Circus as a Healing Art: What Polyvagal Theory Teaches Us About Why Circus Works

If you’re involved in the circus world, you’ve likely heard people talk about the healing power of circus, whether they’re casually joking about circus being “their therapy,” or reflecting on the transformative impact they’ve seen circus have on their students in a social circus setting.

This article is the first installment in a series that explores simplified interpersonal neurobiology that gives us a concrete way of understanding why circus works.

Autonomic Nervous System Basics

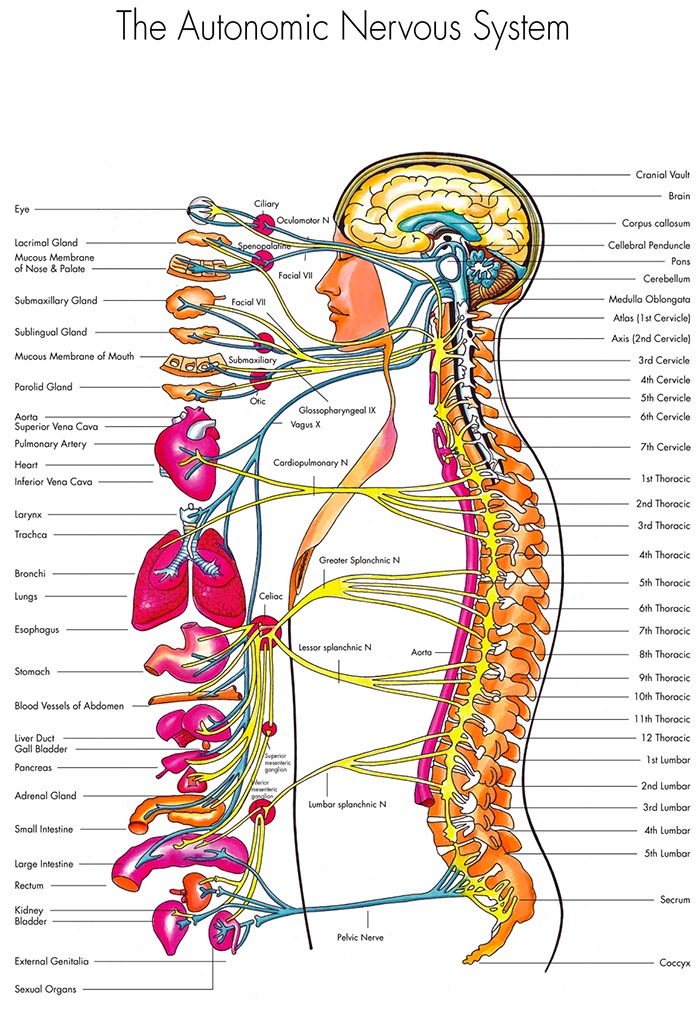

Our bodies carry out many functions (heart rate, breathing, digestion) without us having to mindfully cue them to occur. These functions are regulated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which serves as a “control center” for many of the automatic functions of our body.

Just like our heart beats on its own, without needing our mindful instruction, there are other systems that operate below the realm of conscious thought that impact the way we process and respond to the world as we encounter it. Stephen Porges, MD, coined the term Neuroception to describe when our nervous system detects and responds to cues before we have cognitive awareness of them. (A)

To understand Neuroception, imagine a time that you were startled. Your body likely responded physically before your cognition (thoughts) caught up. You didn’t have to tell your body to tense up, or to change your breath – your body did it automatically.

These types of responses happen all the time (sometimes more subtly, sometimes more intensely), and our autonomic nervous system is constantly learning to toggle our response system based on what we encounter and how things unfold. This part of our brain learns to manage risk, keep us safe, and create patterns of connection by changing our physiological state. (B) Neuroception is ultimately driven by a biological drive to survive.

In simple language, this means that our autonomic nervous system impacts the way that our body and brain responds to our experiences. In turn, this impacts our feelings, how we connect with others (or don’t), and our general state of being (do we feel shut down? social? safe? ready to fight or flee?)

Understanding more about what is happening “behind the scenes” in our body unlocks a new understanding of the way we move through the world. As noted by Bloch-Atefi and Smith (2014) “Our navigation of the world is inherently a mind-body experience,” and the more that we can understand the nervous system, the more we’ll understand the story– and impact –of this connection.

The Polyvagal Theory (PVT) will help us further explain a slice of nervous system theory, and what this has to do with circus.

