Circus for Change-Equity and Inclusion in Circus Questionnaire-North American Results

Abstract

To examine how Circus broadly approaches equity and inclusion in North America, a survey was generated and distributed online. Respondents answered questions across categories of comfort, diversity, bias, professional experience and expertise, and demographics to gauge whether significant differences in subjective personal experience existed between artists. The data was then collated, analyzed, visualized, and displayed. Respondents indicated significant differences in experiences when it came to categories of bias, diversity, and grants/scholarships but little difference in professional and comfort categories. Open ended questions indicated a desire for more inclusive policies in circus spaces, inclusion of “sliding-scale” and other alternative payment options, a larger number of people of color in executive positions, elimination of hiring biases, and higher levels of racial equity training for circus staff and students.

Introduction

Circus has been a staple of American Entertainment since its founding. Indeed, digital databases likeCircus in America: 1793-1940 catalogue the wide array of circus acts through American history and how they are influenced by the zeitgeist of the world in which they are performed. Through these primary sources, it is clear that circus is a “microcosm of society,” complete with the complexities of the settings in which it is performed. From the side show to the use of animals, the circus has evolved with people’s tastes and tolerances. It has reflected society’s attitudes toward entertainment, comedy, race, class, ethnicity, and the unknown.

In light of increased national focus on racial justice and the public lens on institutional racism, it is an important time to take the temperature of circus’ role in these systems. Circus has often been trumpeted as the “paragon of inclusion”. Indeed, the idea that anyone “can run away to join the circus” implies that the institution is for everyone. However, to date, there has been no authoritative study that addresses whether this maxim holds weight. So in conjunction with numerous organizations and with the help of the circus community, a questionnaire was created to evaluate circus artists’ experiences around race, equity, and inclusion. It was distributed digitally across North America over the summer of 2020 and interrogated demographics, resource distribution, opportunity, and bias among circus individuals. The questionnaire had an overarching goal to attain a big picture of potential equity issues in circus spaces using data over assumption.

Recognition of Imperfections

This research is intended primarily to be a jumping off point for future anti-racist and inclusivity work. It attempts to coalesce a broad range of perspectives and experiences, and while it strives to avoid generalizations and oversimplifications, it is inevitable that they will pop up. By no means is this intended to be a prescriptive document, but instead as a tool to understand the circus community more fully, drawing back the curtain on both its strengths and defects. That said, the data below will be useful in cataloging the “State of Circus” today and advocating for resource distribution where it is needed, highlighting facets of privilege and exclusion specific to circus, and promoting advocacy.

