Deadlift Part 1: Let’s Talk About Deadlifts

Deadlifting, while being a fundamental exercise for strengthening the body, gets a bad rap. For my powerlifters, Olympic lifters, and Crossfit athletes, deadlifting is a usual and important part of training. But for my people who don’t regularly weight train, or my artistic athletes living a life of body weight conditioning all day every day, the deadlift often remains an elusive enigma of an exercise. So let’s break it down, what is a deadlift, why does it get a bad reputation, and how can we incorporate it into training to benefit the artistic athlete?

What is the Deadlift?

“Deadlift” is just a fancy name for a hip hinge, i.e. one of our bodies’ basic movement patterns of bending and extending at the hip. Reaching down to pick up groceries, that’s a hip hinge; bending to pick up that heavy amazon package and bring it into your house, that’s a hip hinge; rearranging furniture in your work-from-home space, you probably hip hinged!!

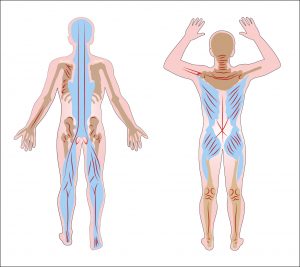

While there are tons of variations on a deadlift that you can train in the gym, the ultimate goal of each of them is strengthening the body’s posterior chain i.e. lats, low back, glutes, hamstrings, and calves for this hinging/ hip extension pattern.

If this is such an important and versatile exercise, why does it have a bad reputation?

There are a couple of main factors to consider here:

Firstly, it is true that if done improperly the deadlift can be a harmful exercise. We’ll go over the details of the mechanical dos and don’ts of a deadlift shortly, but for this point, we cannot deny that deadlifting with poor technique, inappropriate loading, and/or inadequate warm-up, can lead to injury. But, this is true of any exercise and of many sport-specific skills!

Injuries from poor deadlifting technique are often disc bulges, sprains of the joints of the spine and sacroiliac joint, and/or hamstring strains. With deadlifting (and other heavy lifting, but that’s for another day), it is thought as a matter of when, not a matter of if, an injury will happen, however, research has consistently shown that injuries occurring from lifting are almost always due to improper loading or technique, not due inherently to the movement itself.

Second, oftentimes, when someone is experiencing back pain, they are instructed by their medical providers not to lift any heavy weights (e.g. nothing more than ten pounds), and to avoid bending, but often are not given instruction or guidance on how to return to lifting weight or on proper movement patterns to maximize movement efficiency and decrease the risk of re-injury.

While this strategy decreases the risk of aggravating whatever may be causing a person’s pain, and is potentially transiently beneficial if that person’s back is in a current state of pain or inflammation, this strategy is flawed in that it is difficult to get through life without ever having to lift significant weight or to bend. Think about your grocery bags, backpack, soup pot, child, pet, furniture, all your new quarantine house plants… This strategy can leave a person with a fear of movement, and specifically with fear of lifting weight, and does little to correct the patterns that may have caused the pain in the first place.

Rehab Professionals, Do Better!

When taught by a qualified individual, and performed with correct form and appropriate progressive overload, the deadlift has actually been consistently shown to be effective in decreasing pain and disability scores in individuals with low back pain!

This happens by desensitizing the body to hinging (i.e. teaching the body that this is a safe movement, preventing excessive muscle tension and fear when its performed), strengthening the muscles of the core and back, and providing a safe technique for performing acts of daily living that require hinging at the hips. For athletes, deadlifting interventions have been shown to increase certain performance markers such as vertical jump height and lower body power output. From a rehab perspective, the coordinated co-contraction of the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius muscles makes it a great exercise to incorporate into a return to sport program as it reteaches the lower limb how to function as a unit.

We know that without proper preparation any specific skill can be dangerous if not performed properly. While it is true that deadlifting can be dangerous if done INCORRECTLY, either in technique or in loading, the same can be true of almost ANY exercise or sport. Gymnasts complete drill after drill to prep their body for the specific movements of their sport, and ballet dancers are evaluated prior to being allowed to start wearing pointe shoes; it should be no different when learning to deadlift. It is the responsibility of the coach or trainer to make sure the athlete learns to perform the movement correctly, and to add and progress load appropriately.

