Somersaulting Out of the Archive: Facets of Circus Studies in German-Speaking Countries

A conversation by Mirjam Hildbrand & Anna-Sophie Jürgens

In times of climate catastrophe, refugee crises and Covid-19, the question of the responsibility that artists and scholars have is becoming increasingly urgent. What is the role of circus within society? How far does this form of art and entertainment correlate with historical and contemporary social interests? How does circus research position itself as a relevant field of research within academia in the 21st century? Those questions will be explored within the series Adventures in Circus Research–Facing a New Decade, curated by academic Dr. Franziska Trapp. By featuring circus researchers, we give them the space to explain the nature and significance of their research directly to the circus community and to highlight the practical impact of their research on the circus world and its relevance for society.

Within this first conversation Mirjam Hildbrand, Ph.D. candidate at the Institute of Theatre Studies at the University of Bern, and Dr. Anna-Sophie Jürgens, Assistant Professor at the Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science, explain how the circus of the late 19th and early 20th century is forming our present-day art form. Contemporary cultural policies and funding systems are thereby taken into account just as much as contemporary incarnations of (horror) clowns and the experience of our technological future.

The number of scholars exploring circus in German-speaking countries is still quite small. Belonging to this circus research community – within Theater and Performance Studies, Literary or Cultural Studies – you easily attract attention, as if you were wearing a clown’s costume. This is how we, Anna-Sophie Jürgens and Mirjam Hildbrand, were introduced to each other by a librarian at the Theater Collection of the Freie Universität Berlin: as two academic clowns studying historical circus documents. Of course, we immediately wanted to know what kind of clown the other is and why she pursues academic research adventures on circus.

Anna-Sophie Jürgens: Mirjam, you are a circus programmer and a theater scholar. How did you come to be interested in circus?

Mirjam Hildbrand: My research interest for circus has its roots in the time when I was studying dramaturgy in Leipzig, Germany. During my first semester, I had to prepare a short presentation for a stage design class, and I decided to present a set design of a contemporary circus show I had seen shortly before. But, whilst preparing, I felt uneasy: How would the professor as well as my fellow students react? Even though my study program was not focused on dramatic theater it seemed inappropriate to talk about a circus show in the classroom – but I did it anyway. This is how it all began. A couple of years later, I started to work for the project Station Circus, a venue for contemporary circus in Basel, Switzerland. Being responsible for fundraising, I repeatedly noted that sponsors would not support the project because we curate circus shows. Since circus is not considered an art in the German-speaking countries, I was – of course – not really surprised by these reactions. But I began to wonder more and more why we are, at least in the German-speaking context, so sure that circus is not art? And why are circus and theater, both performing arts, actually valued so differently? Why did I feel uneasy to talk about circus during my theater studies class? Why is there so little academic interest in circus? Well, what is actually the problem with circus?

ASJ: And it is because of all these questions that you are now studying historical circus documents?!

