Rosgoscirk: 95 Years of Russian Circus

For almost a century, one centralized organization has been preserving and promoting the grand Russian circus tradition at home and abroad.

Throughout the political and cultural turmoil of the twentieth century, one Russian circus entity has stood remarkably strong, but the Russian State Circus Company’s origins go back even further that that. In imperial Russia, circus was so beloved that Catherine the Great, Nicholas I, and Nicholas II all commissioned circus buildings. After the Russian Revolution, Vladimir Lenin recognized the popular appeal (and the profit-making potential) of circus and mandated state appropriation of private circuses. By the mid 1920s, a new national association of circus companies had incorporated all private circuses into local units of a federal program.

The government also invested in developing circus as a national art form, creating the world’s first professional circus school in 1927, the State College of Circus and Variety Arts. Critics clung to the old ways of apprenticeship within circus families, but the new school was incredibly successful, graduating phenomenal performers and inspiring the formation of professional circus training institutions around the world. Even though many foreign performers had fled Russia after the revolution, the government’s efforts not only kept circus alive but also made it thrive; during the communist era, 50 to 100 circuses operated throughout the Soviet Union, performing to wide acclaim for tens of millions of fans.

Throughout the twentieth century, many Russians agree that circus was more important and popular than theater, dance, or opera. And although Russia prided itself on its cultural legacy of circus, the art form was also popular in many of the other countries that formed the USSR. In 1957, the circus government agency incorporated circuses from throughout the Soviet republics into one association, Soyuzgostsirk. Like the Russian czars before them, Soviet leaders invested heavily in circus infrastructure and artistry, constructing more circus buildings and opening more productions. Soviet circuses were also popular outside of the Soviet Union, where touring companies frequently outsold local circuses.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, instead of disbanding, Soyuzgostsirk reorganized into Russian Circus in 1992 and then in 1995 became the Russian State Circus Company, or Rosgoscirk (the spelling of the English transliteration varies), which continued to oversee the vast majority of circuses within the Russian Federation. The three-part mission of Rosgocirk is to “Keep the age-old tradition of the circus business, as a phenomenon of cultural heritage of the fatherland; create original and innovative rooms, attractions, and performances; and improve and develop the potential of circus arts—an integral part of the great Russian culture.”

Sergei Makarov, circus historian and the retired chief of Rosgscirk’s scientific section, notes that circus didn’t just transcend political change but also helped forge new international bonds after the USSR separated into different countries: “By integrating a circus program with artists of different nationalities, domestic circus became the spokesman of the international unity of people, a symbol of the close relationship of representatives of states of the former Soviet Union. This is a sign of modern unifying tendencies in the world’s global processes.” He claims circus unifies across other differences also: “Psychologically and spiritually, circus consolidates people of various ages, social classes, and ethnic groups, regardless of education level of individual culture.” Circus is a unifying force, and yet Russian circus is still considered an important part of the nation’s intangible cultural heritage. “Russian art,” explains Makarov, “remains true to the classic cultural and aesthetic ideals and traditions.”

Moto-Hippo Kislovodsk

Today, Rosgoscirk, is a “unique creative and operational complex” of more than permanent and traveling circuses, with separate management teams overseeing stage shows, ice shows, water shows, midget circuses, revues, marine animals, bizarre attractions, and other sub-categories. Rosgoscirk employs 2,000 performers and 7,000 other workers in 42 permanent buildings, approximately 30 traveling shows, and 53 other properties including Centers for Circus Arts in Moscow and Rostov-on-Don and a circus factory in Moscow that manufactures props, costumes, and equipment. The company also owns over 2,000 animals representing 140 species.

When the communist circus agency Soyuzgostsirk incorporated into Russian Circus, only four circuses chose to privatize instead of joining the national company: Great Moscow Circus, Nikulin Circus, St. Petersburg Circus, and the Kazan State Circus. Although these four companies are separate entities that are not included in the Rosgoscirk system and instead are directly subordinate to the Russian Ministry of Culture, they maintain close relationships with the conglomerate, both creatively and in business. Rosgoscirk provides them with acts and also includes their acts in its programs. A full performance of Nikulin Circus plays in the Rosgoscirk circus in Sevastopol. Plus, Rosgoscirk participates in all festivals produced by the independent circuses, and the directors of Nikulin and Bolshoi circuses are members of Rosgoscirk collegiums.

