An Interview With Shana Carroll, Member of the Order of Arts and Letters of Quebec

Shana Carroll’s name does not require an introduction for anyone who follows the development of the circus arts. When at the beginning of May, the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec (CALQ) announced that Carroll was among the luminaries to be inducted into the Ordre des arts et des lettres du Québec later that month, we in the global circus community all felt a sense of collective joy. The honor was a long time coming, and well-deserved.

The Ordre des arts et des lettres du Québec is awarded to artists, writers, teachers, managers, and patrons whose outstanding achievements have helped make the arts thrive in Québec … and beyond. Shortly after the announcement Carroll, who was born and raised in the US, stated in her thank-you post on Facebook that “… as I arrived in Quebec, in 1991, I finally felt I had permission to be an artist.”

Carroll’s move to Quebec, and the synergy between an abundant artistic mind and a welcoming and nurturing creative environment, gifted us with a boundary-pushing, fiercely visionary creator, who co-founded Montreal’s Les 7 Doigts de la Main (The 7 Fingers Collective), one of the circus companies that has changed the paradigm of how the circus arts are perceived within the performing arts. Without this move, we would probably lack today the unforgettable experiences of such iconic shows as the Drama Desk-nominated Traces, as well as Sequence 8, Le Murmure du Coquelicot, Passagers, Cuisine & Confessions, Duel Reality, and Psy, just to mention a few.

In addition to her work within the 7 Fingers, Carroll also created the circus show Queen of the Night at the Diamond Horseshoe in New York (a 2014 Drama Desk Award for Unique Theatrical Experience), co-designed the first segment of the Sochi Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony, and collaborated with Cirque du Soleil on multiple productions, such as Iris, Paramour, Crystal and Cirque’s 84th Annual Academy Awards performance.

Amid her busy schedule in the recently opened production Water For Elephants, I had a chance to ask Shana about her prestigious distinction, the state of the circus arts, and of course, this most recent project, which had its run at the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta between June 7th and July 9th.

Andrea Honis (AH): Congratulations on the prestigious distinction of becoming a member of the Order of Arts and Letters of Quebec! Do you consider this as some sort of culmination point of your career? How do you see this award in the trajectory of your career?

Shana Carroll (SC:) It’s honestly really overwhelming. I feel, if anything, it’s the trajectory of my relationship with the province of Quebec. Coming here in 1991… it really did feel it was a place of artistic “fertility,” and it transformed me with its encouragement and support for the artists it fosters. There is no way I would have had the courage to take the steps I did, and to believe in my own voice, if this place wasn’t such a healthy incubator. Culture like that starts from the top. Usually, as artists, we feel we need to fight the system! It’s just astonishing to be in a place where the “system” is on your side. Though artistic rebellion can bring on great work, work that is made with freedom and support just feels a lot saner :).

All of the inductees were recognized for work in their given field, and of course, mine was in circus arts. How many places in the world would award such an honour in the category of “circus arts”? How many places in the world would even dare to put the word “arts” next to the word “circus”? What this province has done for circus and its creative and cultural evolution is just phenomenal. Of course there’s the chicken and egg question, but I firmly believe that the various companies and creators and schools here that have influenced our form began first with this province that chose early on to support and accept circus as one of the high arts. Even when you think about what Cirque du Soleil has become, it all started with a pretty hefty grant in its infant years, from a province that said, “Hey yeah, why not, sounds cool!” Sorry—this sounds like a campaign for the province of Quebec! But I really can’t say enough how grateful I am for all it’s given me.

AH: Reflecting on your career path, what has been your most memorable junction or turning point?

SC: Haha, maybe I just answered that above! But instead, I’ll bullet point a few of them? Is that cheating?

1/ 1988, when I saw Sky de Sela practicing on fixed trapeze in the old Pickle Family Circus church on Potrero Hill. It was an instantaneous shift. It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen and at that moment, on a dime, I abandoned whatever life plans I had in order to be a trapeze artist. Head-first, no safety net, in every sense of the word. It’s the kind of fool-heartedness you are perhaps prone to at the age of 18, so I’m grateful I was that particular 18-year-old fool.

