In 2023, Monte-Carlo Festival Shows Many Shades of Tigers and Somersaults

From the stands of the 45th Monte-Carlo International Circus Festival (January 20-29, 2023), Raffaele De Ritis reports to us on the triumphs and the art in its display and investigates the event’s fascinating, fairy-tale history.

A crowd of 4,000 is sitting under the big top, eyes in the air, but Sabrina stands discreetly by one of the staircases in the audience. Most of the crowd there has come in from every corner of the world. For the time in therôles of anonymous audience members, they are clowns, retired acrobats, producers, writers, manufacturers of tents, poster printers. Some of them have made the trip from as far as Chili, Ghana, and Australia; they all know each other. Meanwhile, Sabrina has tears in her eyes. She just witnessed her kid, Maicol, missing a quadruple somersault in public.

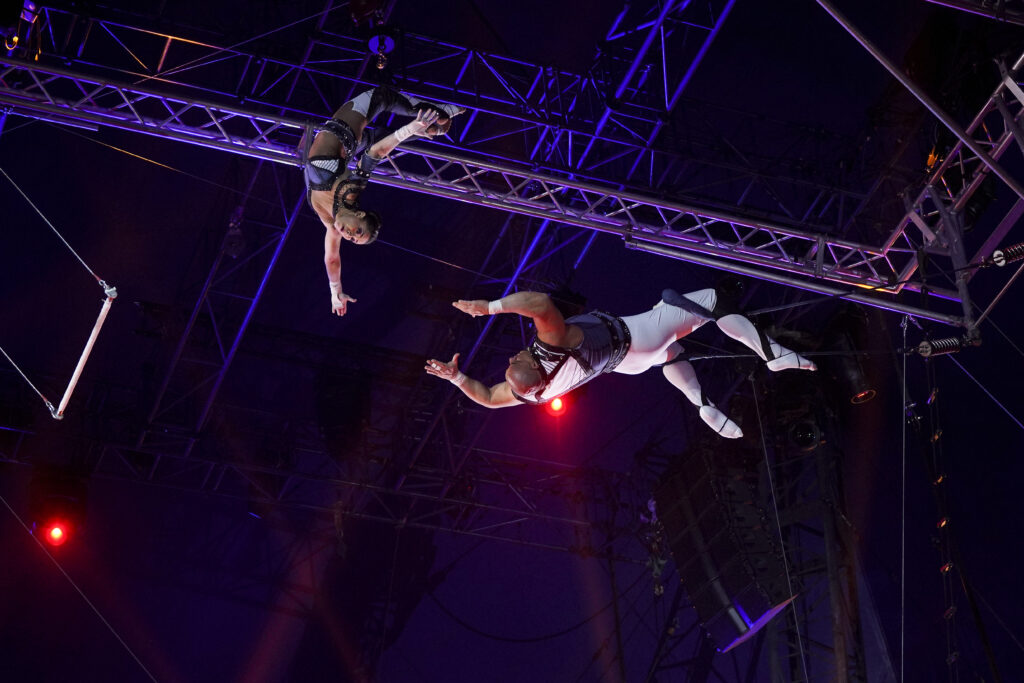

In 2013, in a tiny ancient Italian village on top of a hill, when just 13 years old, Maicol Martini became the youngest flyer ever on Earth (and the first European) to achieve a “quad,” the Holy Grail of circus history. This feat gained him an entry in the Guinness Book of World Records. But, to him, tonight’s challenge is even more significant than the Guinness Book itself. His dream is to impress the circus community and, hopefully, win a Gold Clown: the award recognized for 45 years as the circus world’s own Oscar. He tries a second time, his hands touching, for an instant, the wrists of his catcher, only to slip again and fall into the net. Sabrina cries.

Sabrina dell’Acqua comes from a very old Italian circus dynasty, as does her husband Darix Martini; they made it to Monaco all the way from Southern Italy. For five generations their families were devoted to sawdust and spangles, and now they face an impossible dream.

Maicol falls once more into the net. If, under the lights, he is clever in hiding his desperation, the same is not so for Sabrina, still standing in the audience. The ringmaster, Petit Gougou, extends his shining silk top hat toward the jury, then the orchestra; a third, last attempt is accorded. The silence is only broken by the slight creaking of trapezes, the discrete drumroll, and some loud “hup!” sounds from the catcher.