Although some observers credited the popularity of circus in the Soviet Union to its ability to serve, sometimes simultaneously, as both propaganda and escape from Soviet philosophy, circus was enormously popular before the Revolution and continues to be enormously popular in Russia today. Similarly, Rosgoscirk’s touring shows are still popular around the world, and the company works hard to maintain and develop relationships with its foreign business partners. Its biggest foreign partners in 2014 were Byelorussia, Kazakhstan, Japan, Peru, Ecuador, Columbia, Turkey, Mongolia, and China. Besides sending entire shows on tour, the company provides Russian circus artists as stand-alone acts for foreign circuses, for example Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey in the USA and Cirque du Soleil in Canada. CEO Vadim Gagloyev describes the international exchange of artists in almost philosophical terms: “The circus is still an art that knows no boundaries. It was always wandering, always crossing borders. Circus is always a journey. The condition of this profession is never to stand still. Therefore, the circus is very international. Many of our artists work for Cirque du Soleil and other shows around the world, and we have a lot of foreign artists working for us here in Russian, including Egyptians, Ukrainians, and performers from Central Asia.”

Masha Beschastnov: Happiness

This year, Rosgoscirk celebrates 95 years since Lenin’s proclamation established its precursor. The company is recognizing this milestone with a series of commemorative events, including a conference on the development of circus arts, a gala performance at Nikulin Moscow Circus, participation in Moscow’s International Military Music Festival and City Day celebrations, a photo exhibition on the history of the State Circus, a ceremony honoring veterans of circus art, and a nationwide circus festival in 34 cities. with many shows giving away free tickets to disadvantaged patrons.

Rosgoscirk doesn’t just give away tickets during its birthday year. Rather, it has a core mission of expanding access to circus performances to all audiences. “We know that we are a social orientation,” says Gagloyev. “We are not a commercial entity but a federal government enterprise. One of the main problems, sorry for the official language, is ensuring equal access to circus product. We have held down price growth, so our average ticket price is much lower than in Europe or Japan. … We have the ability to sell tickets cheaper … so we can work in small towns, and not only for millionaires, ensuring equal access to ideas.” In fact, he says, the company is willing to lose money to ensure access: “We can go on damages deliberately, knowing that the outcome should still get a plus.”

In September, Gagloyev announced that all branches should work to achieve self sufficiency by 2020, which he said will necessitate “ambitious but feasible” earnings growth and expense reductions. Already this change is underway. In 2013 Rosgoscirk received 1,200,000 rubles in state subsidies; in 2014 that figure fell to 800,000. Gagloyev says that reducing dependence on the state will allow the Russian State Circus company to focus on overhauling the branches and developing the industry as a whole instead of on subsidizing individual circuses.

In 2014, Rosgoscirk created a three-year road map for capital repairs and reconstruction of existing circuses throughout the country. In particular, Gagloyev hopes the renovations will bring new technology to the existing buildings, as he worries that outdated technology is causing Russian circus to lose its preeminence in the international circus world. All state funding will be spent on modernization of buildings that haven’t been repaired since the 1970s. Two circus buildings (Ivanovo and Tula) were repaired in 2014 and three more (Chelyabinsk, Ryazan, and Nizhny Tagil) are scheduled for renovation in 2015. Many of the old buildings are built in glass and concrete in the Soviet era style, but some have historic or aesthetic significance. Built in the form of a tractor, the circus building in Krasnodar is a Soviet constructivist landmark while the circus-theater in Rostov-on-Don circus is considered such a monument of culture that guests arrive in evening clothes. Of course some Russian buildings pre-date communism altogether. The recently rebuilt Saratov circus celebrated its 140th anniversary in 2013. Founded by the Nikitin Brothers, it was the first stationary circus in the country.

