What Makes Performing Arts Possible? Part Two

In part one to this story, I presented an outline of how performing arts education and production is supported differently in different wealthy countries around the world. A lot of the information in that article demonstrates the unique difficulties of producing non-commercial work, especially with younger art forms like contemporary circus and physical theatre, in America.

Thus, as an American aerial theatre artist, full of questions and hungry for perspective, I ventured on what I call a 6 week Euro-romp. I set up opportunities to shadow prominent directors in theatre and circus, talk to professionals, observe rehearsals and do some of my own creative residency time. I intended to both bring my perspective and experience to my international colleagues processes, and also learn from them ways to cultivate some hope for the future of the field in the States.

Roots

I have always had a stubborn enthusiasm for high quality, imaginative, compelling performing arts, and I’ve always dreamed big. Over the years, my fascination with theatre and contemporary circus has inspired all kinds of unexpected journeys. For example, without any gymnastics or athletic background I decided to become an aerialist when I was 23 years old. With no interest in business, I started a company to enable the production of my own aerial theatre work. When I began the company, I was not prepared for what a challenge it would be to propel an unfamiliar art form forward.

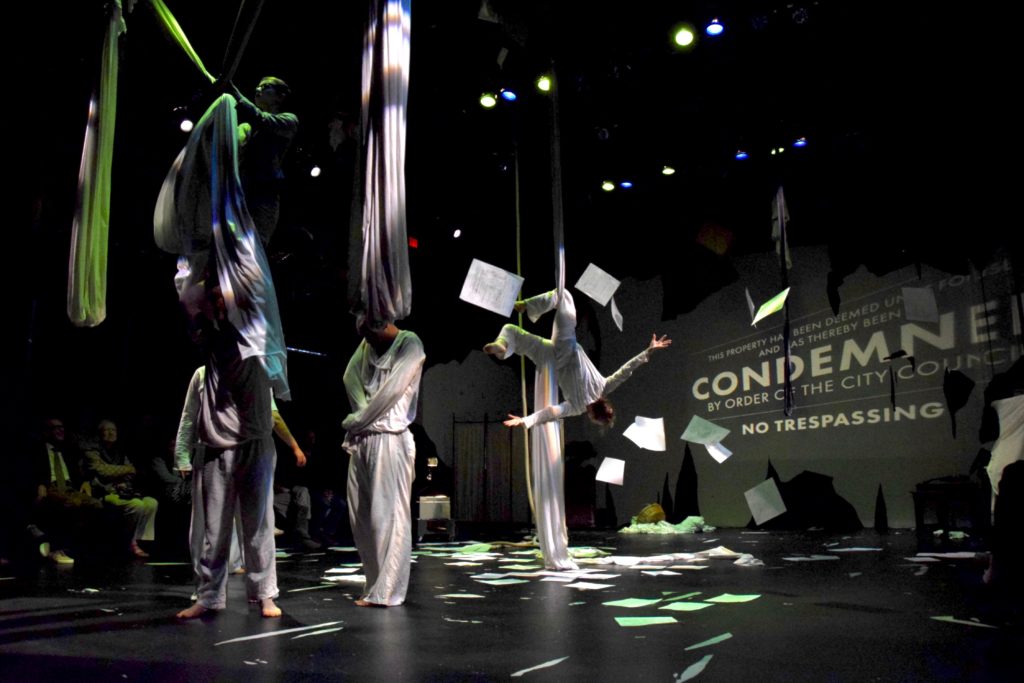

In 2010 in New York City, fellow actress/aerialist Kendall Rileigh and I bonded over our shared enthusiasm for heightened theatrical storytelling– the kind that was so creative and playful that it made us feel like children whose imaginations had been yanked out of our brains and expressed on a stage. We hungered to “create poetic theatrical worlds where aerial acrobatics is a tool for heightened storytelling” and “to tell visually exciting and emotionally compelling stories.” Those words are directly from the mission statement of the company we later founded together in pursuit of such goals, Only Child Aerial Theatre. Only Child has received grants, commissions, and was a selected artist of the prestigious new work development program of New Victory LabWorks; we’ve been featured on NPR, presented in an international festival, and even defined “aerial theatre” for the Theatre Development Fund’s theatre dictionary. Yet, our work has only really been possible because of the thousands of dollars worth of donated equipment, rehearsal space, and professional artists’ time that our community has offered. Building the company and creating the work has come at significant personal expense, and we are still very much in the red despite the ways in which we’ve created visibility and creative opportunity with our work.

Our story is not uncommon in America, but my stubbornness has driven me to seek out how to keep our work not only happening, but prospering. Knowing that the Europeans were doing something that I wasn’t, I ventured to identify what (besides receiving government funding) that might be.

Branching Out

It began with seeing performances from all over the world at the Edinburgh International Fringe Festival, where I saw 19 shows. I also saw 6 shows in London and 2 in Sweden, totaling 27 shows in 6 weeks.

I went expecting that it would be money that made everything there better. In fact, money did not make things better. While it helped make the productions possible, I saw plenty of mediocre high-budget shows and heard stories of dysfunctional creative teams working with big budgets.

I came out of my experience abroad with one lesson:

What makes art good is when the people making it feel safe in their creative process. Yes, money helps make that creative process more elaborate and maybe even more dynamic– but money itself doesn’t make art better.

What’s my evidence?