Polyvagal Theory Basics

PVT can trace its roots back to some of Porges’ early work in 1969 with heart rate variability and a question about how the tone of the vagus nerve could be a marker of resilience and risk for infants. (A) In 1994, after many years of exploration, he presented the Polyvagal theory, which we’ll dive lightly into today.

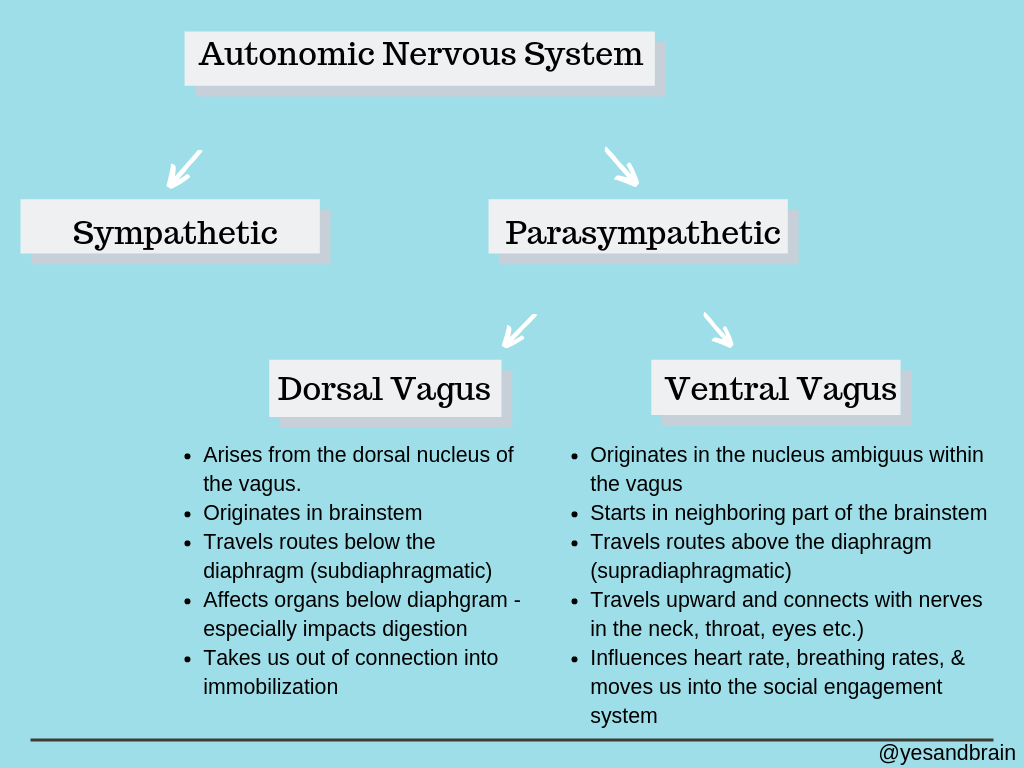

You’ve probably heard that we have two branches in our nervous system: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic. The job of the sympathetic nervous system is to energize us to take action (fight/flight) in times of need by increasing our blood pressure/heart rate etc., and putting unnecessary functions (like the digestive system) on hold. The parasympathetic system was said to work in opposition of this to return the body to homeostasis when the perceived threat had passed.

