They’re Not Just Women – They’re Superwomen! – The Rise of the Female Circus Performer

Every day across the world, thousands of women perform daring feats of circus agility, whether in the traditional circus under the big top, in a theatre, at a festival, at an open-air event, at a corporate event, or even on the street; circus is an all-embracing art form that can happen anywhere. Throughout antiquity, there have been depictions of women presenting circus-style activities. In ancient Egypt, tomb paintings show female jugglers; Greek vases show female contortionists, and Roman vases show female acrobats. But we rarely stop to think that when the modern circus began some 250 years ago women were seldom seen; it was very much a male-dominated business. But some women did break through the barriers and found circus to be a medium in which they could have autonomy over their own bodies and an agency for their actions. They could find a freedom of expression that challenged the perceptions of femininity as promulgated by men.

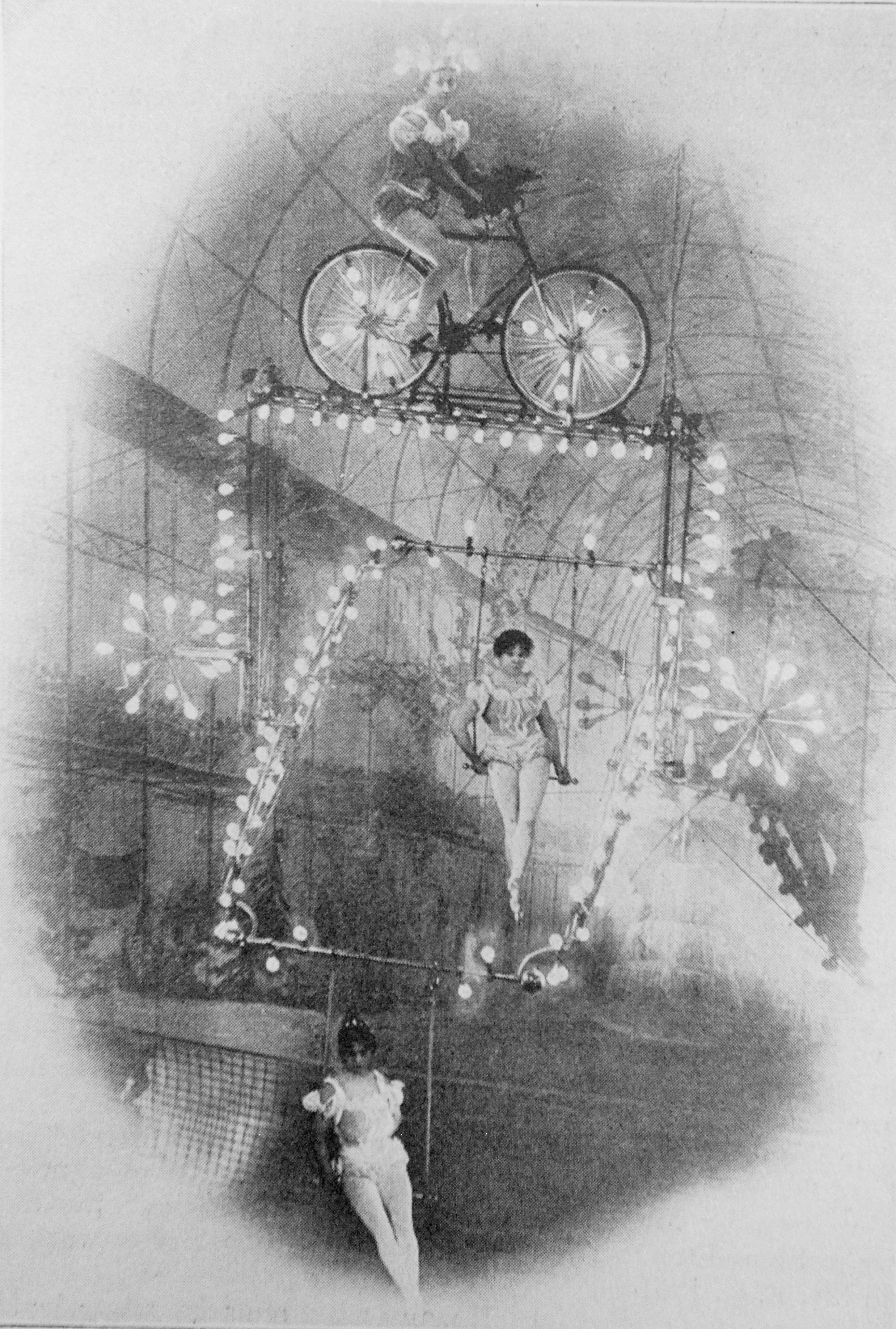

Recently I was searching for a circus image that for an illustration and I was browsing through a collection of art work by the French artist Toulouse – Lautrec. He was a regular visitor to the several circuses in Paris and this was reflected in a collection of sketches he produced between 1888 and 1899. Of the forty-seven sketches that he produced some twenty-five show female performers, many actually during an individual performance. The acts shown are those that one might traditionally expect; equestrian, trapeze, tight-rope, acrobats, animal presentation but, interestingly, a female clown by the name of Cha-U-Kao. Admittedly several of the sketches show the same artiste in various poses but what is important for me is that, at this period in history, women are playing a significant role in the circus. At this point we should remember that the ‘modern’ circus, as we might recognise it today, was a little over one hundred years old. One particular sketch drew my attention. It is entitled Au Cirque; danseuse de corde (The rope dancer)and it captures the moment when a young woman, alone on the tight-rope, takes her first tentative step out onto the wire. Toulouse – Lautrec has expertly caught the drama of the moment. She is seated on a small perch above the wire, her hands beginning to push her body away from the seat. Her left foot is already on the wire and her leg is flexed as she takes the weight of her body; her right leg extending along the wire as she places her foot in preparation for the first step. In the circus