What Does Contemporary Circus Look Like in Palestine?

What is contemporary circus, and what does contemporary circus in Palestine actually look like? When did it start? What do Palestinian circus artists really want? These questions and many more have been under discussion for the past decade in Palestine. To answer them, we must first look back and go through circus’ evolution into the Palestinian circus of today.

The Timeline of Circus

According to A.H. Saxon (2019), in an earlier article about circus history:

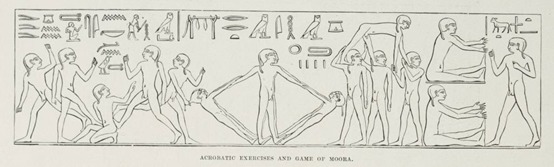

Acrobatics, balancing acts and juggling are probably as old as humankind itself, with records of such acts being performed in Egypt as early as 2500 BCE. The Greeks practiced rope dancing; early African civilizations engaged in siricasi (a combination of folkloric dance and acrobatics), and the ancient Chinese juggled and performed acrobatics acts for members of the imperial court. Clowns have existed in nearly every period and civilization, both as characters in farces and as individual performers.

The origins of the circus as we know it was in England, and it has since seen many evolutions from that modern starting point. Here are the three generations of circus: modern circus, New Circus, and contemporary circus.

Modern circus (also called traditional/classical circus) is the first generation of the circuses we know today, and it came into being in England in 1768. Philip Astley is considered the creator of the modern circus, which is, according to Katharine Kavanagh (2017),“[t]he classical circus as we now know it– in a ring, under canvas, with multiple unconnected acts.” These acts– high-skilled performers, clowns, and animals– are often presented by a ringmaster. Circus in Astley’s time was purely entertainment art, and had several characteristics, such as parades, equestrian acts, acts of skill, circus families, wild animal acts, and clowns.

The second generation in circus evolution is the New Circusor Cirque Nouveau. Kavanagh notes that the New Circus movement began in France, arising from the political unrest of 1968. It broke away from modern circus in different ways: banishing animals from shows, and focusing attention on the human body. Circus shows started to take on narrative or symbolic meanings, conveyed through artistic expression. New Circus also began to connect with other art forms, including contemporary dance, radical theater, and all performing arts in which the body is made central. The most famous example of New Circus is Cirque du Soleil, well-known for shows that tie together separate acts by theme.

Contemporary circus shares with New Circus the centrality of the human body, and animals were banished as well. So, what else defines contemporary circus? And when did it start? Many circus researchers concur that contemporary circus started in 1990s France with the Centre National des Arts du Cirque (CNAC)’s graduation show Le Cri Du Cameleon,which combined elements of theater, dance, and circus. Contemporary circus is connected to contemporary dance and postmodern theater and all kinds of performance arts.

It’s not easy to find an inclusive definition of contemporary circus: it’s a big umbrella term, and the styles of shows under it can vary widely. Some shows are thematic, while others focus on creating moods and feelings. Some shows are based on the ways that characters communicate through gestures, and others emphasize the art of movement. These elements created new categories of art, such as circus theater and circus dance. Mixing these elements created a wide space for different opinions about how to categorize circus shows, and people see and perceive them differently. Some notable contemporary circus companies are Cie XY, CIRCA, and The 7 Fingers (Les 7 Doigts De La Main).

Circus in Palestine

Tracking circus history in Palestine is quite hard. There are no resources or archives available that address circus from between the 16th and the 20th centuries. One of the main reasons for lacking resources in many fields, circus included, is the instability of Palestine’s political situation. Another is the movement of the Palestinian population internally and externally, whether under the Ottoman Empire’s control from the 16th century until 1917, British colonialism (1920 – 1948), or lastly, the Israeli occupation (1948 – today).