Maicol’s preparatory swing is this time visibly larger in the space, his body’s rotation higher. The clap of touching hands blooms now into a tiny puff of white powder. Done. It’s done.

While the crowd rises, and cheers, deafeningly, all pushed in a split second by the same force, Michael swings back and turns a mid-air pirouette, triumphantly reaching the safe platform. A small group in the audience jumps around, hugging each other. These are the greatest flyers in the world, some of them retired, conveyed there from Mexico, the US, or England to admire Maicol. Few of them have achieved the quad in the past; others have pursued it all their lives without achieving it, not less than Ahab with his Moby Dick; but they are far from being jealous now. This is shared mythology. Meanwhile, from the staircase shadows, Sabrina’s tears turn in a fraction of time from ones of sorrow to joy.

This, for circus folks, is Monte-Carlo, for decades considered to be the unparalleled greatest circus show on Earth.

The cradle of circus competitions : a fascinating history

Maicol’s group, the Flying Martinis—a beautiful troupe from Italy (with some Brazilian members)—January was awarded a Silver Clown at the 45th Festival International du Cirque de Monte-Carlo. Common belief (as these awards always bring about countless speculations, speculation being among show folk’s major hobbies) was that the jury didn’t consider them for a Gold, supposedly because of Maicol’s too-many attempts for the quadruple. How important is a technical “mistake” in an art form competition? Is it a failure, valued as a definite imperfection? Or can the emotional factor relieve this judgment? And how much can a trapeze artist compete against a tiger trainer or a clown? These are some of the structural compromises of circus competitions: but at the same time, they happily endure as the accepted standards that the circus community has shared for almost half a century in dozens of festivals. And Monte-Carlo was the cradle of the very concept of modern circus confrontation.

Whereas the word “festival” had been used mostly as a promotional title for circus shows and galas in the century prior, it was only around the mid-1950s that some attempts were made to award titles at these events. One pioneer of this was the Spanish impresario Juan Carcellé (1895-1978), whose cycle of winter circus galas, titled “El Festival Mundial del Circo,” terminated with the assignment of some prizes, and was followed in the 60s by similar attempts in France or Italy. “Festival” was a magical word meant to meet the exotic appetite of European audiences, in a world where a safe antidote to the Iron Curtain’s effects was found in the idea of “cultural exchange.”

During this time, the young Prince Rainier III of Monaco (1923-2005, crowned in 1949) devoted much of his spare time to a consuming passion: the circus. Whatever country of the world he was visiting, he knew what big top was playing where, as well as every single artist or animal performing in it. Even remote Sarasota, Florida’s show folks town, had no secrets to him. In the mid-60s, his stamp-sized country’s tourism- and gambling-based economy was declining. Russian archidukes were a past souvenir for the faded glories of local casinos. Legendary Greek millionaire Aristotle “Ari” Onassis foresaw an exit for him and started to invest in Monaco’s development, stimulating American tourism. His intuition was topped off by the marriage of Rainier to movie star Grace Kelly.Monte Carlo thus became a sort of Vegas-sur-mer, the world capital of jet-setting. But Rainier wanted to attract gamblers and bathers there with the opposite of “Sin City”: he developed sporting events, opera and ballet seasons, museums, awards. His passion, the circus, was barely considered culture at the time. By the early 70s, he seriously considered becoming the first chief of state in the Western world to definitively dignify the form.

And so he called on Doctor Alain Frére, the world guru of circus fans and collectors, to develop an unprecedented project: inviting international performers to a competition“to promote the circus around the world” (as the first official press release stated, borrowing the Prince’s own words). René Croesi, director of the Monte-Carlo Philharmonic, was their choice as manager. Circus Bouglione from France lent its big top and some acts—but what about other performers? The best European talents at the time tended to take contracts in the US. Quality European circuses were a fading tribe. Nearby Italian circus dynasties helped to bring in as many artists as possible; others came from Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria. A jury was formed with a group of distinguished writers, actors, and cultural personalities. An award, the Gold Clown, was created as a career achievement trophy, with a Silver to be awarded to competing acts.