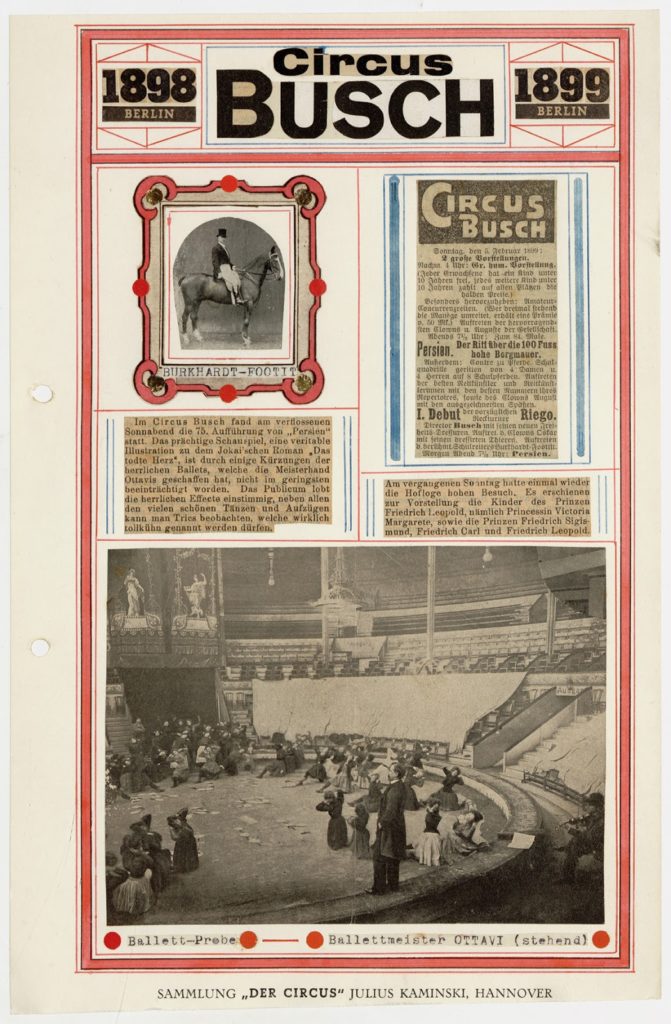

MH: Exactly. When I started looking for answers five years ago I could not find a satisfactory explanation for what happened in the past that would explain why we have this “problem” with circus today. Since I really wanted to understand this narrative of circus as a “non-art”–by the way, you could also replace the term with synonyms like “pure entertainment“, “commercial art” or “low art“ – I began to spend time in various archives in Berlin collecting historical documents about circus in the 19th century.

ASJ: What did you discover? Are you able to answer the questions you started with?

MH: I discovered some sources saying that in 1888 the German theater directors’ association had asked German authorities to legally prohibit circus performances or at least to restrict them to “trick riding and gymnastics.” This and other examples show that in the late 19th century the (not yet subsidized) bourgeois, drama-based theaters suffered from the fierce competition with the highly successful circus performances – not only on an economic but also on an aesthetic level, as circus companies at that time also staged narrative plays. This competition not only led to political lobbying against circus by theater associations but theater professionals also discredited circus arts-based on questions of taste, education and moral values. However, the circus companies remained successful until the 1910s. After the war, a lot of circus companies disappeared and circus buildings were torn down, while at the same time dramatic theater was established as an institution of “high” culture. In my opinion, precise knowledge about the historical development of the image of circus is very important for current debates on cultural policies concerning circus – also because our funding system is based on assumptions and values of the 19th century. To get back to your question: I still have questions and I luckily have two years of Ph.D. circus research adventures ahead. But, what about you: You did your Ph.D. on circus in Literature. What made you interested in researching circus?