Methods

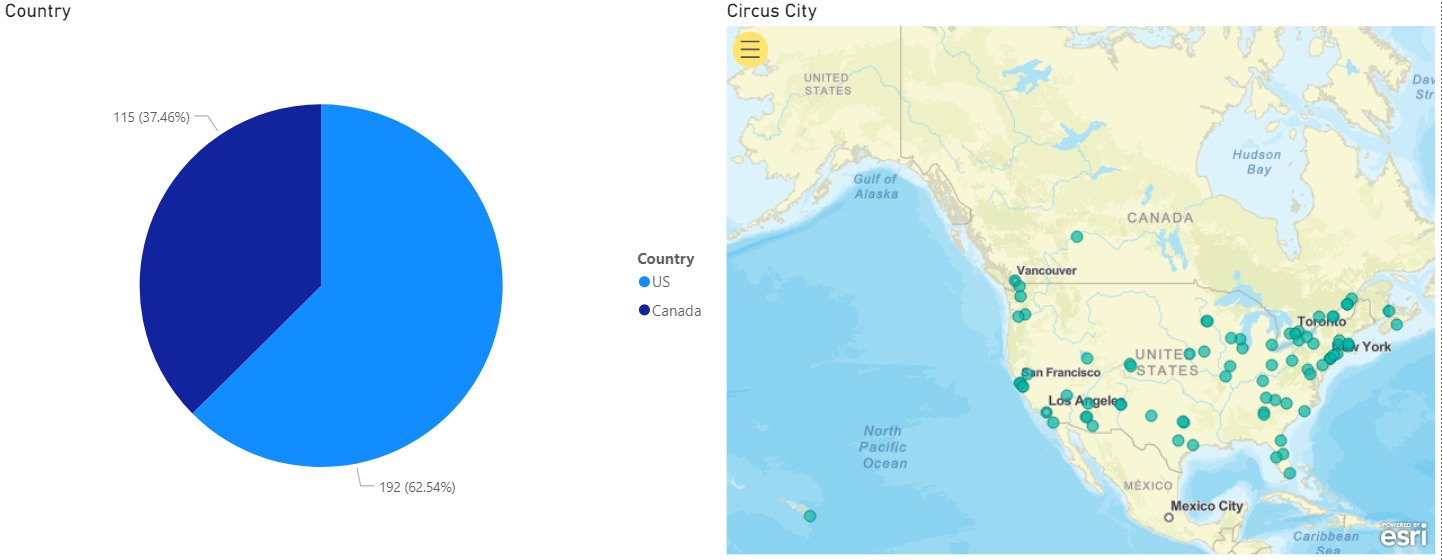

307 participants volunteered to respond, 115 from Canada and 192 from the United States. Participants were selected online via social media, including Instagram and the “Circus Every Pandemic” Facebook group, and through promotion by ACE, CircusTalk, CSAW, and EnPiste – National Circus Arts Alliance. Participation was on a voluntary basis, and respondents represented a “convenience sample” of the Circus community.

Participants were encouraged but not required to share demographics information. Data from participants from outside North America was excluded as it was beyond the scope of this Questionnaire.

Participants completed a two-page Questionnaire compiled on Google Docs. The questionnaire was assembled in collaboration with the aforementioned circus institutions and used a framework from “Teaching Tolerance” source materials. The questionnaire was designed to measure individual experiences of inclusion and bias in the circus community with an emphasis on experiences informed by race and ethnicity. The questionnaire was also designed to determine whether sufficient resources are available universally regardless of location.

The questionnaire contained 40 questions, and a sample of questions can be found in the Appendix. Questions were categorized in the following labels: Professional, Expertise, Grants/Scholarships, Diversity, Comfort, and Bias. Questions could be answered on a scale of 1-5, where 1 signified the participant “Strongly Disagreed” and 5 signified the participant “Strongly Agreed” with a given option. The median of each response was obtained for each question among groups.

Courtesy of EnPiste, the questionnaire was translated to French and distributed through Quebec. Responses were then translated back to English.

Participants generally completed the questionnaire within 10 minutes. Participants were then thanked for their participation, and were informed that results would be published anonymously and that sensitive information would be kept private.

Results

Around 62% of respondents live in the United States while 38% live in Canada.