sketches by Toulouse – Lautrec he portrays women as performers in their own right. In their own disciplines they are performing equal to, and in some cases better than, their male colleagues and being acknowledged as such. They might dress and wear costumes that define them as women but they are first and foremost performers. As a young friend of mine recently said about her acrobatic performance in the ring, “I am not there to be a costume – I am there as a performer”. In spite of the fact that her costume might emphasise her femininity, for her the performance is paramount.

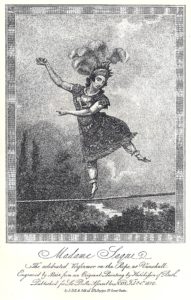

In June 1816 a young French woman by the name of Madame Saqui arrived in London and began to perform daring feats on an inclined tight-wire to a height of sixty feet. She performed both in Vauxhall Gardens and at Astley’s Amphitheatre and became an overnight success. Barely fifty years after Philip Astley had laid down the foundations of the ‘modern’ circus she may not have been the first or only woman to be performing in circus but she did much to raise the profile of the female circus performer and as such became a recognised celebrity. This was at a time when the role of women was very oppressed by the patriarchal society. Madame Saqui and others of her kind was breaking new ground and helping champion the cause of women.

It seems that anything a man could do in the circus was very often bettered by women. In 1838, the self-proclaimed American ‘Lion King’, Isaac Van Amburgh made his debut in London. Much loved by the young Queen Victoria, his act became a sensation but it also paved the way for the appearance of several ‘Lion Queens’. The earliest mention of a female working with wild cats appears in the Liverpool Mercury on 1 August 1845;

A Mrs. King, who takes the title of the Lion Queen, has been exhibiting her foolhardiness at Glasgow, by going into the den of the lions and tigers at Wombwell’s menagerie.

Although Mrs. King may have been the first recorded Lion Queen, perhaps the most famous for her exploits was Ellen Chapman, often referred to as Nellie. Ellen was born in 1831 so was only a teenager when she began performing with Wombwell’s menagerie. Exactly when she began performing is not clear but it is likely to have been sometime in 1846. One of the earliest records of Ellen being mentioned by name appears in the Liverpool Mercury of 22 January 1847;

JUST ARRIVED AND NOW EXHIBITING IN THE HAYMARKET … WOMBWELL’S ROYAL MENAGERIE … The Establishment is accompanied by Miss Chapman, “The Lion Queen”, who will perform daily with her Royal group of nine Lions.

