Everywhere and Nowhere: the New Wave of Site-Specific Circus

Typically, talking about site-specific circus means talking about a large outdoor space that’s converted (with, say, scaffolding or cranes or ladders or some such) to meet the technical demands of aerial work. We’ve all seen it. Off-the-top-of-my-head examples of this might include Montréal Completement Cirque’s stalwart outdoor show Minutes, or Aquanauts, a show by Cirkus Cirkör staged in a river, which recently headlined The Stockholm Culture Festival. These works are usually large scale, often spectacular in the true meaning of the word.

But there’s a new breed of site-specific circus designed to be performed in the most intimate of venues: a living room.

The Anti-white Cube

First, let’s break down a bit of context here. Site-specific work originally rose from the ashes of minimalism in the 1960s and 70s, and quickly gained a swath of devotees across disciplines: from art to dance to theatre to opera to acrobatics. The key thing about site-specificity is that the work is bound by the height, length, texture, and shape of walls or rooms; the scale or proportion of buildings; existing lighting conditions; ventilation; traffic patterns and so forth.

In other words, by their very nature these performance spaces are not blank slates, they come with their own history, function and structural limitations. The work, if executed well, becomes a conversation between the performance elements and the constraints and opportunities of the environment.

There are successful examples of site-specific work in every discipline. But that’s not to say there aren’t detractors of this practice, especially when used gratuitously or for no apparent reason.

A couple of months ago, Siobhan Burke, dance critic of the New York Times, tweeted: “Unpopular opinion? performing in a space doesn’t necessarily “activate” the space.”

Burn. But true enough.

Responses on Twitter ranged from the nonplussed (“Why is that unpopular?”) to the bemused (“It is certainly over promised lol, and sometimes promised and not even attempted.”) to the nuanced (“Sometimes the performance fights against the space (and makes things difficult for everyone).”) to the cynical (“Not unpopular. Corny, non-concept from the start.”).

One thing is clear; placemaking, site-activation, site-specificity, whatever you want to call it, is a contentious issue. It needs to be done right or not done at all. But it’s gaining ground in circus circles around the world, especially as a kind of reaction against the glitzy high production values of mainstream circus productions in large theatres andchapiteau.

New-wave Site-specificity

One proponent of performance work in residential spaces is French collective Hors Lit. Literally translated as “Out of bed,” Hors Lit has been running since 2005, presenting iterations in major cities across Europe.

The principle of Hors Lit is simple: four artists of various disciplines each prepare an act in an apartment made available for the run of the show. The artists rarely have more than a month to prepare their project, the length of which does not exceed 20 minutes. Come performance time, the spectators, restricted to smallish groups, will gather at an address given to them when they booked their tickets, and from there they move from one apartment to another; from one artistic act onto the next.

The core principle underlying the work of Hors Lit seems to be the fragility of the interaction established between the artist and the public. For the artists presenting work within the context of Hors Lit, it’s an opportunity to try different things. Some take this opportunity to test a collaboration or a concept, hoping to plant a seed of expression for further development in another context.

And from a Living Room in Montréal…

Another champion of highly intimate site-specific performance is Montréal-based circus artist Claudel Doucet. Since graduating from École Nationale de Cirque in 2004, she has carved out an impressive professional career touring as a contortionist and aerialist for Cirque du Soleil and Circus Monti and spent several years performing cabaret in Germany.

Now, Doucet is pivoting from performer to director, and has a couple of independent projects under her belt already.

Key to Doucet’s ongoing artistic research are the twin concepts of intimacy and proximity. To explore these ideas, Doucet has created work in unconventional performance spaces including libraries, schools, universities and the Montréal metro.

“I want people to see circus on a really human scale.” she says, explaining that she wants the audience to see performers as real people, not superhumans doing tricks from a distance under fancy lighting conditions.

Last year Doucet mounted an ambitious project in a Montréal high school library. “I got this tiny little grant and I went full Hollywood” she says.

Her extravagant vision for that project meant that she wound up working around the clock to pull the piece together, but she was happy with the result. “I really enjoyed changing the paradigm of how we do things, especially in the sense of who it welcomes (into the space).”

For her next project, she deliberately set out to create something on a more modest scale, in part to preserve her own sanity.

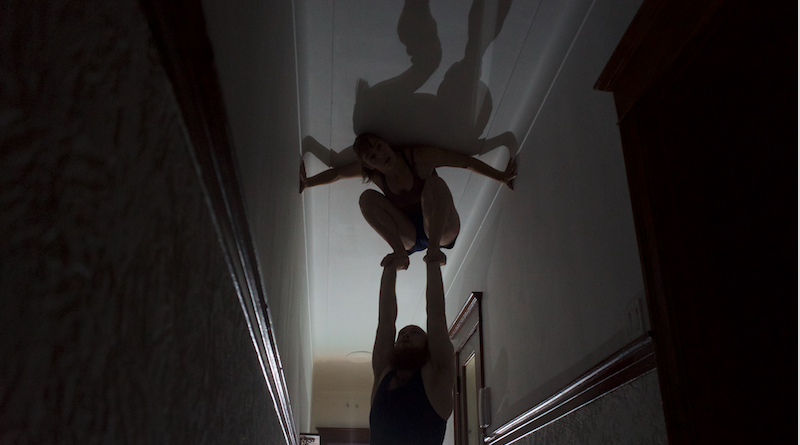

Her concept? To create an acrobatic show in her apartment. The piece, called Se prendre, is currently in development, having been kick-started by a residency in Montréal over the summer of 2018.