The first thing to stand out to me was the sense of warmth, welcome and respect I felt in the various rehearsals in which I participated. I have had a very hard time finding “my people” and “my projects” in the States. In the several processes on which I assisted overseas, my perspective and insight was valued because the projects were both relevant to my skill sets, and also because the projects were led by really warm, passionate, communicative people. I was always invited to share observations and suggestions, and they were not only received graciously but sometimes integrated into the work.

I also observed dynamic collaboration among the core teams of each show. I sat in on the final dress rehearsals of Ellie Dubois’ award winning No Show at the Edinburgh Fringe. I watched how Ellie directed her performers, and how they supported each other on and off stage. I saw how this brought an essential level of honesty to the performance, and that honesty is what made it such a special piece of circus.

Mutual respect, freedom, trust and work ethic facilitate creativity and artistic quality.

I sat in a rehearsal at the National Youth Theatre in London where Frantic Assembly’s associate director Simon Pittman worked with teenage actors on a highly physical production of Othello. I observed that though they were teens, these actors were treated as and behaved like professionals in the rehearsal room. The director treated them with complete respect, their work ethic was on point, and they collaborated with openness and patience. The rehearsal was riveting.

I attended the first 10 out of 12 tech rehearsals of a new play called Boudica at Shakespeare’s Globe. Because of recent decisions by the Globe’s board, it is the last show to have amplified sound and high tech effects in that theatre. I watched the creative team and the actors work together to make the most out of that opportunity, to serve a mission they believed in–to make one last vibrant and exciting work on that stage that included modern theatrical tools. It was a stressful day, yet the team maintained an attitude of ease, enthusiasm and patience that facilitated a solid first preview of the show that I also attended just 48 hours later.

In Sweden, I shadowed Cirkus Cirkor director Olle Strandberg in the final week of rehearsal for his new show Under. This was another team that felt like a mix between a family and machine. The focus on the work was razor sharp, but the love, trust and faith in the project among the cast and crew was palpable and intoxicating.

The conclusion? Mutual respect, freedom, trust and work ethic facilitate creativity and artistic quality. In other words: being professional.

Something that permits such a dynamic is making sure there are enough people on deck to fulfill the jobs associated with making and producing a show. Delegation to qualified people who care about their contribution is what makes each mechanism in the production process work. Performing arts can’t happen in a vacuum. Too often, especially in the U.S., ambitious and headstrong artists (hi!) try to do too many jobs at once. It just doesn’t work. You can’t trust someone who is doing work that could be distributed amongst 5 specialized professionals and 2 assistants to do everything well on their own. Immediately such an imbalance throws off a project’s dynamics and inhibits everyone’s freedom. It inhibits trust, confidence and especially creativity. I learned this the hard way.

If I could pick one thing to change in the U.S., it would be to free artists from being solely responsible for their own production management, marketing, and development. It would be somehow incentivizing skilled administrators to partner with artists to give them the headspace to create and collaborate with their creative teams in a safe and generative way.

Thus, the tasks for moving forward to increase our professionalism are threefold (and they’re not easy):

- Get funding for projects and their teams that infuse them with non-disputable value

- Make an administrative base to keep projects organized throughout their development

- Cultivate an environment of trust, generosity and positive energy among colleagues

Planting Seeds

Back in college, I memorized Sonnet 29 by Shakespeare. When I was in London this summer, I found myself reflecting on it. I tried to create with it. I wondered if I could stage it with aerial somehow or make a movement theatre piece inspired by the words. None of my attempts felt right. They were forced and redundant, and none of the improvisations felt fully satisfying. I began to shift my creative focus to be on different material that yielded more fruitful results, but the words of Sonnet 29 kept haunting me: “When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes, / I all alone beweep my outcast state … For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings, / that then I scorn to change my state with kings.” These words echo the lessons I learned during my time abroad.

It is with the deepest gratitude that I reflect on all of the people with whom I shared inspiration, revelations, laughter and challenge on the Euro-romp. It is their love remembered that gives me the vigor to keep going in this neglected field despite the difficulties. It is our mutual commitment to making this field stronger that I hope inspires those who otherwise might get lost in this perceived “disgrace in fortune and men’s eyes” to understand that we can work together to improve our situation. We have to be focused, realistic and cooperative in order to succeed.

Before I left for Europe, I felt out of touch with how to focus my energy on a positive next step in my life and career. While abroad, I experienced the kinds of working conditions, collaborative relationships and social support systems for which I had hungered in New York. The perspective I gained showed me that before changing the external factors in my creative environment: funding structures, administrative infrastructures, education; I need to change my own mindset about my role as an artist in the world. A stifled artist cannot create, and I had allowed myself to question my value to the point of doubt. When I was in places with more defined support systems for circus/physical theatre, my mindset improved dramatically. I began to realize that my work is valued, both by the audiences who’ve enjoyed my work, but also by the international colleagues to whom I offered contributions. Thus, I began to feel more free and inspired to continue. Now that I’m back in the United States, I am approaching my work from the knowledge that it is an important cultural contribution. That it will continue to have value as long as it is truthful, inspired and connected. I can’t change the American performing arts funding system alone, but I can be part of a larger international community of people who value the production of each other’s work. Through connection, communication and diligent work, change is possible. It’s only a matter of time.

Related CircusTalk content: What Makes Performing Arts Possible? Part One

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!