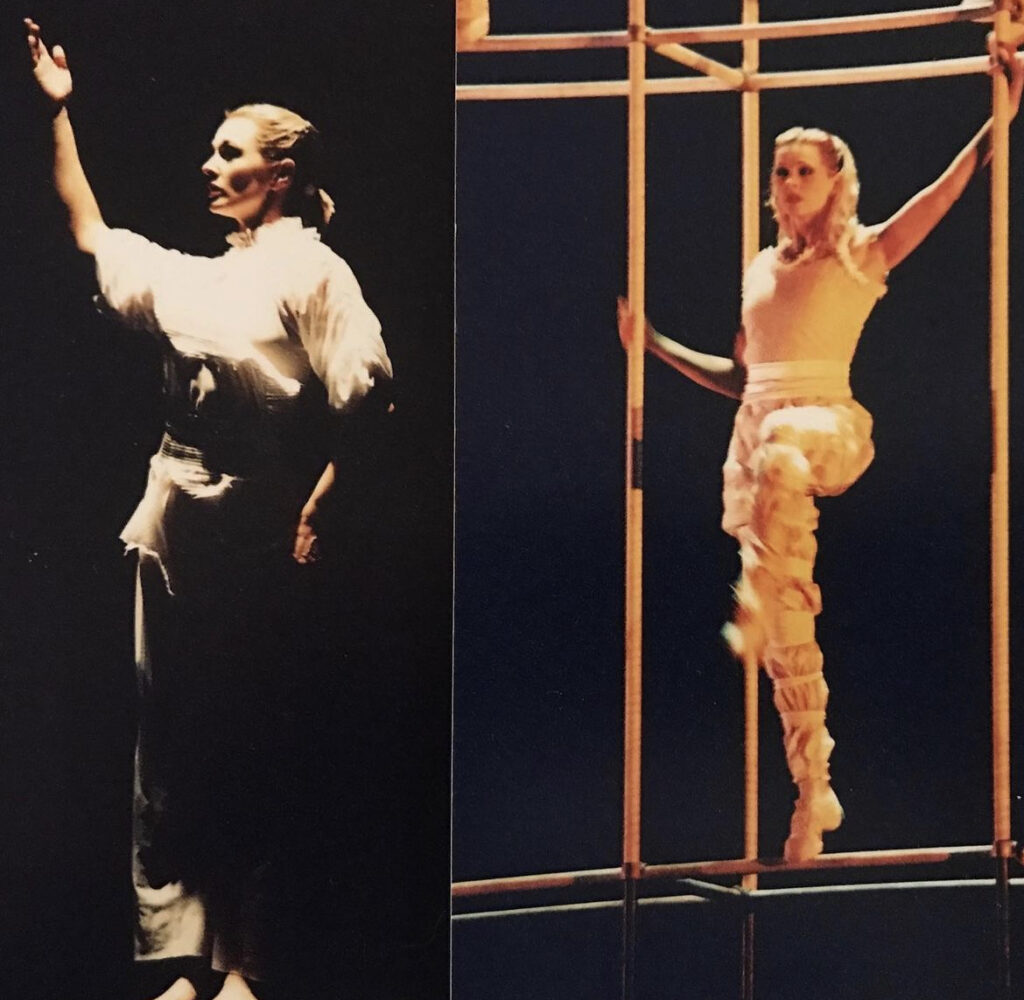

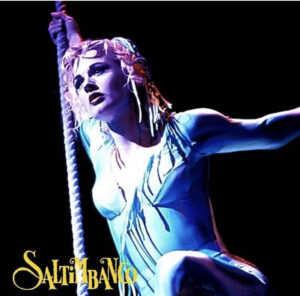

2/ Going to Montreal’s ENC in 1991. A bit of what I mentioned above: I felt genuinely nurtured, not just as a performer, but as a creator! My first end-of-year show was a supervised student-directed show where I took on choreography with another friend. It’s where I found my second passion. From that moment on, I tried to continue down these parallel paths of developing and performing as a trapeze artist, while doing anything I could in the meantime to continue choreographing. I’d ask fellow students if I could choreograph their acts. At Rosny, I asked the school itself if I could assistant direct. Later on with Saltimbanco, I was made dance captain and encouraged to sometimes re-choreograph a small section, or even create brand-new acts. And really it all started from that first year at ENC when I was 21! Being given space and encouragement and permission. It sounds kind of cheesy saying it now—like a plant just needing sunlight, water, and love–but it really was like that through my student and performing years: in every instance, I was really fortunate to continue to have sunlight, water, and love for all my creative endeavours.