On December 26, 1974, movie stars and crowned heads of Europe and the Middle East were seated under the circus big top for the first Monte-Carlo Festival. From then on, the circus arts started its modern legitimization in a slow domino effect. A few years later, the French government, as had Italy’s before them, recognized the circus arts within the Ministry of Culture.

In the following editions, the “Americanization” strategy of Monaco also influenced the festival’s growth. A double agreement with CBS-TV and the Ringling Bros. Circus ensured its strongest programs; broadcasting it in 26 countries (with Telly Savalas—yes, Kojak—and Lynda Carter, a.k.a. “Wonder Woman,” as hosts) embedded the festival in the worldwide collective imagination. For years, the jury panels were composed of names from the jet set Rolodex of the royal couple, such as Cary Grant, Sean Connery, and the finest writers and movie stars from France or Italy.

Soon the Soviet Union, noting the festival’s prestige (and the American grip on the event), started to release their performers to compete and grant the courtesy of their own jury members. In a thrilling, sequined variation of the Cold War, the festival turned from a celebratory rendezvous into a real circus Olympics. If in 1976 the iconic star of the American circus, daredevil Elvin Bale, triumphed over the Russian acrobats, then two years later, Mexican trapeze legend Tito Gaona won ex-aequo with a Soviet acrobatic combination of men and bears. The juries soon became solely composed of circus directors; and, by 2002, a Bronze Clown had joined the Gold and Silver. The audience’s affection, and the TV’s fidelity, also resulted in the Festival turning into a profitable business.

By 1989, the Chapiteau de Fonvieille, a permanent big top construction, had replaced the pioneering structures of the Togni family. Prince Rainier never stopped overseeing every single detail of casting and organization until his passing in 2005. Today, his younger daughter Stephanie presides over the Festival, with its artistic direction assured by Urs Pilz (a Swiss gentleman, circus expert, and festival veteran) and Dr. Alain Frére still acting as advisor.

In more recent decades, the great Eastern troupes have dominated the Festival: China, Russia, Ukraine, North Korea, Mongolia. They inspired and challenged, with their classy acrobatic technique and with a theatricality that Western circus seemed to have lost. However, these acrobatic excellences had to share the podium with still very solid “schools”: the European equestrian tradition; the Italian tamers and clowns; and the South American trapeze artists. And the festival, while a quintessential part of the classic circus, has not remained alien to innovations: it was among the first events to propagate both the artists of Cirque du Soleil as well as the elaborate post-Soviet and Ukrainian choreographic research.

A somersault has multiple faces: the 45th edition

In 2022, the map of post-COVID circus festivals has a common element: the absence of China (due to COVID) and Russia (due to current events). For decades, they shaped programs and podiums, providing, as could no one else, large, spectacular troupes that performed on the ground, in the air, or on horseback. The shape itself of today’s circus expression is unimaginable without those cultures. As a result, this year’s Monte-Carlo program seemed almost to revert to the early years, when Western acts dominated the festival, save for the strong participation of Ukranian talents.

