American Circus Through the Pages of History: A Reading List

I’m always a little jealous of circus scholars that can begin their articles by describing what it felt like to go to the circus as a child. Personally, I didn’t grow up going to the circus. My introduction to the performance of circus arts was the juggling, sword-swallowing, and unicycling street performers at the downtown Toronto Busker’s Festival. I’ve still never seen something that resembles the Modern American Circus, complete with wild animals, clowns, and a big top. What kind of a circus scholar am I?

Considering my research is done with hobbyist jugglers who seemingly have very little relationship with the circus, perhaps I am not a circus scholar at all. Through my interviews with hobbyist jugglers in Canada and the US, I learned that many of them do not identify with the circus or are actively trying to divorce the associations between juggling and circus. Artistic juggler and educator Jay Gilligan echoes this American juggling ethos in conversation with Erik Aberg for their podcast “Object Episodes”:

“When I was growing up in Ohio juggling, we weren’t doing circus, we were juggling. And that was again a really important distinction that we had to tell ourselves… that it wasn’t valid to do circus for some reason… I didn’t even understand that juggling came from circus until I really came to Europe” (Gilligan, “Episode 5”).

According to Gilligan, even within the circus world, some jugglers are positioning themselves outside of juggling because, “for some reason, in the circus, juggling has the lowest status out of all the disciplines” (Gilligan, “Episode 3”).

Despite evidence that hobbyist juggling—and juggling more generally—has less and less contemporary relationship to the circus, I still use the circus as a way to contextualize my dissertation research. My research on contemporary hobbyist juggling practice still engages with some of the big questions scholars are asking about the traditional American circus. And, since I will never get to experience the traditional circus myself, I have turned to books to understand what a day at the circus might have been like.

Even if I wasn’t writing circus history into my dissertation, though, I still think I’d be curious to learn about the modern history of our art form. The history of the American circus is an all-encompassing topic within which to grapple with some of the biggest technological, economic, and political issues that continue to animate societal discourse in the 21st century. For instance, the circus celebrated difference, but also exploited it. It was accessible, but also contributed to exclusionary practices. It was innovative, but also stagnant. It promoted and showcased modernization efforts that made our lives easier, yet also harder, as they contributed to the deterioration of our environment.

All of these complexities make the traditional circus a fascinating and frustrating case study of American cultural origins that refuse easy answers. The rest of this article and my accompanying YouTube video, then, act as my Modern American Circus TBR (to be read) list.

If you have yet to read these texts about the history and theory of the traditional circus, then why not join me in reading them this spring? If you do, let me know in the comments here or on my YouTube channel!