3/ Number 3 is a funny one… I spent seven years with Saltimbanco. In my very last year (2001), I got pregnant, and had a whole plan of continuing to follow the tour, to maybe “graduate” into other roles within CdS, to stay within their care. Then I miscarried — it was a pretty traumatizing one—and at that point, I really didn’t understand the likelihood of miscarriage, and there were other medical complications. It was such a powerful turning point. I had already stopped doing my trapeze act; my replacement was on her way. It seemed so fundamentally wrong to go backwards into a role I had said goodbye to. Also, there was something about having peered over a wall into motherhood, and it was like I needed to continue over that wall, somehow. While still trying to get pregnant again, I knew I also needed to essentially “birth” something else. Or, more practically: my few months of mother-to-be-hood also made me realize the many doors I would possibly be closing once I had a child, the certain things that would be exponentially harder to achieve, and that maybe it was now or never to properly examine my life goals and dormant dreams, etc. So I left CdS and just went full-on blank page/clear horizons head-first into carving out my next creative chapter. I knew I wanted to start my own company; I knew I wanted to work with friends; I knew I wanted to direct/choreograph but still perform. One year later The 7 Fingers was founded. It’s hard to say from the final destination of it all if I would have wound my way here anyway. But I’ve long felt it really was that miscarriage that propelled me to take that huge leap and put my pent-up lost-motherhood feelings into creating a company. (P.S.: I finally had a child, seven years later! Seven is the magic number I guess 🙂

AH: When you started your career in this industry, the ecosystem, the infrastructure, and even the world around us looked rather different. What do you consider the biggest changes and challenges that performing arts have faced in the past 20+ years?

SC: Oof. Well, circus was a WAY more marginalized form. When I was a trapeze artist at Pickles, I knew maybe three other trapeze artists, who were all abroad somewhere. There was no internet, and other than a couple of great VHS tapes Gypsy showed me, no way of researching what else was out there. I gave tricks names that I made up; I played around on the trapeze; and every move I found, I thought I’d invented it! On the one hand, it definitely pushes creativity and a great sort of ownership of your work. On the other hand, the tools simply weren’t there, and it was a MUCH harder path. Even rigging-wise: we didn’t yet have the trapeze on pulleys, so it was always at full height! So part of learning trapeze took also the instant courage to do it high in the air; really such a different type of training. Haha, I sound like, “In my day, we walked uphill both ways in the snow…”

But it was just way tougher and took way more determination. Even at ENC, which was considered more established at the time: my first year the entire student body numbered, like, 25 students? There were five of us in my year. I was the only American. We were a tight-knit band of determined weirdos.

And yes, about it being marginalized… in the US particularly, there was still the “circus freak” stigma. I always had to put up armour—joining a conversation with a stranger, preparing myself to defend and educate and enlighten, and it was exhausting. I mean, that still exists to a certain extent, but the legitimacy and proliferation of circus skills has been mind-blowing. There are aerial schools in nearly every town now! People do it as a form of fitness or recreation!

But I do have mixed feelings about the mainstreaming of it all. It’s of course a net positive, and one of my missions in life is to get our circus tentacles out there and extend our reach into as many hearts and homes and minds as possible! But there was a sort of sacredness before—perhaps due to the fact it was such a DIFFICULT life choice, and to survive, you had to individuate (when training swinging trapeze at ENC with Andre Simard, his students wouldn’t even learn the same tricks! Each one of us had to have unique research), and so it’s harder for me now to see people all learning the same routines like in a yoga class :). Or to watch IG videos of a circus skill from someone who doesn’t know the fight or the history…

Believe me, I’m not a purist. But of course, there’s a different level of intensity and commitment when people gravitate towards it ‘cause it’s cool or popular or even glamorous, compared to those of us who had to go against the grain. So yes: the fact that circus is “more” mainstream fills my heart! And keeps me employed! But if I could have it both ways, I would love to still have the FIRE and devotion of the early marginalized days.

That said, we still have a long way to go to gain full-on artistic legitimacy. It blows my mind how STILL, an old friend of mine will come to see one of our shows and say how they had no idea this existed. “This” being more or less contemporary circus.

Also, we still fall into an uncomfortable (and sometimes genuinely dangerous) crack. I see this now as a creator: more and more other forms want circus elements in their shows or events, and yet still don’t understand what that involves, or how to support it, and are frequently shocked by rigging or cost or circus-specific needs. So often circus arts are squeezing themselves to fit into the structures and processes of other forms. So that still scares and frustrates me a little. Whereas when we were in our own circumscribed land, we provided our resources and made our rules, etc.

Again, don’t get me wrong!!! The cross-pollination of forms is what I live for! As a spectator and a creator. I would just love to be a little further down that learning curve, so I don’t make myself crazy at every collaboration, exhaustively repeating and explaining our “weird” (and critical!) needs.

AH: What is your future vision for the performing arts?