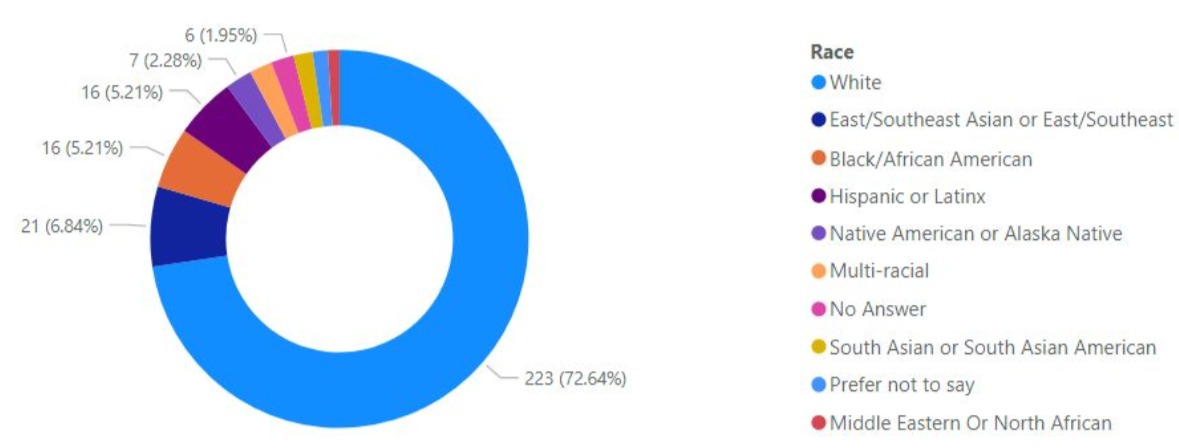

Respondents self identified as East/Southeast Asian (6.8%), Black/African American (5.2%), Hispanic/Latinx (5.2%), Native American/Alaska Native (2.3%), Multiracial (2.3%), South Asian (2%), and Middle Eastern/North African (1%).

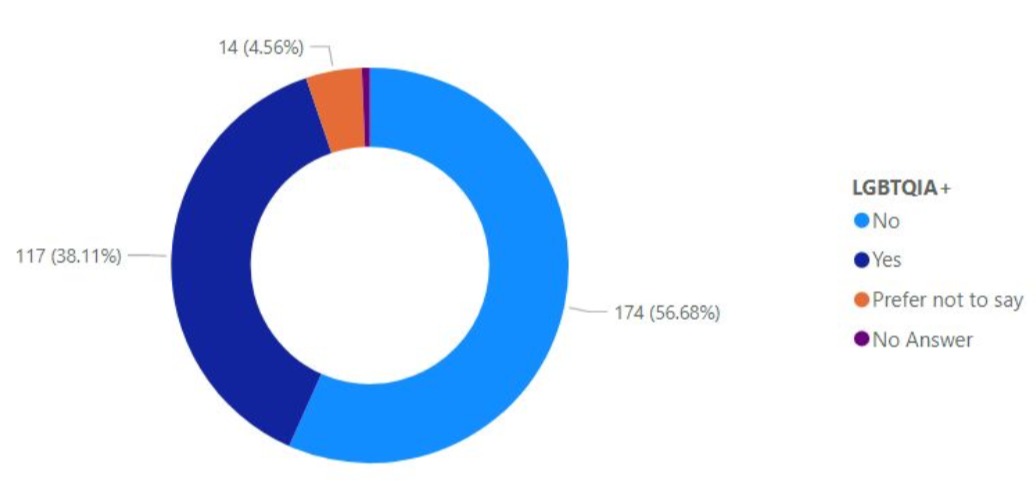

The majority of respondents identified as white (72.6%), and heterosexual (56.7%). However, a significant number of respondents identified as LGBTQIA+ (38.1%).

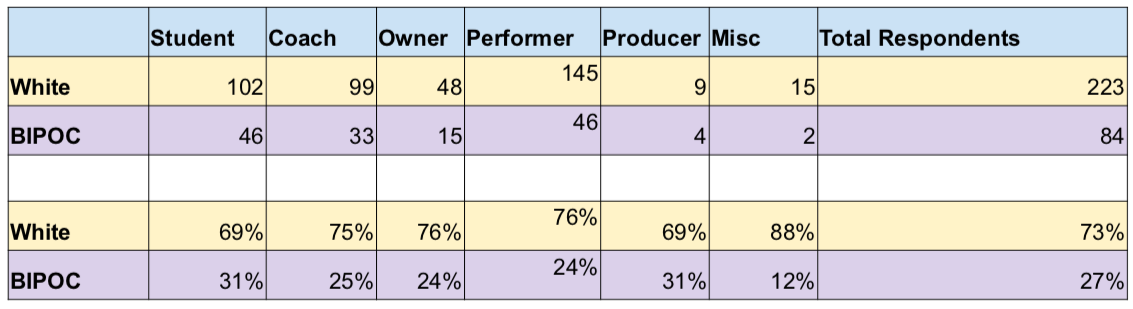

Many respondents identified across roles. 64% identified as Performers, 50% Students, 44% Coaches, 21% Owners, 5% Miscellaneous, 4% Producers, and <1% as Parents. While there are fewer BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) respondents, there was no significant statistical difference between the circus roles of white and BIPOC respondents, though there was a slightly higher quantity of white circus owners and performers (+3%).