What’s The Dangerous Bit? How do we do it properly?

The key to a safe deadlift is core bracing to limit motion at the spine during the lift, and letting the hamstrings and glutes be the main drivers of the movement.

The way our spine is built, its structures become more vulnerable as we move into deeper ranges of flexion (bending forward, think piking) or extension (think bridging and backbends). In a deadlift, if we are using a load that is too heavy for our body to handle, and we are unable to maintain a proper core brace and stable spine, this can result in excessive flexion or extension at the spine during the motion, resulting in more force being placed on the spine itself while in a vulnerable position, and leading to injury.

Maintaining the position of the spine (even if we start in and stay in flexion like you may see some high-level powerlifters do) protects the structures from having to handle more load than they are conditioned for, and allows the muscles of the posterior chain to control our force and drive our motion.

Okay, So How Do We Do It Properly?

Let’s go over how to do a Romanian deadlift, a variation in which we start the exercise from a standing position, rather than a bent-over position.

First off, with my legs hip-width apart and knees soft, I’m going to brace my core, and set my shoulders down and back, making sure I am ready to stabilize my spine and control the weight during the motion

Then, I’m going to bend forwards at the hips, pushing them back behind me. Here my knees can bend to allow me to drop my chest down, and note that I keep the weight close to my body by maintaining engagement in my lats.

I keep my spine in the same position throughout the motion, and while I am flexible and can make it all the way to the floor, someone else may need to bend their knees more or less to get as far based on their specific mobility. It may be helpful to place a low platform between and behind the legs to act as a reference for where to move the weight to.

Feeling my hamstrings and glutes working, I push my hips forward to return to the starting position.

This is often where one can end up changing the position of their spine to a rounded or over-extended position. Keep that weight in close to the body and focus on maintaining your core brace, and engaging through your glutes and hamstrings.

All together now:

How can adding deadlifts into the artistic athlete’s strength program be beneficial?

Deadlifts are one of the best exercises for developing strength and power in the posterior chain (i.e. the lower back, glutes, and hamstrings), as well as proper core bracing during movement. Compared with exercises that focus on working just one of these muscles at a time, deadlifts, and their variations, get these muscles to activate together, and coordinate the movement together, which is more specific to how we move during sports and everyday life.

The strength and power that we can develop with deadlifting as part of an adjunct strength training program can translate directly into so many different aspects of artistic sports and activities. Consider jumps used in dance, gymnastics, figure skating, and cheerleading: barbell deadlifts have been shown to improve vertical jump performance and the rate of muscular force production. For acrobatic gymnastic bases, and hand to hand porters/bases, a deadlift, and more specific deadlift variations, exactly mimics the motion of movements such as pitching, cannonballs, and whip-ups/ drag-ups.

If you are starting to add a lifting day into your or your athletes’ strength training regimen, consider adding deadlifts into your routine. If you are not yet incorporating a lifting day into your training, read this article about the benefits of strength training for the artistic athlete, and then add a deadlifting variation into your usual conditioning set.

Want to reap the benefits of strength training for your athletes? Message me here.

References: Vecchio LD, Daewoud H, Green S. The health and performance benefits of the squat, deadlift, and bench press. MOJ Yoga Physical Ther. 2018;3(2):40‒47. DOI: 10.15406/mojypt.2018.03.00042 Tataryn, N., Simas, V., Catterall, T., Furness, J., & Keogh, J. (2021). Posterior-Chain Resistance Training Compared to General Exercise and Walking Programmes for the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports medicine - open, 7(1), 17. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. (2016). United Kingdom: Human Kinetics. Strength and Conditioning: Biological Principles and Practical Applications. (2011). Germany: Wiley. Sands, William & Mcneal, Jeni & Jemni, Monèm & Delong, T.H.. (2000). Should female gymnasts lift weights?. SportScience. 4. sportsci.org/jour/0003/was.html. Dowse, R. A., McGuigan, M. R., & Harrison, C. (2020). Effects of a Resistance Training Intervention on Strength, Power, and Performance in Adolescent Dancers. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 34(12), 3446–3453. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002288 This article was originally published at BENDDONTBREAK. .

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!