SC: Oh… I try not to think too much about that. In that, I’d rather follow my Spidey sense than “vision.” My Spidey sense and hope. I have hopes for the future of performing arts. And gut instincts for my own next steps, at each turn. But if I get too broad-lines vision-minded—if I examine trends and revenues and society—I get logical and cynical and fearful. But when I’m listening to my own gut instincts at each turn, then I have some agency in what direction we all might go.

And as for “hope”…

I HOPE our increasingly virtual, removed, online lives create an even greater need and desire for genuine human-generated awe and contact and presence and for shared heartbeat, sweat-flying-into-the-first-row experiences.

I HOPE hybrid forms will continue to merge and create mixed-media offspring that continue to defy category and expectation.

I HOPE acrobatics one day holds its place alongside ballet and opera—simultaneously prowess and storytelling, athletics and art.

I HOPE we have governments that recognize the arts as essential to humanity and society and education and mental health and politics and all that jazz—yes, imagine that 🙂

AH: You have just recently premiered Water For Elephants The Musical, where you worked as a co-choreographer and circus designer. Water For Elephants is not your first Broadway musical. [Shana acrobatic designed and choreographed Paramour, Cirque du Soleil’s Broadway musical, in 2016.] How does Water For Elephants, whose storyline is primarily known to audiences through the movie, differ from your previous Broadway experience, and what makes this production special for you?

SC: Now, just to compare the two right away: Paramour was a Cirque du Soleil-initiated project. The idea was to do CdS on Broadway, and in fact, to take the bones of our show Iris (2011/2012, at the former Kodak theatre in Hollywood—I was also the acrobatic designer/ choreographer for that) and give it a bit more story and a Broadway format. It was approached more like a jukebox musical: in a jukebox musical (like, say, Mamma Mia), the music exists already, was originally written for a different purpose, and is a given and imposed and the play-makers have to write and superimpose and wind a story around it. In a way, Paramour was similar, except that instead of having a pre-existing soundtrack, we had existing acrobatic content. That said, I actually changed all but two acts of the existing acro content, in a judgement call to better tell the story via different acts. But still, even the notion that there is a story woven around the acrobatics… it’s counter to everything Broadway is, which is pretty much the church of storytelling.I often compared the type of show Paramour was to an opera or ballet: a sometimes loose story that provides a context and motor, but mostly allows for dilated moments of prowess and beauty, musical or physical “excellence.” But that is not the Broadway model or standard, and trying to fit Paramour into such a model or standard was a very tough fit. I had a fantastic time creating the acro content—some of my favorite acts I’ve ever made! Including the genesis of “Hand to Trap,” which was conceived entirely because I was trying to imagine an acrobatic way to portray a love triangle.

Water For Elephants is completely the opposite, in the sense that, instead of the acrobatics being the main vehicle in Paramour, with the story being there to feature them, in Water For Elephants I’m 100% in service of the story. It often takes a great deal of restraint—peppering just the right amount of acrobatics to tell the story, convey the imagery, evoke the emotion, and sometimes ten seconds too much is enough to derail us from caring about our main characters, and we have to reel it in, hold back. It’s a very interesting process… as a circus performer, you are always being told to basically use every tool in your tool chest, to throw in every trick you know! I had to be SO sparing and judicious.

What was fun with Water For Elephants was that I got to start with the script nearly four years ago, and dream up what acro content would tell the story best. And then propose it to Jess (the director), and workshop it, and back and forth… it’s really what I love doing most: that sort of blank-page approach, but with a profound and solid story as a compass. I read the script and thought, “OK, here’s a scene where they’re putting up a tent; let’s see, maybe we can make that an acrobatic act” (anyone in the circus knows that putting up the tent is itself a show :)). We could mount a pole, juggle sledgehammers, throw around and jump ropes, etc. Honestly, there were so many possibilities, it could have been in its own hour-long show! But we needed to use just the“‘right” amount, pick and choose and cut and trim and carve…

Or in the dream sequence at the end, I thought through the events of the character’s life—his parents’ car crash, running for the train—and asked, how can we recreate that imagery with our language? It was tremendously fun. And working to figure out the horse puppet. That one was a magical collaboration. Jess had a vision and asked how I could put it to life circus-ly; we banged out a rough draft, then the puppet team came in, all of us Zoom-workshopping across borders during those pandemic years… In so many ways it was a dream project: so many elements I deeply love under the same roof, all working to tell one story.