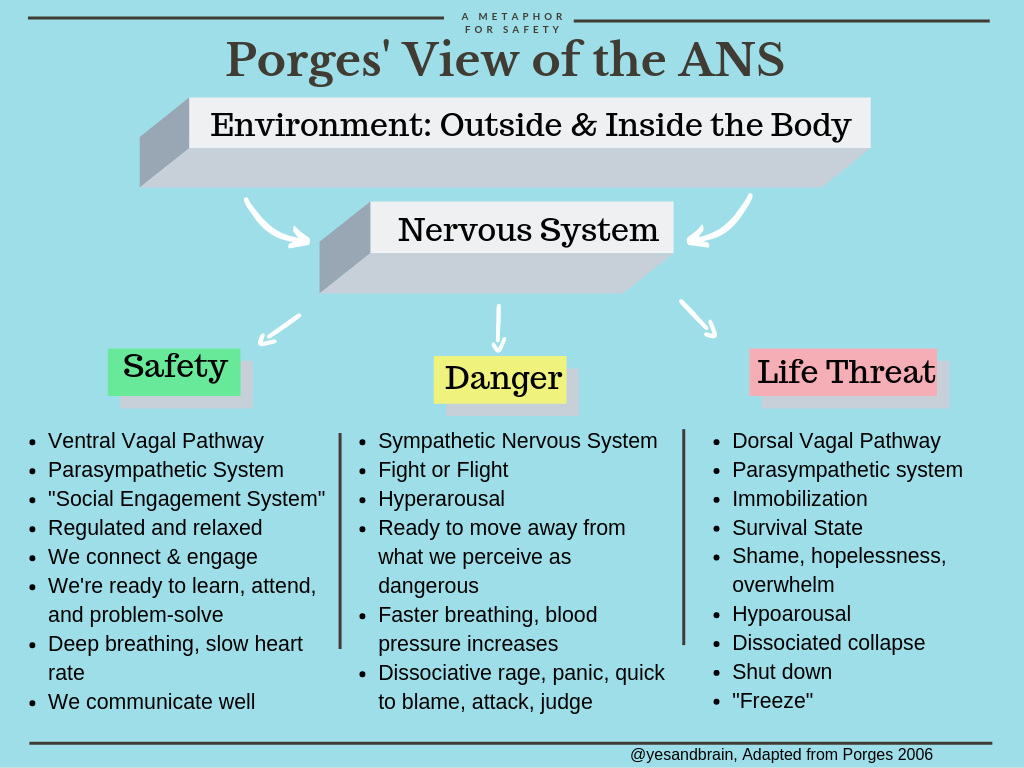

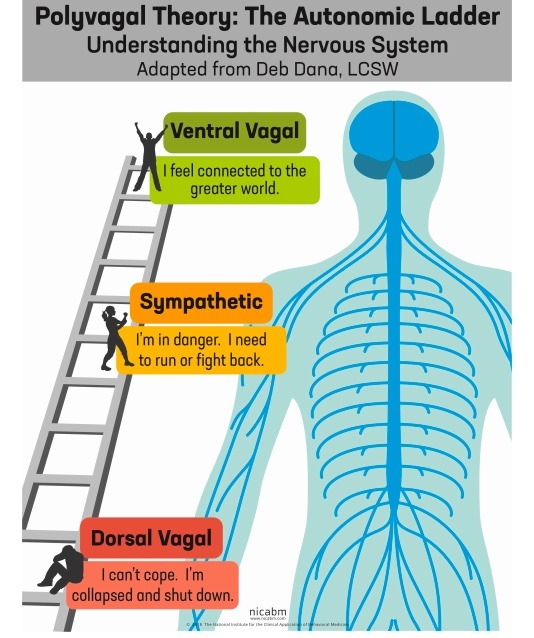

Heavily simplified, Porges’ provides a more complex understanding of the ANS by identifying a three-part hierarchical system that keeps the sympathetic system, and details two distinct pathways of the Vagal nerve (very-important-nerve-super-highway that is the main component of the parasympathetic system):

Heavily simplified, Porges’ provides a more complex understanding of the ANS by identifying a three-part hierarchical system that keeps the sympathetic system, and details two distinct pathways of the Vagal nerve (very-important-nerve-super-highway that is the main component of the parasympathetic system):

The Dorsal Vagus: Brings us out of connection into immobilization.

The Ventral Vagus: Brings us into connection and co-regulation through the Social Engagement System.

He further delineated how these three systems work together, and outlined a coherent system of communication, regulation, and social engagement that operates within the autonomic nervous system. Within this system, he notes that the parasympathetic system is both our system for immobilization AND our system of connection – which extends beyond what we previously understood.

To Help Me Explain This, Imagine a Ladder

VENTRAL VAGAL PATHWAY – (TOP OF THE LADDER)

When we’re at the top of the ladder, we’re in the ventral vagus pathway and have activated our “social engagement system,” which is part of the parasympathetic system. When we’re in this state, we feel safe, we like being connected to others, and we communicate well.

Our heart rate slows down, we breathe deeply, we feel relaxed, we’re drawn to engage, our muscles relax, we use warm facial expressions and vocal shifts to drive our connection, and we can engage in learning, attention, and problem-solving. When we’re in this place, we’re likely to interpret minor stressors from the standpoint of being relaxed and safe, and we’ll recover quickly.