Due to the number of participants answering the questionnaire, in order to find statistical significance, responses were compared between those who identified as white (223) and those who did not (84). While this approach has limitations and groups individuals in comparison to a “white” baseline, those who organized the study still believe this data could be of use. For the following questions, participants will be grouped in these categories, though it will fail to express the full range of experiences. Please refer to the Discussion section and the Appendix for firsthand responses around these categories.

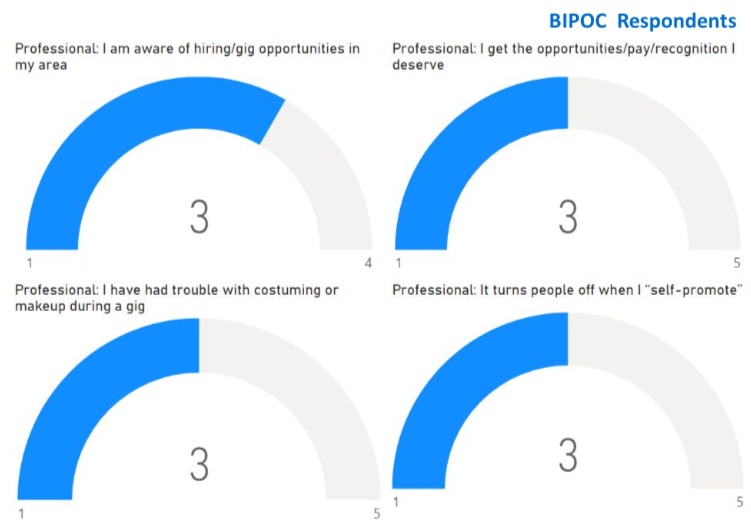

Figure 5: Professional Category Median Answers

Within the “Professional” category, the median of all responses was 3 (Neither Agree nor Disagree) and there was no difference between the two categories of respondents.