So daring was she in her performances that she was said to have ‘out Amburghed Van Amburgh himself’. Other Lion Queens were in evidence at this time. A former lion tamer claimed, in a lengthy article on the subject in the Morpeth Herald of 13 January 1872 that Polly Hilton [Hylton], the daughter of the menagerie owner, was one of the first Lion Queens and appeared at Stepney Fair. Hylton’s was a rival company to Wombwell’s but a much smaller outfit in general.

When Jules Leotard became the first performer of the flying trapeze in 1859, it was not long before women matched him in his exploits. One of the first female flyers was a Mademoiselle Azella, who performed with Hengler’s Circus and at other venues in London during the late 1860s. Although she won many plaudits for her performances there were always those men who were critical. In September 1867, The Hereford Times reported on her performance at the Hippodrome in London;

What is the gentle sex coming to, with its pantalettes and its muscular and manly development?

And again, in April 1868, The Oxford Times was of the opinion that;

The direction of female thought now-a-days seems to be to unwomanise women … It is time that the Legislature, which can preclude Oliver Twist from the theatres, should also stop these more degrading exhibitions.

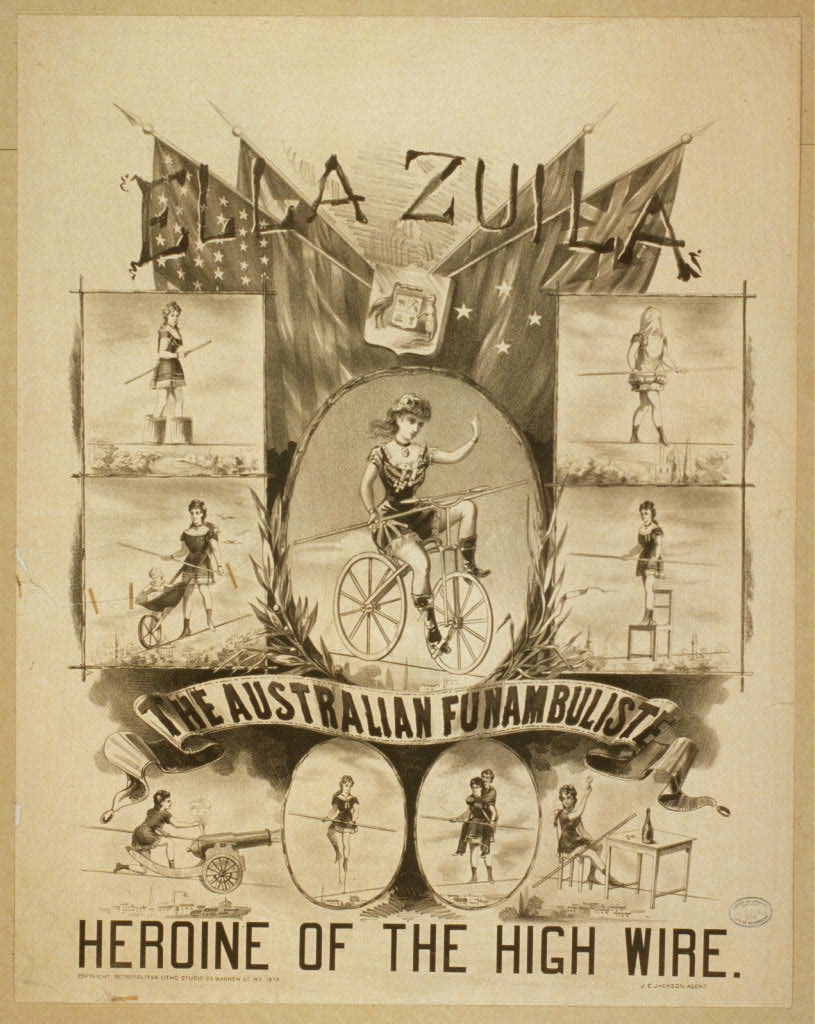

For all the criticism, it did not stop women from competing with men. When Charles Blondin, the high-wire walker, crossed Niagara Falls in 1859 his daring feat only served to produce a whole host of ‘Female Blondins’. Female flyers and high-wire walkers had made their mark and were here to stay but the diminutive fifteen-year-old Rosa Richter, who performed under the name Zazel, became the first-ever human cannonball when she appeared at the London Aquarium in 1877. She became a victim of the Acrobats’ and Gymnasts’ Bill of 1880 and was forced to move to America, where she was engaged by Barnum & Bailey’s Circus.