SYMPATHETIC PATHWAY – (MID LADDER)

When we pick up cues through neuroception that we’re not safe, our stress levels rise and we move down the Polyvagal ladder. This is when we slide into the sympathetic nervous system – which you may connect with “fight or flight.” When we’re in this state, we’re ready to mobilize, and our body gives us energy and strength to move away from whatever we’re perceiving as dangerous. However, you can still be in this state without following those impulses and physically moving your body.

When we’re in our sympathetic system, our heart rate and blood pressure increase, we breathe faster, stress hormones flood our body, pain tolerance increases, muscles get tight, we’re often louder and faster, and we can’t process complex emotions. While we’re not great at communicating in this state, we’re able to mobilize to deal with a crisis or possible danger, which certainly has value.

Just like when we’re at the top of the ladder, we filter what we encounter in this state through how we feel at the time. This means we may be quick to attack, blame, or judge – even when there isn’t a huge threat. We aren’t meant to spend a lot of time in this state, though some people’s brains do, especially if they have a history of trauma or adverse experiences.

DORSAL VAGAL PATHWAY (BOTTOM OF THE LADDER)

If we continue to feel stress, our arousal levels increase further, and we slide further down the ladder to the dorsal vagal pathway. As we do that, we land in “immobilization.” This is a survival state that we go to when we can’t escape and we feel helpless and overwhelmed. Even though this pathway sometimes gets called “freeze,” you can experience this state while moving your body.

When we’re in this state, we may have shallow breathing, have less speaking/language skills, a high pain tolerance, avoid eye contact or look down, not be capable of engaging in social exchange, and feel numb or hopeless. When we’re here, we may lose track of time, and our memory is only picking up bits and pieces — which is why trauma memories can be fragmented. The predominate feelings of this state are often shame, helplessness, and overwhelm —which is an inherently lonely experience.

The evolutionary job of this state is to give us a chance to escape if we’re hurt in a bad situation, or to die a relatively painless death if we’re in a situation that is heading in that direction. This state is also not meant to be somewhere we spend a lot of time (though trauma histories and adverse experiences may mean we end up here a lot).

THREE IMPORTANT THINGS TO KNOW:

1. These pathways operate in a phylogenetic hierarchy, which means that they’re rooted in the evolutionary development of our species. In simple terms, this means that if we look to the past, the vertebrae creatures that inhabited the earth way back in ancient times didn’t always have all three of these systems, and our capacity to activate all three of these systems developed from the “bottom up” through the evolutionary timeline. (D) In a parallel manner, these parts of our brain also develop sequentially from the bottom up in utero.

2. We slide between these states in a specified order, which means that if we’re at the bottom of the ladder, we have to slide past the sympathetic system (and engage in a form of mobilization) in order to get out of immobilization (and vice versa).

3. Our life experiences shape the way that we move between these three distinct systems, and adverse experiences (like trauma) can result in our brain defaulting to an over-activation in the mid to bottom section of the ladder. Further, experiences like trauma can mean that we have a hard time navigating through these various states in a healthy way, and this may compromise our ability to recover when we do move into hypo or hyper arousal.

Even without a complex trauma history, it is common for all of us to have experiences that drop us in – and out – of regulation. Keep in mind that our sympathetic system can activate within a range. The person who single handedly lifts a car off of someone after an accident is activating that system – but so are the people who are snapping at their partner in a moment of stress, or people who feel like they endlessly spin in anxiety.

Depending on the experiences we’ve had, it may be hard to distinguish between different types of threat and the actual present risk. For example, someone who was abused as a child likely spent a good amount of time in the sympathetic and dorsal vagal pathways towards the bottom of the ladder. When their brain activated those pathways, that activation became associated with a cascade of physiological shifts, emotions, and experiences. Later in life, if those same systems are activated in a more benign situation, they may struggle to recognize that they’re not experiencing the same level of threat that they previously came to associate with those feelings.

Depending on the experiences we’ve had, it may be hard to distinguish between different types of threat and the actual present risk. For example, someone who was abused as a child likely spent a good amount of time in the sympathetic and dorsal vagal pathways towards the bottom of the ladder. When their brain activated those pathways, that activation became associated with a cascade of physiological shifts, emotions, and experiences. Later in life, if those same systems are activated in a more benign situation, they may struggle to recognize that they’re not experiencing the same level of threat that they previously came to associate with those feelings.