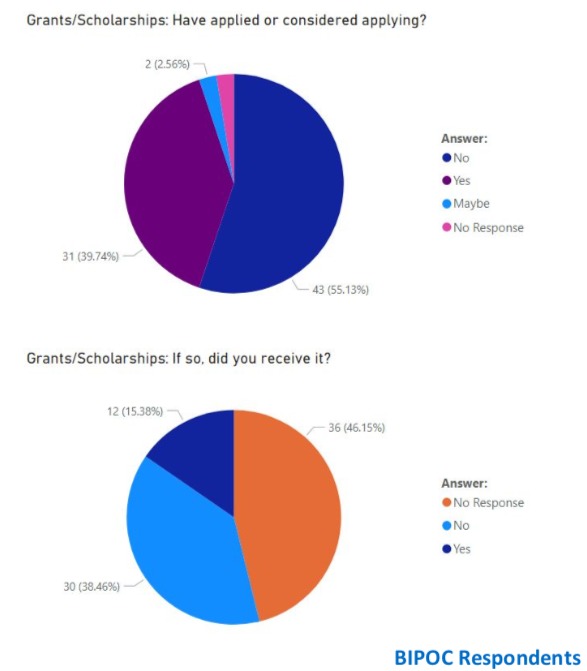

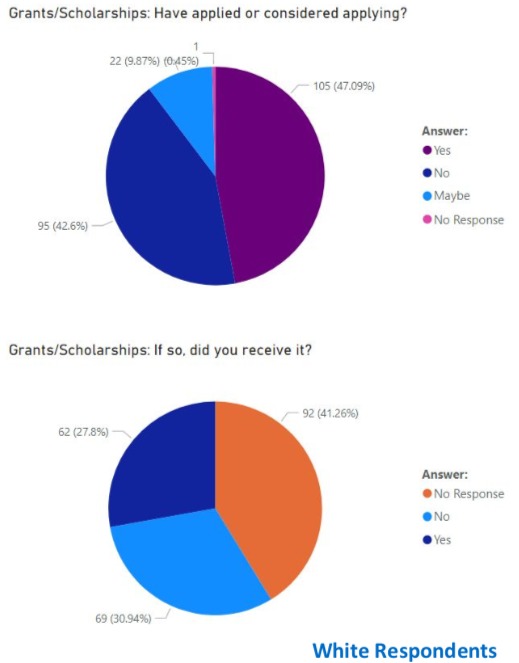

Figure 6: Grant/Scholarship Category Median Answers

In terms of Grants and Scholarships, out of the 47% of white Respondents who have applied for Grants and/or Scholarship opportunities, 28% have received them. Out of 40% of BIPOC Respondents who have applied for Grants and/or Scholarship opportunities, only 15% have received them.

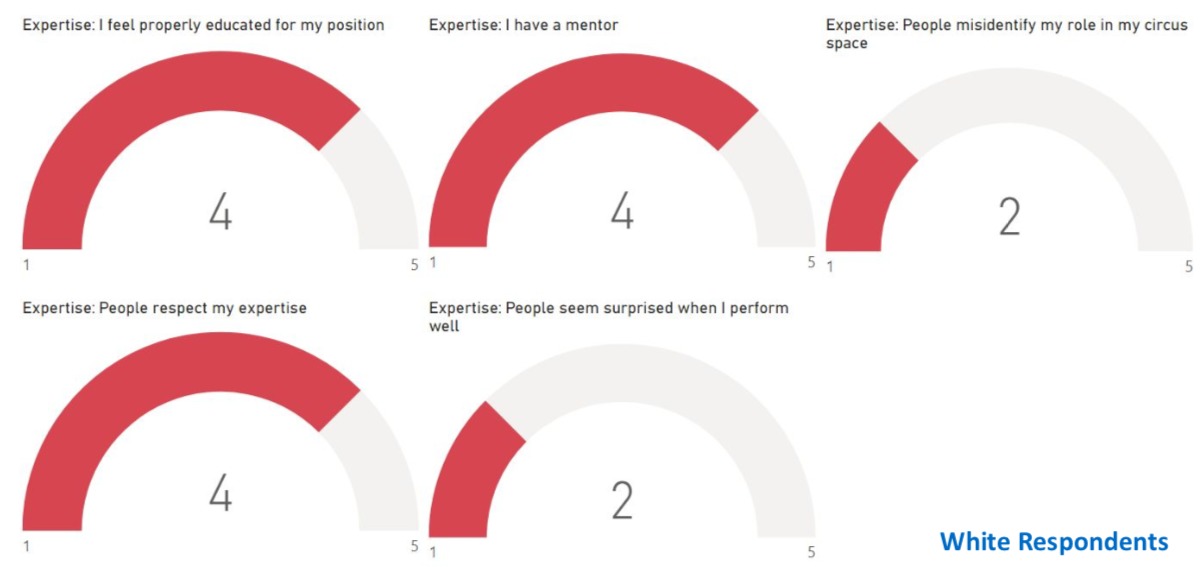

Figure 7: Expertise Category Median Answers

The “Expertise” category saw no change in most questions but one (a 3 compared to a 2): that “people seem surprised when they perform well.”