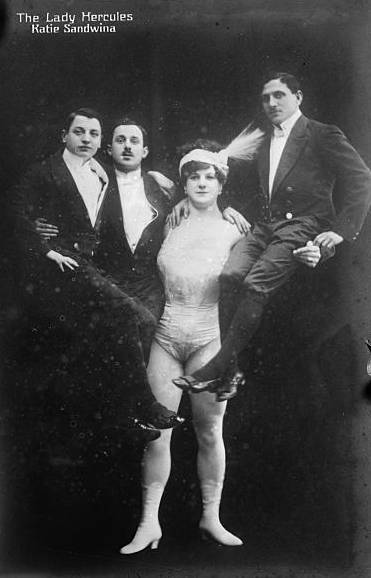

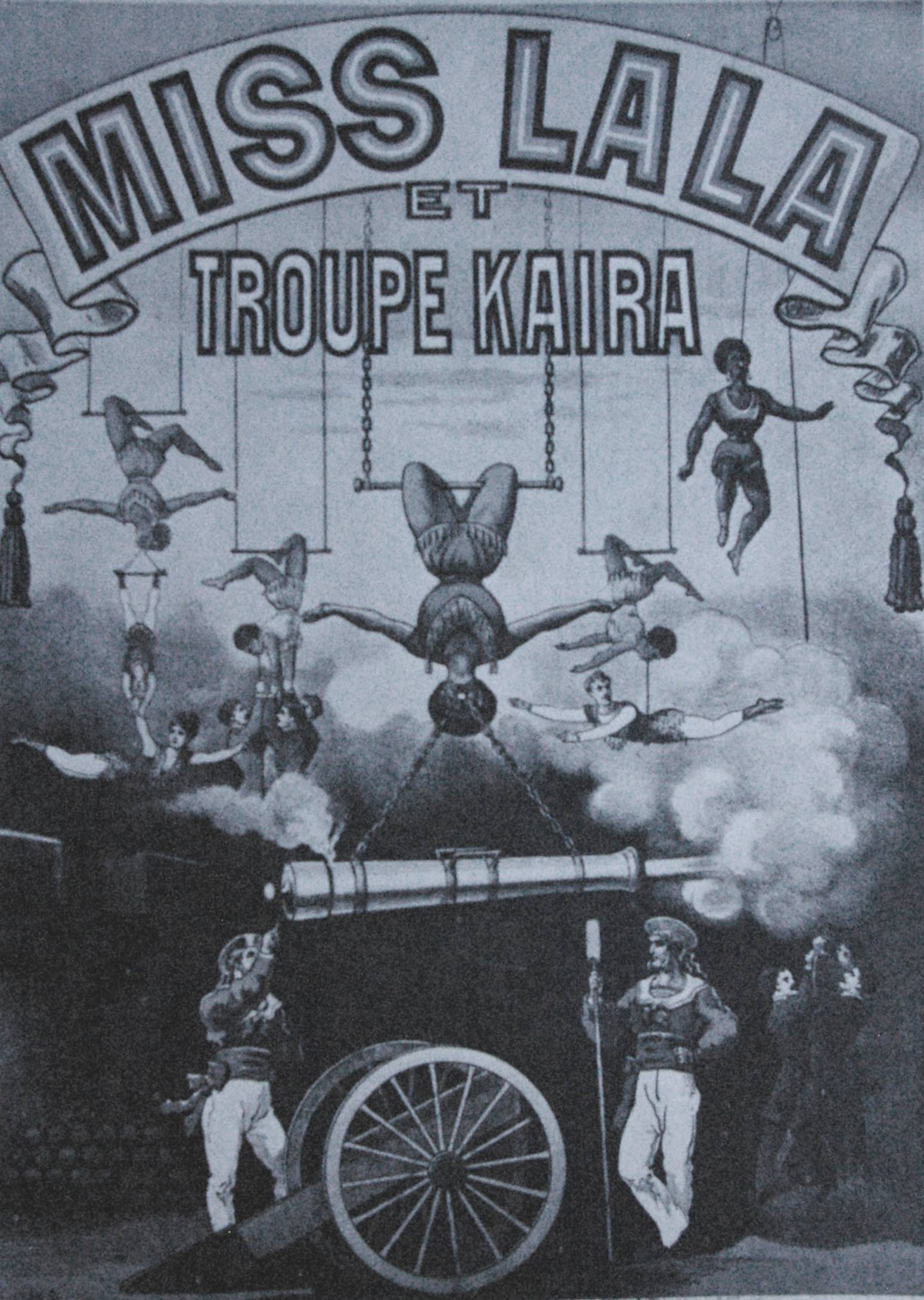

Male feats of strength were common in the Victorian circus. Miss La La (born Olga Brown) and Leona Dare were both well-known for their ‘iron-jaw’ acts but when the strong-woman Katie Brumbach adopted the stage name of Sandwina she struck a blow for women. Anecdotal evidence reports that she took this name after beating the well-known strong-man Eugene Sandow in a weight lifting competition. Sandwina was at the forefront of the fight for female emancipation and was a vice-president of the Suffragette Ladies of the Barnum & Bailey’s Circus. Welsh born Kate Williams, performing as Vulcana, was another proponent of female emancipation. She travelled widely and in Australia she was avidly listened to. She changed women’s thoughts about health and beauty, as here reported in the Melbourne edition of Punch 2 January 1904;

Physical culture … was to men an inspiration much followed. But, with the advent of Vulcana, many women who previously had a horror of athleticism, believing that it destroyed their femininity, have been quite won over.

As the circus developed and spread throughout the world so many more women became involved, and I have only briefly mentioned some of the significant early figures. Although many of them may not have been particularly politically minded, by their very actions they became the vanguard for women’s rights and the demand for emancipation. The circus allowed women to compete on equal terms with men and, in some cases, to outdo them. Some became household names; some were celebrities in their own right; some were divas, and some were simply outrageous but they were all strong women who challenged and sought to change male perceptions of womanhood. A little while ago I was discussing circus with the eminent Hungarian clinical psychologist, Dr. Elvira Lux. She had always been a life-long fan of the circus and as a young girl always dreamed of being the beautiful lady on horseback. When I touched upon the roles of women in the circus and how circus had empowered them, she said to me; ‘But women have always been strong, it’s just that men don’t realise it’.