As far as what makes it special for me… the entire story is about a guy who does a 180 from his life trajectory and jumps onto a circus train and finds a new family! One of my favorite songs [in the show], the chorus is, “I choose the nowhere on wheels, I choose the rattle of steal, I choose the circus, I choose the ride.” I tear up every single time. So, some details of elephants and spousal abuse and moonshine and imagined murder aside—practically autobiographical! But seriously: how can it not be special to me?

AH: Tell us about your experience working in a multidisciplinary creative environment as opposed to directing a circus show.

SC: It’s stimulating and educational and inspiring and HARD. I mean, let’s be honest, the simple fact of being used to being the director and picking and choosing what needs time and energy and a second draft, when and how I want to tweak, or to let things sit and marinate, or to blitz andfine-tune… all that is out of your hands, and it’s someone else’s compass you have to respond to. I often felt I had to put work up on the stage I didn’t find finished, because there were priorities elsewhere. I sometimes didn’t agree with certain choices and we’d need to debate :). My mind would get changed, or I’d change minds, but man, the energy in just that! In that respect, it’s not that different than the collective work I’m used to with the Fingers.It’s just the nature of these huge collaborations: we’re like a 5 headed beast lumbering slowly forward, consulting and discussing and exchanging at each step. Whereas when I’m directing alone, I just need to give it some thought while I’m washing the dishes. But it does mean we eventually lumber forward into a crazy unprecedented place no one individual could have dreamed up alone. So that’s for sure the beauty.

There were also definite learning-curve things on my part, too, about professional theatre. I did do theatre quite extensively in my early years, and even directed a few plays, so it wasn’t so much the different artistic form as it was the structures and systems and protocols and precedents. We’re pretty lawless in circus, and just use a lot of moment-to-moment common sense. But the professional theatre world is mind-bogglingly structured when you come from circus, and it took a lot of energy to navigate. For the acrobats, too!

I adored the mix of forms, though: listening to the singers, the orchestra. Discussing dramaturgy. The talent in that room! It is exponentially more stimulating than just being alone in my own creative mind. But yeah—harder, too :). Inevitably.

AH: At CircusTalk, one of our founding missions has always been that “We want to perform in a world where circus is recognized as a practice as well as an art form, and has become an important driver of innovation and re-imagination within the performing arts.” How do you see the circus arts being treated in this theatrical environment?

SC: Well, for sure there’s been a huge step in that direction. There was so much reverence for the circus arts from the whole team, the whole rest of the company, and acknowledgment of it as being an art form and essential to the storytelling. And I witnessed it as some of the actors or collaborators were in fact discovering this for the first time. So I very much feel that all of what you wrote above was definitely recognized, and many found that knowledge eye-opening.

That said, I still felt like it was the tiniest fraction of circus’ capabilities in that respect— and even for me, for my own work—the tiniest fraction of the depth and innovation and storytelling I feel I’ve been able to do in my own shows. Which, yes, of course! It’s a musical, and circus is not the principle voice! But I think we haven’t yet tapped into its true capacity to tell deep stories in that mainstream American theatre environment. But it’s coming 😉

AH: How do you see circus performers being ready and equipped to perform and collaborate in the wider multidisciplinary, theatrical environment? Does their circus school education prepare them for this rapidly expanding space within the performing arts?

SC: Yes and no. I think circus artists are wonderfully equipped to be creators and innovators and able to interpret and, in turn, dream such a wide range of expressions and stories within their disciplines. They are not trained to be soldiers, but thinking/feeling creators. And that’s huge.

However—as the forms are merging more and more—it feels time that schools broaden the curriculum to include more straight theatre, vocal work, music… these things are all touched on, but fractionally. I use text a lot in my shows, and for the most part, circus school graduates come to me having never been taught to speak on stage, and don’t have even the most basic skills of projection and diction, not to mention motivation/beats, etc.—Theatre 101 stuff. Maybe this is my own preoccupation, because I’m interested in circus-theatre fusion. But I feel like the dance component and training are heavily emphasized (and, yay! Also what I love), while classic theatre, not so much.

I’d even add — more and more we do ensemble shows. Usually, we highlight everyone’s main discipline, but we’re mostly interested in how they can be part of an acrobatic ensemble. I still feel schools focus too much on students having to create one act that they leave with and sell and tour etc. Which is also important but there’s a balance to be found there too. There’s a weird notion of “specialists vs generalists.” Ideally, everyone’s a specialist and a generalist.

And as a very last, more practical note: learn rigging. For real. Don’t go out into the world not understanding the mechanics of the thing that keeps you alive. Especially if you’re venturing into non-circus-specific environments.

.

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!