While our brain responding quickly to challenging situations is adaptive in trauma situations, it may mean that someone quickly moves into a place of fight/flight/freeze when the current situation doesn’t actually call for it. This may be reflected in having a “narrow window of tolerance,” which means that their ability to tolerate things without moving into hypo or hyper arousal may be limited. Minor stressors may result in a quick mobilization down the ladder, and the body may not be able to efficiently return to a regulated state once going there.

Once we have developed our natural patterns within this framework, shifting towards healthier patterns can also be challenging. For people who spend a lot of time at the bottom of the ladder, encountering the “mobilization” that comes with sliding towards regulation can feel really scary and cause a retreat back to the bottom of the ladder. Similarly, if someone lives in the fight/flight section of the ladder, feeling calm might actually feel scary, vulnerable, and unfamiliar — causing them to retreat back to the familiarity of mobilization.

So….What Does This Have to Do with Circus?

IN SHORT:

- Circus provides patterned, repetitive, somatosensory, and relational activity that is regulating and healing for our lower brain. In turn, having a regulated lower brain impacts our overall regulation and the way that we organize, understand, and interpret our internal system as we move through the world.

- Circus provides us with a unique opportunity to expand our window of tolerance by providing us with safe and progressive opportunities to practice shifting between states. In circus, we’re faced with the physiological and emotional impact (arousal) of encountering activities that can feel scary or initially out of reach. As we ultimately find mastery of these skills within a safe and supportive context, we experience regulation and a physiological and emotional return to calm. This provides our bodies with an opportunity to “practice” moving between states in a safe way, and ultimately expands our window of tolerance.

- Circus is fun, which makes this process of learning and growth satisfying and reinforcing in a way that isn’t always inherent when we’re doing work to move outside of our “nervous system comfort zone.” This enjoyment allows us to tolerate pushing through the uncomfortable states that we may encounter as we move ourselves beyond our current window of tolerance.

IN-LONG:

It is normal to experience changes in stress and arousal levels in response to the world around us. The goal is to be able to re-regulate and return to the top of the ladder after experiencing that stress, not to avoid it altogether. In order to do that, our system needs resiliency and the ability to modulate between these states.

Because our nervous system is constantly learning from what we encounter, each of us has a body that will respond uniquely to stimuli within this framework — and we need to understand what causes us to move up and down the ladder — and what it feels like for us when we do.

When I say “understand” here, I don’t necessarily mean having a full intellectual understanding that you then use to drive changes in your state, feelings, or behaviors.

There are times — like when we’re at the bottom of the ladder — that we don’t have a lot of access to intellectual reasoning, problem-solving, or self-motivation. Especially for folks who spend a lot of time on the lower half of the ladder, the lower part of the brain needs regulation in order to expand resilience and activate the ability to integrate the gaps that occur between what our body knows (implicit knowledge/memory), how it responds, and the reality of the experience. This type of regulation isn’t something you can talk your body or brain into. To find this regulation, Bruce Perry and Bessel van der Kolk have taught us that the lower parts of the brain need patterned, repetitive, relational, rhythmic, and somatosensory activity in order to heal and build regulation. (H, E)

Many non-Western traditions have understood this for years, and have integrated a wide-range of experiential modalities (movement, dance, rhythm, song, chanting, drumming etc.) to engage and regulate our nervous systems from the “bottom-up.”

REGULATING THE BRAIN FROM THE BOTTOM UP:

Circus provides a perfect opportunity to strengthen our ability to effectively move between affective states, and provides a unique opportunity to regulate the lower parts of the brain. While we generally don’t approach circus with this goal in mind, it inherently offers many tools that help us to regulate our nervous system and effectively learn to toggle from arousal/dysregulation back to a state of calm.

Depending on the circus environment, students and artists may engage in a number of activities that engage our regulatory sensorimotor systems, including: group warm-ups, powerful movement (beats and dynamic moves), touch (partner work), collective shared movement, movement in response to music, rhythmic engagement, slow and intentional movement, muscular stretching and engagement, proprioceptive and vestibular stimulation, breath work, etc.

Because our systems are self-organizing and seek healing, (E) we use this rhythmic, relational, and patterned input to re-organize and soothe the brain. In utero and early life, we experience repeated rhythmic somatosensory activity (gentle movement in utero as our mother moves, maternal heart rate, being rocked etc.) that reinforces a strong implicit sense of safety. When we engage in parallel activity later in life, we’re able to tap into strong implicit (unconscious) memories from our early experiences, which can unlock a new foundation of regulation. (H) If you didn’t have these positive and safe experiences in utero or as a young child, circus may be a way for you to “re-claim” some of these rhythmic movements that your lower brain so desperately needs to regulate. Further, as we engage in these circus activities, the communication systems between our brain and body strengthen, which provide a host of other benefits that we’ll get into in a later blog.