At its core, Se prendre is an essay on intimate relationships, and the complexity of our attachments. The work is driven by interaction between the performers, the space and the audience: what the marketing blurb calls the “precarious cathedral of simultaneous existences.”

In some ways, Se prendre can be seen as a rebellion against the aesthetic and canon of Montréal circus. Think of it as a palate cleanser, says Doucet.

Site-specific work calls for a kind of oulipian restraint, not unlike the French novelist who wrote an entire novel without using the letter “e.” There are obvious restrictions of space and lighting at play, but perhaps those restraints can be artistically freeing, or at least challenging in the right ways. Apartments are not the place to bust out a trapeze or, say, an equestrian act. So what kind of circus are we talking here?

For Se prendre, Doucet and her fellow acrobat Cooper Lee Smith have developed a highly personal acrobatic language that uses the space in innovative ways and acknowledges the shared risk and responsibility of the experience. Doucet and Smith (also a graduate of ENC) work with dramaturge Félix-Antoine Boutin and space designer Étienne René-Contant to fit the work to the space and explore its possibilities.

Together they are reaching for an answer to the question of what happens between the spectator and performer when put against a residential backdrop. So what does happen?

Doucet notes that the codes inevitably shift, for a start. The eyelines change. The performers can sense the audiences’ reactions in real time – resulting in (hopefully) a destabilizing, honest exchange, although the performers never look at the audience, but conduct their intimate exchanges as if alone.

In some ways, Se prendre can be seen as a rebellion against the aesthetic and canon of Montréal circus. Think of it as a palate cleanser, says Doucet; “For the audience it can be a really refreshing experience…. A surprise experience hopefully.”

In some ways, Se prendre can be seen as a rebellion against the aesthetic and canon of Montréal circus. Think of it as a palate cleanser, says Doucet; “For the audience it can be a really refreshing experience…. A surprise experience hopefully.”

Accessibility and the idea of arts-for-all is also a leading concern for Doucet, who would like to take the work to communities that might not otherwise have opportunities to see circus.“(We’d like to) go to small town communities, villages… whole countries have no festivals or institutions that mandate circus projects so I’m hoping we can cross those limitations.”

This is not to say that the artistic team is tied to the idea of self-producing small-scale tours to tiny towns in the middle of nowhere. The work is already slated for a May premiere in a major European festival (to be announced shortly), followed by a season in Montréal.

Despite the fact that ticket sales will be small due to the limited space; “I feel this is a really great project for festivals, because the kind of venue it needs is very easy to add to a programme,” she says.

The Disadvantages

I ask about the drawbacks to working in unconventional spaces; licensing, zoning, insurance, health and safety – all of which Doucet calls a “legal puzzle” – as well as the other obvious constraint of seating. Doucet has had to think carefully about audience size to ensureSe prendre is a comfortable and engaging experience for everyone involved.

“So far we’ve gauged that we need a certain square footage: half a square metre per person.” she says, laughing. “We’ve tested (an audience of) up to 13 people – accidentally! But obviously it will depend on the space we’re working in.”

Next Steps

Se prendre is currently still in development; the team has completed one creation residency and the work will be showcased as it currently stands in Montréal’s networking showcase, OFF-CINARS, this November. This biennial event will provide presenters (usually some 370 of them from all over the world) the opportunity to seeSe prendre and consider programming it for their festivals and venues.

It’s almost the opposite thing to site-specific. It’s site-agnostic. Doucet likens it to the old model of the traveling circus show; having the ability to add a performance to a festival program without needing a special venue or equipment provided.

Meanwhile, Doucet has already lined up two more residencies to refine and develop the work over this Northern Hemisphere winter and spring. The residency venues include a house in New Zealand, a loft space in Iceland, and an apartment in Toulouse.

I ask Doucet about her process to adapt the piece from venue to venue.“Regarding the process to adapt, we only have “untested” hypothesis. Firstly, we provide a form of technical rider and discuss with the programmers what are the opportunities and constraints of our work. We ask that they give us a video tour of the apartment so we can prepare. We have a “show kit” that is adaptable. We carry a number of options regarding sounds, lights, etc. We request a minimum of three days before the premiere for set up and adaptation.”

“We have a certain amount of scenes and we will try to keep them in the “original” room where they were created (eg: living room first scene). We have a few “swing scenes” which can either happen or not happen. They are like satellite scenes and transitions that add to the narrative line but are not essential to the core of the piece. We have to arrange the scenes regarding which rooms fit the feeling and needs of each. We also have to take into consideration the movement of the audience in a fluid way across the space. Their comfort and visibility is also always a priority. We stay open to create completely new material if the space inspires us.”

In this way, the work is designed to be adaptable, portable, entirely nomadic. It’s almost the opposite thing to site-specific. It’s site-agnostic. Doucet likens it to the old model of the traveling circus show; having the ability to add a performance to a festival program without needing a special venue or equipment provided.

But for Doucet and her team, the work will remain true to its artistic concerns, wherever in the world it finds an audience.

“I want to access people’s vulnerability… the traditional codes are broken and we get to rewrite those codes. Together.”

All photos courtesy of Guillaume Langlois

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!