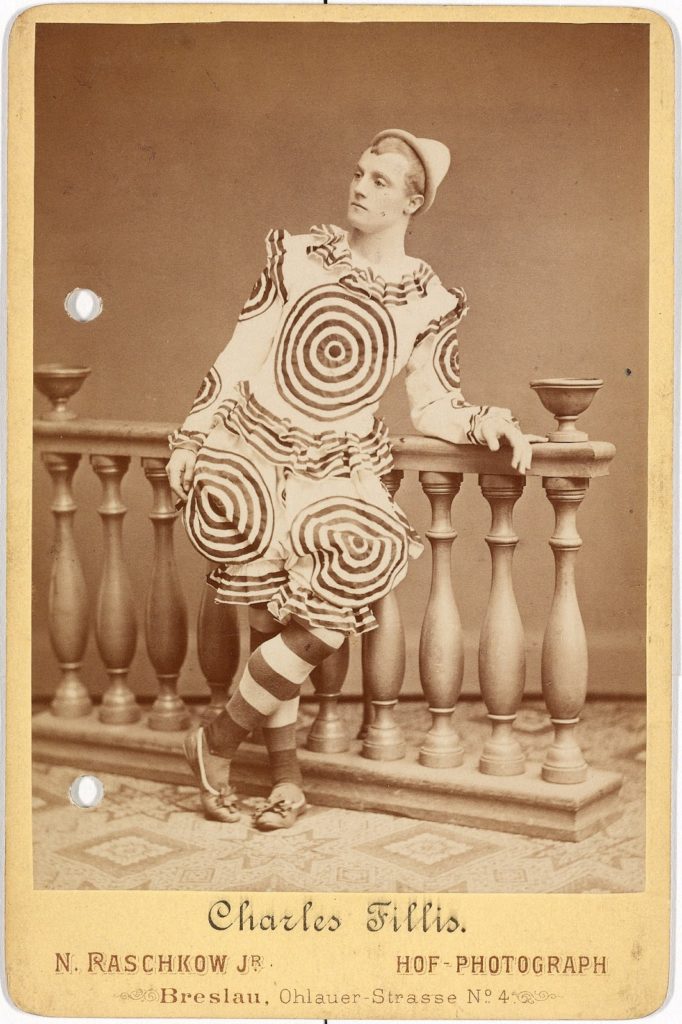

ASJ: I am trained in Comparative Literature, but driven by my interdisciplinary research interests I have expanded into Popular Cultural/Entertainment Studies. I seek to gain a better understanding of how popular entertainments – circus in particular – of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were, and are, formative for our present. In particular, I am interested in the multi-dimensionality of the circus’s cultural and aesthetic capital in fiction and other media such as film and comics (embodied, for instance, in violent and cannibal clowns, epileptic dancers and freak performers). I am equally fascinated by the richness of pathological body aesthetics oscillating between clown humour and violence (as typified by Frankenstein-clowns and mad scientists). These phenomena are powerful manifestations of what we have found funny and scary over time; and of what we define as beautiful and ugly, normal and abnormal… and indeed “human”.

MH: The librarian who introduced us told me that you were studying historical documents on clowns. Why are you particularly interested in clowns?

ASJ: I explore historical and contemporary cultural manifestations and imaginaries of the clown character and its fascinating performance histories. I am interested in how the clown’s contemporary incarnations –for example, Stephen King’s It or Todd Phillips’ Joker – evoke and lead back to late-19th century (re)presentations of violent clowning. In comparison to other phenomena of the popular stage, eccentric, out-of-proportion violent physical comedy and its influence on, for example, fin de siècle and avant-garde (play) writers and artists, are a surprisingly underexplored field of research and discussion. The clown, one of the most durable personifications of human experience, participates in a dense web of cross-fertilization between fiction and reality in contemporary culture and interacts with technology, thus creating significant cultural discourses throughout time.

MH: Contributing to debates on technologies seems very relevant for the societies we live in. How exactly do you link the circus clown with technology in your research?

ASJ: Emerging from my past research and circus-related interests, my current project draws on stories, pictures, historical records, aesthetic and performance styles and theories created by humankind at the crossroads of engineering and comedy for over 100 years. In cultural discourse, our technological future is populated by wild-running killer machines, including Terminators and infamous tripods. Harbingers of a looming techno-apocalypse, they epitomize the extent to which we grapple with the definition of the human experience of technology and with our response to technological advancement. Studying comic performance and technology in circus contexts and beyond will not only enable improved understanding of how we embrace, tame and engage with technology-related fears, uncertainties and desires, but it will also uncover comic visions of a technological humanity; and maybe help rewrite the stories we tell about them. A forthcoming edited collection on Circus, Science and Technology, which I put together based on a 2018 conference on “Imagineers in Circus and Science” (ANU, Canberra), examines some of these phenomena. The book investigates to what extent the engineering of circus and performing bodies can be understood as a strategy to promote awe, how technological inventions have shaped circus and the cultures it helps constitute – and how much of a mutual shaping this is. I think these themes resonate quite well with your research!

MH: Indeed. In my research on the historical circus practice in Berlin, I am also engaging with technology and engineering: Around 1900, the circus companies procured the latest technologies such as electric lighting, projection effects, hydraulic systems and revolving stages for their buildings. Studying the historical documents on circus, I realized that the circus shows at that time consisted of not only programs with various acts, but also of full-length narrative shows dealing with current societal topics and themes from tales, operas, sagas, etc. using the latest technologies. These multimedia circus shows in the circus buildings reminded me of the theater concepts in the 1910s/20s of avant-garde artists as Erwin Piscator, Max Reinhardt and László Moholy-Nagy that are often discussed within Germanophone theater historiography. Although circus served as inspiration for those famous artists, circus practice itself has attracted relatively little research interest so far.

In summary, in our first conversation we discovered that as colorful academic clowns and circus scholars, we both not only study historical circus sources and the links between technology and circus arts but are also fascinated by the historical avant-gardes and their relationship to the circus. This is why together we organized the first symposium on “Circus and the Avant-Gardes” in Berlin in March 2020, which will be followed by a second symposium at the Institute of Theatre Studies at the University of Bern that will take place online on 13-14 May 2020. The symposium will be held in German– if you are interested in participating, please contact us via email. Don’t miss our article “Circus Arts and the Avant-Gardes”, published with the online journal w/k, and follow our circus and avant-garde adventures on Twitter: #circus_avantgardes!

Feature photo courtesy of För Künkel & Mirjam Hildbrand

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!