PRACTICE SHIFTING AFFECTIVE STATES:

Whether you’re getting on a trapeze for the first time, or performing a complicated drop — your mind and body had to collaborate to get you there. And you inevitably pushed through some fear, discomfort, and uncertainty along the way.

Through this process, we’re gently inviting ourselves to re-organize our perception of danger, and expanding our window of tolerance. As we find mastery over experiences that would have previously caused us to drop into fight, flight, or freeze modes – our regulatory bandwidth increases, and we learn that the peaks and falls associated with various states of arousal are tolerable and mobile. Through these repetitions, we learn to both passively experience — and actively engage — this modulation between states.

As we harness this ability to intentionally mobilize our state and/or as we experience shifts in state and re-discover that we are still, in fact, safe, we expand our window of tolerance.

Positive Reinforcement

All of this is hopefully happening in a fun and supportive context, which provides further healing and growth in terms of relational connection and regulation. Circus that is taught in a supportive setting is perfect for helping us to acknowledge our current limits, safely push our capacities, and to scaffold an expansion of our personal regulatory system. (Later, we’ll take this further and look at the relational and regulatory impacts of duo/ensemble work and the way that joy and satisfaction impact our brain and body. Another day!)

While this can be overwhelming growth work, the fact that we’re having fun and experiencing lower brain regulation from the somatosensory input reinforces our willingness to engage in this work.

CONCLUSION:

In summary, circus is deeply regulating for the lower brain, and invites us to be in touch with our bodies, to feel deeply, to respond to the sensory information we’re taking in from our body (and the bodies of those around us), to develop interoception (the sense that helps you understand and feel what is going on in your body), and to expand our window of tolerance as we toggle between states. From there, we may potentially be tasked with conveying this complex physio-emotional exchange in a relatable way to an audience — adding an additional dimension to the work.

Safe circus requires that we look inward to our body and listen to what our body is telling us, which is essential for developing a sense of felt safety. As we move into safe connection with our body, our regulatory system begins to organize and integrate. We can access our voice and translate the memories that previously overwhelmed us into language (E), and we learn to connect with ourselves and others in new ways. As we pay attention to what we feel, we invite internal curiosity and foster regulation and connection rather than disconnection — which unlocks new pathways of living.

Throughout this process of connecting our brain and our body, we challenge ourselves and overcome.

We struggle and move through it.

We give our body opportunities to experience regulation associated with repetitive, rhythmic, relational, and somatosensory experiences.

We teach our brain and our body to collaborate and effectively share information.

We become embodied.

And one of the clearest lessons from contemporary neuroscience is that “our sense of ourselves is anchored in a vital connection with our bodies.” (G)

And this is why circus works.

A. The Polyvagal Theory - Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation - Stephen W. Porges, 2011 B. Affect Regulation and the Repair of the Self - Allan N. Schore, 2003 - p. 152 C. Bloch-Atefi A., & Smith, J. - The effectiveness of body-oriented psychotherapy: A review of the literature. 2014 - PACFA, Melbourne. D. The Polyvagal Theory: phylogenetic contributions to social behaviors, Stephen Porges, 2003, Journal: Physiology and Behaviors E. The Body Keeps the Score - Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma - Bessel Van Der Kolk, M.D. - 2014 F. The Body Keeps the Score - Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma - Bessel Van Der Kolk, M.D. - 2014 p. 275 G. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness, Antonio Damasio, New York:Harcourt, 1999 H. The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics: Applying principles of neuroscience to clinical work with traumatized and maltreated children. - Bruce Perry The Body Remembers:The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment - Babette Rothschild Neurobiology Essentials for Clinicians - What Every Therapist Needs to Know - Arlene Montgomery - 2013. The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy - Deb Dana - 2019 Perry & Dobson, 2010: The role of healthy relational interactions in buffering the impact of childhood trauma. Working with Children to Heal Interpersonal Trauma: The Power of Play, Guilford Press Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy (Norton Series on Interpersonal - Pat Ogden, Claire Pain, Kekuni Minton

This article was orginally published at Yes And Brain

All photos courtesy of of Yes and Brain and Lacy Alana. Feature photo image source: Wellcome Library

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!