian modern circus.

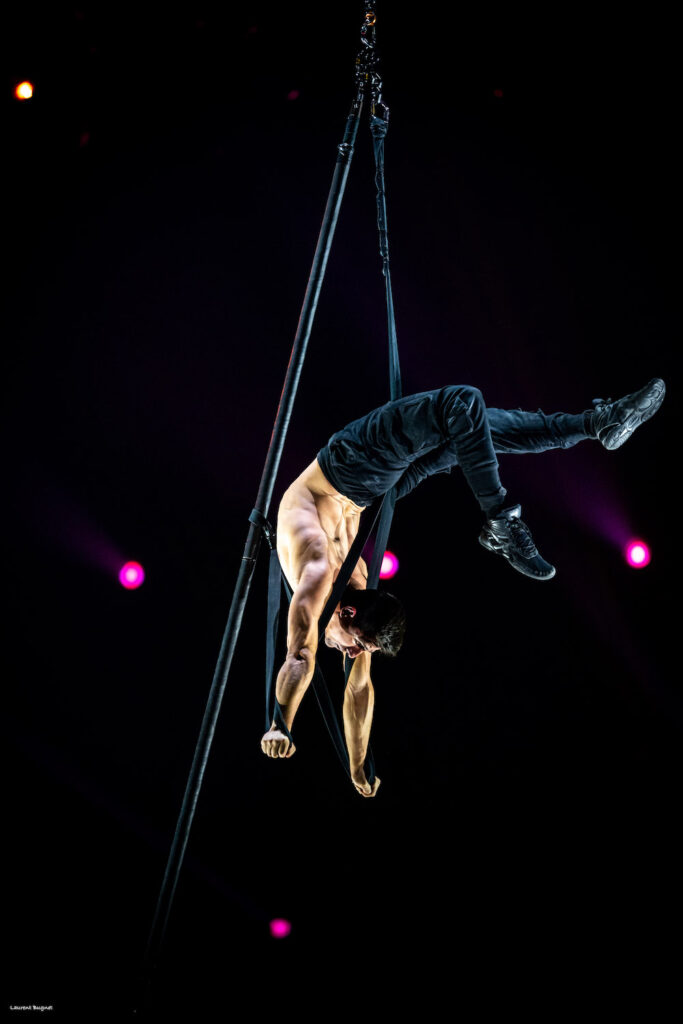

Silver medals went to the impressive handstands of Polina Makarova (Mexico) and to two acts of the more widespread aerial techniques of our time: Quentin Signori on straps (France), and the Ukranian twins Gemini, with their duo turn on the aerial pole. Variations and combinations of aerial techniques are a usual staple of the festival—this year it was also the case with Emanuel Garcia Nerox (Mexico), who combined straps with aerial pole, and the One Two One duo (Brazil), who offered a nice turn of aerial rope and hair suspension. Or the bronze-winning Spanish duo Gustavo and Nerea, with the elegant creation of a fixed trapeze catcher and proper tricks of the “aerial cradle” technique.

Two more bronze medals were awarded to an unusual variety of specialties: the eccentric tumbling duo Ma Mao (Brazil), formed at the Lido de Toulouse school, whose signature for decades has been always applying unexpected physical comedy to acrobatics; and the surprising sword manipulation act of Titos Tsai (Taiwan).

Several other special awards were presented, as usual, to reward the main strength of identity required to shine at this festival: elegant ways of playing with circus’ codes and techniques, disassembling them, and re-combining them with their own culture, with the universal acrobatic heritage, and with an artistic sensibility able to transgress the conceptual borders of circus itself.

After almost half a century, the butterfly of tomorrow’s circus is still working its magic tornado.

The other participating acts, not aforementioned, also includedTrio Tête-Bêche, acrobatics (NL-D); Agustín Rodríguez Beltrán, straps (Mexico); Cie Nicanor de Elia, juggling (Argentina, Brazil, Spain, France, Italy, Uruguay); Andy Jordan, juggler (Austria); Arthur Cadre, dance-contortion (France); Antoine Boissereau, silks (France); Carlo Cerato, juggling (Italy); Peng Chan, diabolos (Taiwan); FootStyle Freestyle football (France); Evgeny Kurkin, Chinese pole (USA); and Pei Pei, foot juggler (China). Each show also included, outside of the competition, the comedic « réprises » of Cie Soralino (France, Italy, Brazil).

The Jury was presided by Lucas Dragone, art.dir. of Dragone (Belgium), and had as members Nathalie Bondil, Museum at the Institut du Monde Arabe (France); Estelle Clareton, creat. dir., École Nationale de Cirque de Montréal (Canada); Péter Fekete, dir. Capital Circus, Budapest (Hungary); Valérie Fratellini, head of studies, Académie Fratellini (France); Kerol, artist, former Silver Medal (Spain); Pavel Kotov, Senior Director Casting and Artistic Management, Cirque du Soleil (Canada); Enkhtsetseg Lodoi, president Mongolian Contortion Association (Mongolia); Markus Pabst, art.dir. BASE Berlin (Germany); and Giulio Scatola, Casting and Performance dir., Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey (USA).

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!