Is Music The Language Of Connection?

Scientific studies have shown that many effects of music can be seen in the brain. Multiple observations have demonstrated some interesting findings on the bodies and minds of listeners and performers alike, leading to the question: “Is music the language of connection?”

Group Singing and Emotional State

Group singing is one such area that has been studied; results showed that participants benefited from feeling calm and experienced an elevated mood and the release of bonding hormones, with effects that could be likened to the results of meditation. Additionally, scientists from Berkeley found that on top of the mental benefits we already know music can bring, there are social and physical effects on singers, such as feeling emotionally close to others, and a reduction in physical pain: “Results showed that feelings of inclusion, connectivity, positive affect, and measures of endorphin release all increased across singing rehearsals and that the influence of group singing was comparable for pain thresholds in the large versus small group context.”

As far back as the Hippocratic philosophy in Ancient Greece, art therapy was used in the treatment of illness and in “the improvement of human behaviour.” The use of art therapy does seem to be experiencing something of a resurgence in some areas today in the treatment of children, notably in adults with dementia. In the UK, there have been initiatives gaining popularity in this field, such as the Alzheimer’s Society’s “Singing for the Brain” campaign, whose community choir brings people together to participate in music. They explain: “Evidence shows that music can help improve and support mood, alertness, and engagement of people with dementia, with research* showing that musical memory is often retained when other memories are lost; music can help people to recall memories due to the nature of preserved memory for song and music in the brain.”

Understanding that singing is a universal tool that can be beneficial to memory, mood, breathing, posture, and muscle tension, and creates a sense of well-being and connection, surely we have to question why we are not placing more importance on this relatively simple activity. And while using music therapy for the sick is commendable, why are we waiting until someone is unwell to implement it, rather than using it as prevention and sustenance?

In UK schools, the opportunity to study music history and participate in performances, creative compositional activities, and learn an instrument are becoming increasingly elite pursuits. The denial of access to music for every child in state school seems to be the ongoing initiative of the current government. Some private schools are even taking it upon themselves to share their resources, opening the doors of their concert halls to the local state sector. Warwick School in England is one such institution that has kindly offered education support to local schools through Warwickshire Music Hub. The reporting in The Big Issue explained:

“The facilities in Warwick are exceptional: there are many music teachers beavering away with nothing but a bunch of ukuleles. The contrast in music resources can be stark. The recently updated National Plan for Music Education (NPME) places much of the responsibility for delivery on individual organisations through the hub system that was created when the NPME was unfurled in 2011. Luckily, there are those who are taking the initiative, despite government indifference.”

It bears repeating that if we know there are such huge benefits to the brain, body, and spirit from music, and we use it as an actual treatment for the sick, it feels unethical to consciously withhold this from some select members of our society.

Enjoyment and Synchronization

A 2020 study in the journal NeuroImage observed that when audiences listened to a musical performance and enjoyed it, the brain activity of the performer and the perceiver synchronized together. Additionally, I found it interesting that the paper referenced several studies that had come before: “Previous neuroimaging studies also found that brain-to-brain synchronization is involved in behavioral synchrony, emotional contagion, and verbal/nonverbal communication. In general, interpersonal neural synchronization might be the neural basis of synchronized movement, emotional resonance, and shared understanding (Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2019).”

This took me back to watching a pub gig in a country where I’m proficient in around ten words of the language. As the singer worked the crowd, getting every one of us to clap and sing along, taking a line here, and a hook there on the mic, it soon became very apparent that not only was I, not a native speaker, present, but there was also a deaf lady in the audience.

What happened next was a rallying of forging connections through the music: the singer adapted what he could to include everybody, not only pulling out an Elvis number in English for me to join in, but by “signing” with gestures to describe the lyrics, employing the deaf lady’s partner to interpret here and there, and by taking her hand to feel the vibrations as he sang to her.

As we applauded her (in sign language, this is like the “jazz hands” motion, with the arms up at a 90-degree angle), she looked around at us and fought back tears of happiness. After the show, we couldn’t address each other with words, but shared a knowing smile, and a moment to acknowledge and appreciate the connection created by the language of music.

The Brains of Co-Creators

After skimming the surface of the studies and pondering the many emotional ramifications of musical connection, I began to wonder what happens to the brain when we create music together. Band and musical working relationships are often emotionally charged, but is the creative relationship measurably different scientifically?

If we know that “trauma bonding” exists, then what happens when we experience something intense, but mostly positive with another, where we make something tangible together out of nothing but our feelings? It is my suspicion that while we can feel everything on the spectrum from happy and free, to cold indifference, to hoping karma rains down on some past relationships, the connection between co-creators is a unique one, unlike any bond we have with an old friend, lover, or colleague.

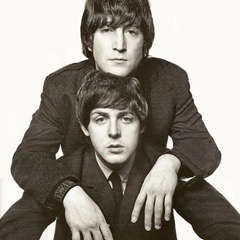

The day he died, John Lennon gave an interview speaking fondly of Paul McCartney. The pair had actually reconciled by 1976, despite their explosive disbanding six years earlier. John had said: “He’s like a brother. I love him. Families … certainly have our ups and downs and our quarrels. But at the end of the day when it’s all said and done, I would do anything for him. I think he would do anything for me.” — 8 December 1980 interview with Dave Sholin

It was clear there was still a great connection between the two, and the last time the pair met in person, Lennon’s parting words to McCartney were, “Think about me every now and then, old friend.”

It’s a pattern that can be seen throughout the music world – Stevie Van Zandt speaks of his brotherly friendship with Bruce Springsteen in his autobiography, stating that despite separating and uniting musically several times over the years, they only had three real arguments. With a lack of bitterness, and more of a “Eh, what you gonna do?” laissez-faire attitude in the book’s tone, Van Zandt’s affection for Springsteen shines through.

It’s funny how when the music stops and time rolls on, it doesn’t matter whether life took you in different directions, you simply grew up or had the mother of all disbanding experiences—the bonds run deep. We can be separate from our music friends for years and still cheer for them from afar when they meet a nice partner and find happiness, and it can feel like a punch to the gut when we hear hard times have befallen them.

If our brains literally synchronize, and we feel a measurable connection in a musical environment, and these memories will be the last to go, then perhaps the supposition that there’s more to it isn’t completely unscientific. The often-quoted man of science Carl Sagan once said, “For small creatures such as we, the vastness is bearable only through love.” It’s something I think about every now and then.

This article was originally published on TheatreArtLife.com.

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!