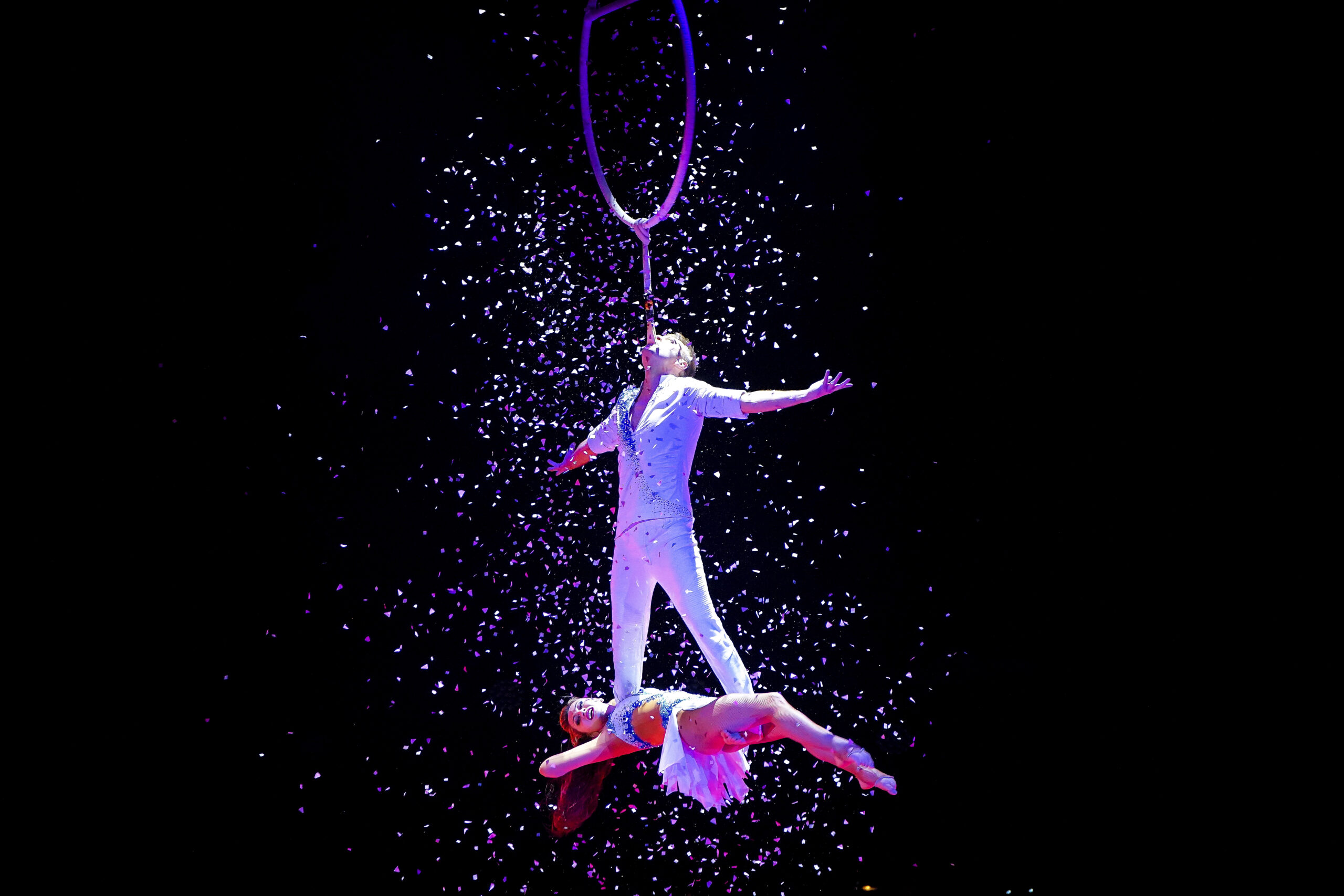

The only big Eastern acrobatic ensemble came from Mongolia, albeit staged by brilliant Russianenfant prodige Dmitry Chernov: “Mistery of Gentlemen” is a sophisticated, bizarre modernist turn on fetishized British hunting imagery with, yes, Mongolian performers. It was, from an aesthetic point of view, one of the most interesting acts competing; but the summit of artful refinement was Ukrainian contortionist Victoria Dziuba, winning a Silver Clown. A similarly polished Ukrainian act, the aerial duo Secret of My Soul, received a Silver too.

From Kiev also came the ubiquitous Bingo Circus-Theatre Ensemble. This company has generated a franchise for mainstream world circus industry leaders (e.g. Krone, Knie, Vazquez), providing both a corps-de-danse and acrobatic tableaux. If their hand-clapping, ass-shaking disco style is closer to cruise/resort entertainment than to actual circus choreographic research, their beauty, energy, lively charm and doubtless acrobatic gifts make them appropriate for the world’s most sparkling openings and finales of Monte-Carlo (and earned a Bronze Clown for them, too).

From Kiev also came the ubiquitous Bingo Circus-Theatre Ensemble. This company has generated a franchise for mainstream world circus industry leaders (e.g. Krone, Knie, Vazquez), providing both a corps-de-danse and acrobatic tableaux. If their hand-clapping, ass-shaking disco style is closer to cruise/resort entertainment than to actual circus choreographic research, their beauty, energy, lively charm and doubtless acrobatic gifts make them appropriate for the world’s most sparkling openings and finales of Monte-Carlo (and earned a Bronze Clown for them, too).