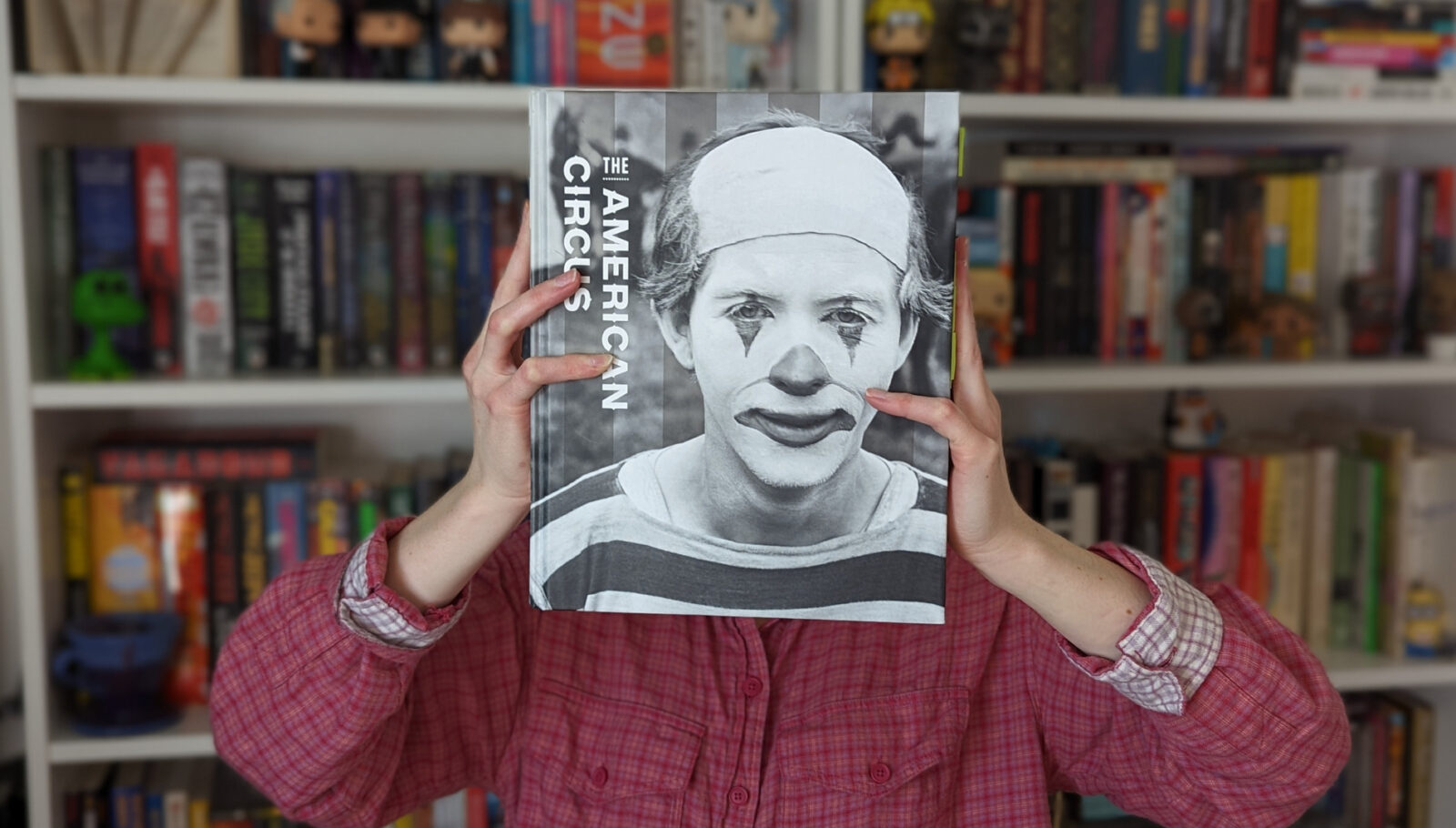

The American Circus

Edited by Susan Weber, Kenneth L. Ames, and Matthew Wittman

Yale University Press, published in 2012

This book contains 17 chapters by different circus scholars on various aspects of the American circus, including chapters specific to the circus parade, the circus poster, circus music, and the circus tent. The first three chapters of this book alone are enough to give you a fairly thorough understanding of how the circus came to America, transformed, and then returned to Britain repackaged.

I have only read five chapters of this book so far, but I am loving it. The writing style varies from chapter to chapter, but overall, I have found each piece quite accessible and entertaining. There are also many full colour images throughout that give much-needed examples of the topics discussed. The images are particularly useful in the chapters on circus posters, circus toys, and the circus in children’s literature, where they are essential to understanding the text. However, they provide a necessary context throughout the book.

The Circus: 1870s-1950s

Edited by Noel Daniel

Taschen, 2008

Speaking of images, this is another wonderful little book on the traditional circus from the 1870s to the 1950s—the height of the American circus. For this book, Daniel gathered 300,000 images of the circus and narrowed those down to the 600 images she curated, most of which were re-printed for the very first time in this publication. The book also features historical consultation from Fred Dahlinger Jr. and essays by Dominique Jando and Linda Granfield to provide some context for the images. The text is included in three languages: English, German, and French.

I haven’t read this book cover to cover, although I suppose you could. More likely you’d want to own it as a coffee table book to flip through and slowly become acquainted with the look of the modern American circus. The images are truly breathtaking and give special insight into a business and performance form that I will never get to witness myself.

Circus, Science and Technology: Dramatising Innovation

Edited by Anna-Sophie Jürgens

Palgrave Macmillan, 2020

This book, across the articles, makes the argument that circus is a useful frame through which to understand our relationship to technology, and it thinks about “technology” and “engineering” quite broadly. Yes, there are chapters specifically on electricity or animation, or how innovation of the circus apparatus affects athletic and aesthetic innovations. But one of my favourite chapters was by Jane Goodall on how P.T. Barnum “engineered” curiosity. One way he did this was by breathing literal life into the museum space and exhibiting performers as curious scientific “natural” discoveries. For instance, a Black man with microcephaly named William Henry Johnson was advertised in both racist and ableist ways, being called “Zip the Pinhead” and “The Missing Link.” Barnum provoked curiosity without putting himself in a vulnerable position by ensuring his claims were “academically sourced” by pseudoscientists of the time. So, spectators could feel superior in their observation of Johnson because it was in the name of a cultural and scientific education.

Artistes of Colour: Ethnic Diversity and Representation in the Victorian Circus

Steve Ward

Modern Vaudeville Press, 2021

The circus is known as a place for outcasts and misfits and people on the fringes of society—and, as evidenced by Goodall’s essay in the previous book, businessmen like Barnum profited off of this inclusion and diversity by reinforcing the otherness of Black and disabled performers. Despite the presence of circus performers of colour in both the American and British circus markets, Steve Ward tells his reader that most of them have been glossed over in the history books because in the end, the circus was still “a political vehicle… that promulgated the idea of a British national supremacy” (26).

I have yet to read Ward’s book, but he says he intends it to be a celebration of the many traditional circus performers from ethnic minority backgrounds, so I’m very excited to pick it up!

Wild and Dangerous Performances: Animals, Emotions, Circus

Peta Tait

Palgrave Macmillan, 2011

This book specifically looks at trained big cat and elephant acts in the twentieth century and how the animals were anthropomorphized to represent human-like emotions for the audience to interpret. Tait writes that most studies of captured wild animals discuss zoos and menageries, despite the fact that a lot of animal rights organizations focus their activism on the circus. She suggests that this is because the role of animals in the circus is less ambiguous than at the zoo, where they can claim to offer sanctuary to endangered species (4). From what I can tell in the introduction, this book doesn’t just criticize the circus for its treatment of animals, as many other narratives of wild animal acts do. Tait also celebrates the performance capacities of these animals and the fact that trainers in the circus recognized the individuality of wild animals before that was a mainstream concept.

__

Regardless of your role within the circus—be it as a performer, a producer, an academic, or an audience member—I encourage you to read about our art form’s history. By picking up one of the books above, you can experience the wonder, magic, and excitement of this iconic American art form, even if you, like me, never had the chance to witness it firsthand. You will also come to appreciate the truly vital role the circus played in shaping American society today.

Works Cited:

Gilligan, Jay and Erik Aberg. “Object Episodes 3.” Object Episodes, 31 Oct 2020, https://www.juggle.org/object-episodes-3/.

Gilligan, Jay and Erik Aberg. “Object Episodes 5.” Object Episodes, 14 Nov 2020, https://www.juggle.org/object-episodes-5/.

Cover image provided by Morgan Anderson.

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!