Today there are many female circus performers, too many to individually name, who follow in the footsteps of those earlier pioneering performers. My recent book Sawdust Sisterhood; How Circus Empowered Womenis an acknowledgement and a celebration of how, across two centuries, the circus has empowered women and allowed them to compete and succeed in a predominantly masculine world.

Doctor Steve Ward’s book Sawdust Sisterhood; How Circus Empowered Women can be bought in most good bookshops; from the Amazon websites; or directly from the publisher, Fonthill Media, on Sawdust Sisterhood: How Circus Empowered Women – Fonthill Media

Doctor Steve Ward’s book Sawdust Sisterhood; How Circus Empowered Women can be bought in most good bookshops; from the Amazon websites; or directly from the publisher, Fonthill Media, on Sawdust Sisterhood: How Circus Empowered Women – Fonthill Media

His other works are;

Beneath the Big Top; A Social History of the Circus in Britain

Father of the Modern Circus; Billy Buttons; the Life and Times of Philip Astley

Circus Notes and Jottings

Artistes of Colour; Ethnic Diversity and Representation in the Victorian Circus

Nineteenth Century Circus Poster Art

The Victorian Circuses of Leeds; A Guided Walk

Steve is also available as a speaker on this and other circus topics. Inquire: [email protected]

.

.

The title of this piece is taken from a comment made by a young boy on watching an aerial routine high in the atrium of a shopping centre. Main Image: Olga Frei-Denver Stop frame photograph c. 1950 - Author's collection / All images are courtesy of the author.

.

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!