After fixing existing infrastructure, the company may start to expand circus to new regions, including Ulyanovsk, the North Caucasus, or a “vast empty space” between Irkutsk and Vladivostok called Nepahannoe field. It also plans to reach out to new international partners, especially in Latin America and Asia, according to Slava Sedov, chief public relations officer. Gagloyev says he is negotiating with partners from China, Turkey, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates and in conversations with potential partners is Chile, Brazil, and Mexico. Over a decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the company is seriously re-examining its outdated foreign contracts and working to create sustainable partnerships going forward.

In addition to updating the buildings, Gagloyev is ready to update the artistic presentation, partly to compete with relative newcomers like the 30-year-old Cirque du Soleil and partly to attract younger audiences within Russia. The new Russian circus, he says, “will fit all genres and directions. I think our chances are limited only by our imagination. I have an idea in general to vary the circus genre as a synthesis of other art forms. … Gediminas Taranda came up with the idea of the play, which would be attended simultaneously as ballet, opera, and circus.”

Makarov agrees with Gagloyev that Russian circus will have to fight vigorously to survive in difficult economic conditions but is confident that the “love of spectators and reliable support from the state” will see Rosgoscirk through any tough times. In fact, he argues, “in modern conditions of societal transformation, the value of circus arts is further increased. Circus is the bearer of traditional values and an educator of new generations of viewers in the spirit of humanism. Circus bears enormous positive potential emotional impact on the audience.”

Gagloyev cites one competitive advantage the company has in its tour negotiations: it is one of the few companies left that offer animal acts: “You know, it’s a powerful competitive advantage, because not all circuses have animals today. Firstly, it is expensive, and secondly, there is a political component.” He explains how much work it is to maintain the animals well and train them humanely. Interestingly, while Rosgoscirk owns and represents the animals, many of them come from private circuses with family dynasties that have worked with animals for generations. “We know the case when the baby cub lives in a trainer’s family,” says Gagloyev, “he becomes a pet, like a cat.”

Sedov summarizes the role and significance of this 95-year-old organization in the context of the modern, global circus: “Rosgoscirk is the biggest circus organization in the world that provides traditional and modern performances. In Russia we implement a social mission by artificially holding prices low so that an average family could come and have joy. Internationally, we provide highly artistic and fantastic shows so that spectators may have an opportunity to get acquainted with a world-famous part of the Russian culture.” Director Gagloyev agrees: “Our company is a national treasure.”

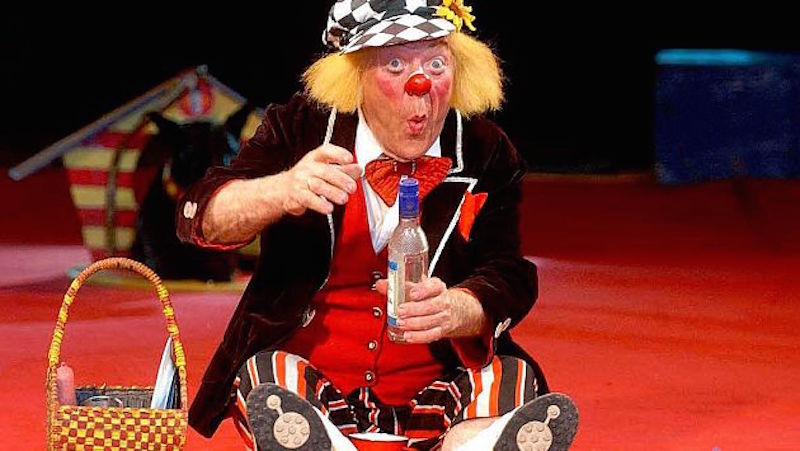

Special thanks to Slava Sedov, Chief, Public Relations Office Rosgoscirk, and Ivan Vlasov for their assistance in the preparation of this article. circus.ru Featured Image: Oleg Popov

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!