Speaking of mainstream aesthetics, this edition distinguished itself for the rare case of presenting a single Gold Clown: it was awarded to German acrobat René Casselly, for the novelty of his acro-dancing/equestrianpas de trois alongside sister Marylou and partner Quincy Azzario. René is considered by many the greatest living circus performer of his generation. As bold as that statement can seem, it is not so far from reality. In the last decade, he has shaped his acrobatic gifts in never-before-seen works with horses and elephants, and then successfully transferred his talent to competitive TV showsin his native Germany, Ninja Warrior and Let’s Dance. Besides ranking René as a celebrity, this experience has refreshed his circus art. His new act, conceived as a sort of disco-dance piece with a retro charm and a syncopated “The Phantom of the Opera” as its soundtrack choice, is a polished anthology of acrobatic rarities, balancing absolute technical excellence with a smooth, easygoing presentation. The piece includes at least two tricks never witnessed in circus history: a three-high balance on two horses and a double somersault on horseback.

Two more Silver Clowns came from Italy, both of them for specialists deserving Gold. One was the aforementioned Flying Martini troupe; the other was the ten-tiger group led by Bruno Togni. Bruno comes from true circus aristocracy lineage: his six-generation family is an iconic staple of Italian culture. His father, superstar animal trainer Flavio Togni, is the most awarded artist in the Monte-Carlo Festival’s history; his mom, Adela, is the daughter of two former American circus legends, wire acrobat Manolo dos Santos and trapeze star Galla Shawn. Young Bruno has spent half of his lifetime breeding ten magnificent tigers in different shades and colours (6 Bengals, 2 white, and 2 “golden tabbies”) and training them in never-before-accomplished jumps and tricks. Here he is also a composer. This act is a sequence of complex images wherein the elegant trainer discreetly stays somehow outside of the picture, like a conductor at the service of his music. Bruno’s work calls to mind the graceful minimalism and calm of legendary tiger trainer Gilbert Houcke.

Also from Italy came the liberty horse act of Alex Giona, an outsider to the circus world. In this poetic creation, conceived by director Antonio Giarola, the absence of saddles and harnesses is emphasized by Alex being barefoot in a white top hat and tuxedo (earning a Silver too). On the opposite side, a final Silver went to the high-adrenaline team of Mustafa Danguir (Morocco) with their two acts, a double Wheel of Death—including simultaneous tricks and a double somersault—and a version of the iconic seven-man pyramid on high- wire.

Also from Italy came the liberty horse act of Alex Giona, an outsider to the circus world. In this poetic creation, conceived by director Antonio Giarola, the absence of saddles and harnesses is emphasized by Alex being barefoot in a white top hat and tuxedo (earning a Silver too). On the opposite side, a final Silver went to the high-adrenaline team of Mustafa Danguir (Morocco) with their two acts, a double Wheel of Death—including simultaneous tricks and a double somersault—and a version of the iconic seven-man pyramid on high- wire.

Besides the aforementioned Bronze Clown, two other similar awards were presented: one to the parrot liberty act of Elisa Cussadiè (Italy), and the other to the thrilling Las Vegas-basedAmerica’s Got Talent favourite, the Deadly Games duo, for their knife-throwing act.