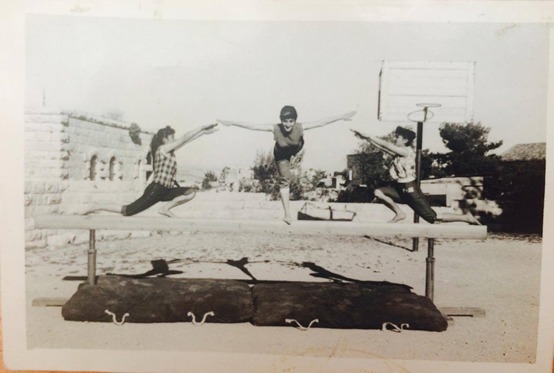

Most of the performances that had been witnessed in the 20th century were athletic events. Gymnastics and acrobatics existed in different Palestinian cities, and sports shows happened on many celebrations and occasions. For instance, this photo (left) was taken in Birzeit, Ramallah, at the site of the future Palestinian Circus School building, during an exhibition organized by the town’s sports college.

All of these factors mean that all records of the circus arts in Palestine were taken in the 21st century, a time when many initiatives were born to establish circus schools, companies, groups, clubs, and training centers. Many of these initiatives took the circus arts as an entertainment art, while others focused on circus education: using social circus methods to deliver circus arts for children and youth, by using the circus skills as tools to achieve social values.

Contemporary circus in Palestine is as new as it is worldwide. Many Palestinian circus artists concur that the starting point of the contemporary circus in Palestine is the 2007 show Circus behind the Wall by the Palestinian Circus School. It was the school’s first show, directed by Shadi Zmorrod. The show combined elements of drama and dance with circus skills such as acrobatics, juggling, trapeze, tissue, and stilts walking. All these elements were applied to support the main aspect of the show, which is its theme. Here is part of the show’s synopsis, taken from the Palestinian Circus School’s website:

Circus behind the Wall is a testimony of what the real-life of Palestinians is: being separated from their families and beloved ones, their land and water by the Wall.

The show came as a response at a time when the Israeli apartheid wall was built around the West Bank in occupied Palestine. Relying on its story as its main aspect, Circus behind the Wall contained all the necessary elements to deliver its message in the most effective way.

The Palestinian Circus School. (2008) “Circus Behind the Wall”

Another example of contemporary circus is the 2018 show SARAB, also by the Palestinian Circus School. Directed by Paul Evans, SARAB is a theatrical circus show that shares the plight of refugees worldwide. The show synopsis reads:

We were forced and had no other options. Pushed on a track with an uncertain end, our destiny is unpredictable. We’re competing to arrive at the unknown. We all have our dreams and wishes and we ambush [sic] to achieve them. Our journey is directed towards an illusion that can’t be described as any more than a mirage. Finally, we arrive. But, have we arrived at our goal? What is our aim? After floating on earth and oceans and narrowly passing obstacles and checkpoints we arrive to what we did not expect, we arrive at the mirage which doesn’t seem to be like the one we’ve pictured in our soul’s imagination. So after all, it really was nothing but a mirage.

The show combined theater, dance, and song with circus skills to create a contemporary circus show that could address political and humanitarian issues. It was the brilliant mix of these elements that gave the show the opportunity to tour around the world.

Contemporary circus in Palestine tends to raise difficult questions and convey serious messages. It is influenced by the history of Palestine as a country under occupation, and by social and political issues in the present. That’s why most circus shows in Palestine have political or social topics. Palestinian circuses tend to use circus skills as tools to communicate and share their ideas with the audience, while other circus creators tend to do circus for the sake of art.

Right now we are living in the time of contemporary circus, and we, the Palestinian circus —artists, companies, schools, and researchers— are all part of developing the definition of the contemporary circus with its new styles, categories, and methods.

References A.H. Saxon, 2019, "circus," Encyclopedia Britannica. Katharine Kavanagh, 2017, "Where are we now?" The Circus Diaries Weidenbach, "Acrobatic Exercises and Game of Morra." Digital Scholarship Archive, Rice University. The Palestinian Circus School

Feature photo: The Palestinian Circus School. Show SARAB

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!