The Rise of the New Woman Within the Circus

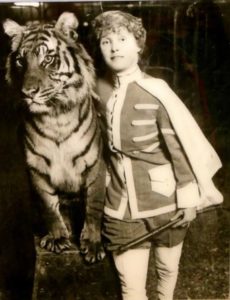

Women have always had a place in the circus, but it would not be until 1896 that the “New Woman” would join the ranks of her male contemporaries under the big top. These “New Woman” acts were often segregated sororities, featuring women performing ‘death defying’ stunts in form fitting costumes in an arena that “no man was allowed to occupy” (Davis 2016: 175). Trapeze artist and strong woman Charmion (b. Laverie Vallée) would shock the world on Christmas Day 1897 with her infamous trapeze disrobing act at Koster and Bial’s NYC vaudeville theatre, an unapologetically provocative display of female sexuality and muscularity that would prove equal parts divisive and intriguing to American audiences (Gils 2013: 1). Katie Sandwina, a German weightlifter featured by Barnum & Bailey, would go on to be described as a “Giantess in Strength.” Big cat trainer Mabel Stark boasted of her ‘network of scars’ that mapped out her body from the bites she endured from her beasts (Davis 2016: 175).

The New Woman ushered in a new wave of racism and sexual fetishism within the circus, with white women continuously being marketed as virginal, pure, and civilised, in stark contrast to the sexually charged nudity associated with ‘exhibitions’ of women of colour (2016: 177). There was a cultural insistence forced upon female aerialists in particular to be portrayed as virgin vestals, as fear of maternity might provoke anxiety in the audience (Stoddart 2000: 170). The moniker prescribed was ultimately superfluous, as the mere presence and publicity surrounding the New Woman served as a new excuse to peddle and promulgate sex in the Victorian era (Davis 2016: 175).

The increase of woman’s presence within the profession did not proceed without vehement criticism. Media scholar Robert Allen claimed that theatre and circus “sharply confounded the rationalistic idea that the world was what it seemed” with its emphasis on “mimicry, spectacle, and inversions of class and gender” (2016: 175). Critics claimed that circus performers (and the audiences the circus attracted) did not engage in “productive labour”, claiming that the circus promoted “idleness, intemperate drinking, profanity, a taste for low company [and] boisterous vulgarity” (2016: 176). In Antebellum America, circus women were considered disrespectable, with purity reformers and critics citing their costuming as the main offender. Davis cites one woman recalling her grandmother’s explicit forbiddance upon her seeing the circus, stating that “God never intended that women should go only half dressed and stand up and ride on horse’s bare back, or jump through hoops, in the air” (2016: 175).

Purity reformers frequently equated the New Woman to prostitutes, as both “exposed their bodies for pay” (2016: 176). This sexual constraint of circus women eventually led to showmen publicising their female performers as decent and godly. Posters began to feature (white) women and their families, painting a godlier image of women who otherwise defied social norms. In Antebellum America the bourgeois was highly segregated, with men engaged in the workforce while women were constrained to the home; as a result, circus audiences were primarily men, which led to an increased censure of female bodies under the big top (2016: 178). The mid- nineteenth century served as a catalyst for the ultimate blurring of gendered lines within the (upper-class, white) social spheres of the United States, with women joining the workforce outside of the home in increasing numbers and men and women beginning to frequent shared after-work spaces. This intermingling of the sexes brought about a sense of anxiety in many traditionalists. Hull House founder Jane Addams said, “Never before in civilisation have such numbers of young girls suddenly been released from the protection of the home and permitted to walk unattended upon city streets and to work under alien roofs” (2016: 178).

This mixture of the sexes in the “civilian” world would bleed into audience integration within the circus, but it did not decrease the criticism and often scientifically inaccurate views of the female bodies both in and outside of the big top. Critics of the increase of female athleticism in both the circus world and private lives expressed concerns over everything from the use of the bicycle (fearing the saddles would serve as masturbatory tool), criticism of “circus face” (bulging eyes, clenched jaw), and accusations of “race suicide” as the New Woman delayed or deferred motherhood altogether in pursuit of education, labour, and activism (2016: 181). While many critics argued against the “near nude” costumes of circus women, others argued for the unlacing of corsets of performers and civilians alike, not out of concern of safety but out of fear that corsetry would restrict the blood flow of the New Woman athlete to her nether regions, creating a hyper- sexualised woman that was at odds with purity culture of the time (2016: 182).