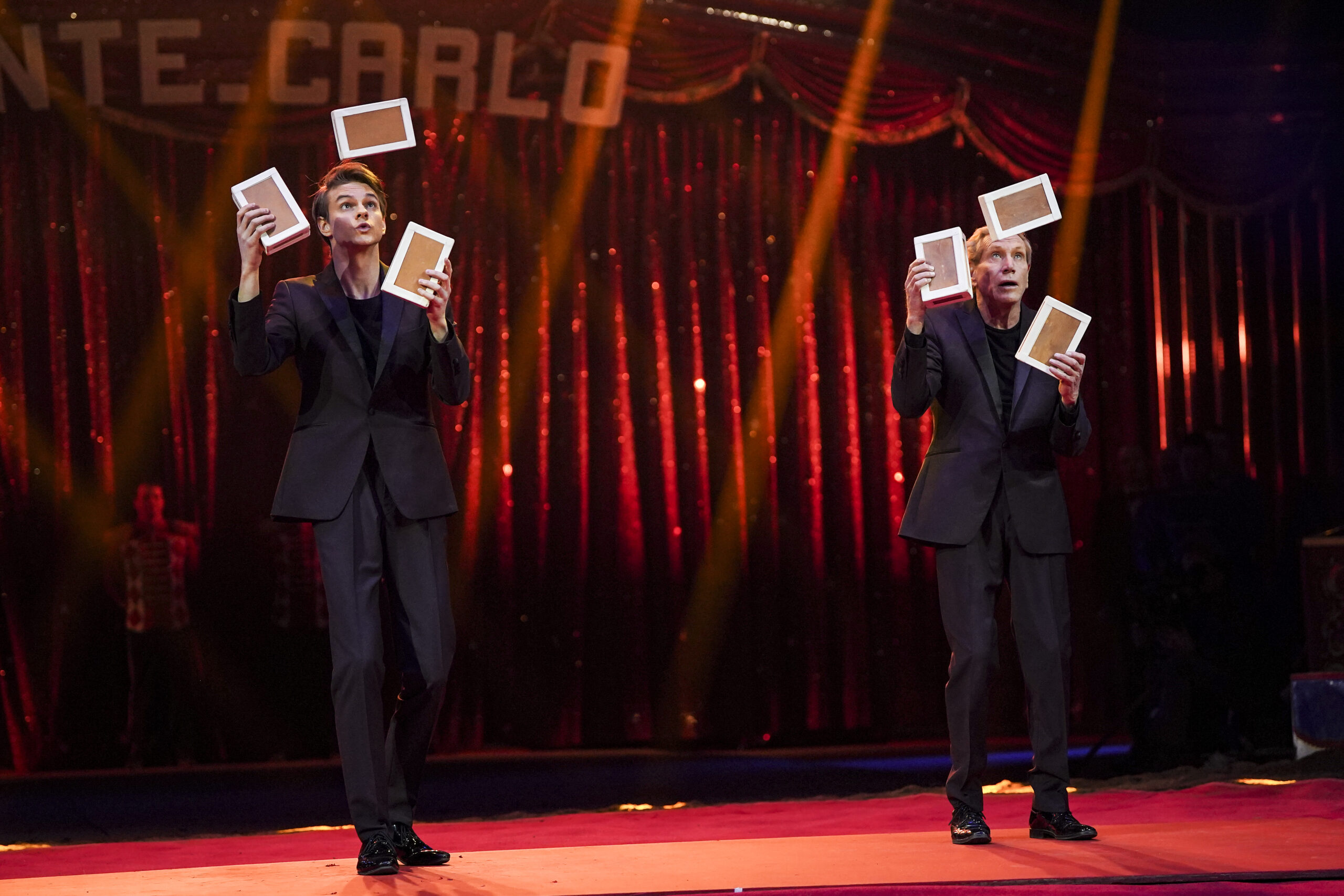

Other remarkable moments included the double juggling act of living legend Kris Kremo with his son Harrison; the spectacular large-scale illusions of Peter Marvey; the record-breaking unicycle heights of Wesley Williams; the brilliant Kenyan acrobats the Black Blues Brothers; and the sophisticated hand-voltige duo Dust in the Wind from Cuba.

Quality clowning was assured throughout by Ukraine’s Equivokee trio and the Italian artist Lorenzo Carnevale. Lorenzo brilliantly revived the archaic archetype of “l’auguste de soirée”: the hard, humble worker who fills the moments of technical ring work between the acts with comedy.

This Monte-Carlo Festival also included the 10th edition of the New Generation competition, generally held separately, which was composed of four acts—all female, with three of them coming from Ukraine. The Junior d’Or gold award went to wire acrobat Ameli Bilik; the silvers to Vladislava Naraieva (handstand) and Sofiia Hrechko (contortion). The jury panel too had a fair balance of both sexes and representatives from many continents, made up of circus directors and producers like Sosina Wogayehu (Ethiopia), Odette Bouglione (France), Luisa Raluy (Spain), Antonio Buccioni (Italy), Michel Rios (Morocco/France), and Aldo Vazquez (Mexico/the US).

A few weeks after the festival, Maicol, Sabrina and Darix Martini invited the various international prize winners of the festival to their circus in Sicily for a big party in the ring. They all seemed conscious of one thing: that, after 45 years, receiving an award at Monte-Carlo means not only the door to a brilliant career, but a passport into history.

Photos are courtesy of Centre de Presse de la Principauté de Monaco

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!