Circus proprietors had already begun to market their circus women as pure and godly in an effort to combat the puritanical views of the audiences they were trying to attract. These advertisements pushed women of “good breeding”, often European (even when this was empirically untrue), with a balance of home and work life (always with a stronger commitment to the world of domesticity) (2016: 183). Circus women were expected to “style and smile” in their acts, an approach that was intended to invite the audience to take equal pleasure in watching the women perform that still influences contemporary circus (Tait 2008: 182). Bertram Wagstaff Mills of Bertram Mills Circus responded to one audience member’s shock at the abilities portrayed by circus women by stating that he could “mount the most extraordinary circus using only innovative female performers.” These defences of female performers were not without the continued reassurance of the femininity and domesticity that had come to be expected to accompany all circus women. Trapeze artist Lillian Leitzel lamented over the difficulties shouldered by circus women, stating that women were expected to “have the double burden of reproductive and physical labour”, simultaneously appearing physically fit, looking their best, and existing without domestic privacy, conditions Leitzel claims would “drive the average woman frantic” (Tait 2005: 94).

Class was a huge proponent surrounding circus women, with an increasing need to present female performers as women from high class and respectable families emerging in the twentieth century. Circus stars Josie DeMott Robinson, Lillian Leitzel, and May Wirth all hailed from old circus families and were publicised as being appropriately feminine, domestic, and daring (Davis 2016: 184). Upward mobility was reserved for men and men alone; a woman who came from nothing and dared to bare her body and taunt death was far too scandalous for most audiences. Any unwed female performer would be said to be on “the threshold of marriage”, hailed as chaste until otherwise taken by a husband (2016: 184). Even female circus animals were expected to assimilate to certain preordained views of femininity; Johanna, a chimpanzee on tour with Barnum & Bailey, was marketed as pure and chaste, a stark contrast to the descriptors reserved for her chimpanzee “husband” Chiko, who was said to be sexually aggressive. When Chiko died in 1894, circus writers claimed that Johanna “bemoaned her fate”, alleging that the female chimpanzee “covered her eyes with perfectly shaped hands for nearly a month” post her “husband’s” death (2016: 185).

Women continued to be sexualised and viewed as lesser throughout the twentieth century. In the nineteenth century, when circus women were still considered novel, being cited as the “first woman X” worked in the favour of proprietors and performers alike when it came to generating interest and audience attendance, but by the twentieth century the allocation of the moniker “woman” served to alienate and classify circus women as secondary and of lower status than their male counterparts. When trapeze artist Lena Jordan achieved the first triple somersault in flying trapeze it was archived as the “first woman” rather than “first performer” by Guinness Book of World Records; as a result, the “first” triple is often allotted to male trapeze artist Ernie Clarke, despite Jordan’s claim of having achieved it before her male colleague (2005: 94). The history and accuracy of the “first triple” is still thrown into question today; circus history, much like history as a whole, is fragmented and biased within the best of retellings, with the documentation of circus bodies, particularly muscularly excelling female ones, existing solely within the realm of convenience (Tait 2006: 10).

The twenty-first century has seen an increase in equality and respect for circus women. “We’ve come a long way in the profession since I began,” says Richie Gaona. “Some of my most dedicated and advanced students are women” (Gaona 2018).

Bibliography Davis, Janet M. “Respectable Female Nudity.” The Routledge Circus Studies Reader, Routledge, 2016, pp. 173–197. Figure 1: Charmion’s Trapeze Disrobing Act Figure 2: Katie Sandwina Figure 3: Lillian Leitzel Figure 4: Mabel Stark (https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/48808/mabel-stark-lady-tigers) Gaona, Richie. Personal Interview. May 2018. Gils, Bieke. Women Who Fly: Aerialists in Modernity (1800-1930). The University of British Colombia (Vancouver), 2013. Stoddart, Helen. Rings of Desire: Circus History and Representation. Manchester: Manchester U Press, 2000. Print. Tait, Peta. Circus Bodies: Cultural Identity in Aerial Performance. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005. Print. Tait, Peta. “Female Pleasure and Muscular Arms in Touring Trapeze Acts.” In Victorian Traffic, edited by Sue Thomas, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2008: 178-189. Tait, Peta. “Re/membering Muscular Circus Bodies: Triple Somersaults, the Flying Jordans and Clarke Brothers.” Nineteenth Century Theatre & Film, Vol 33, No. 1. Summer 2006: 26-38. .

All photos provided courtesy of Morgan Barbour. Feature photo screenshot of Charmion’s Trapeze Disrobing Act

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!