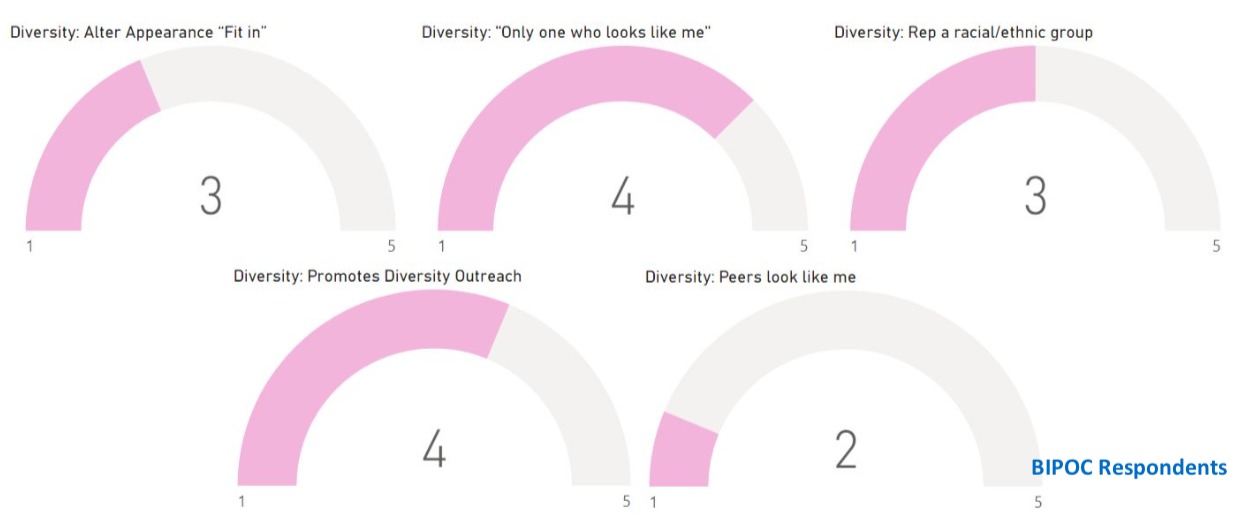

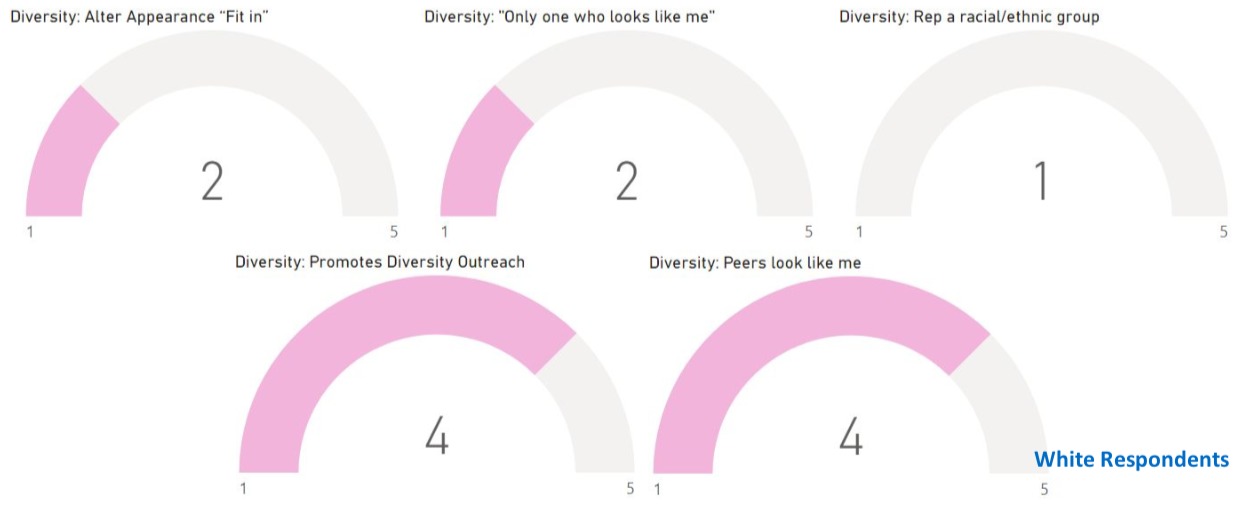

Figure 8: Diversity Category Median Answers

The “Diversity” question represented the largest difference between groups. BIPOC Respondents scored higher (agreed more) in altering appearance to “fit in”, being the only one who looks like them, feeling that they represent a certain racial/ethnic group, and scored lower (disagreed more) in having peers who look like them.

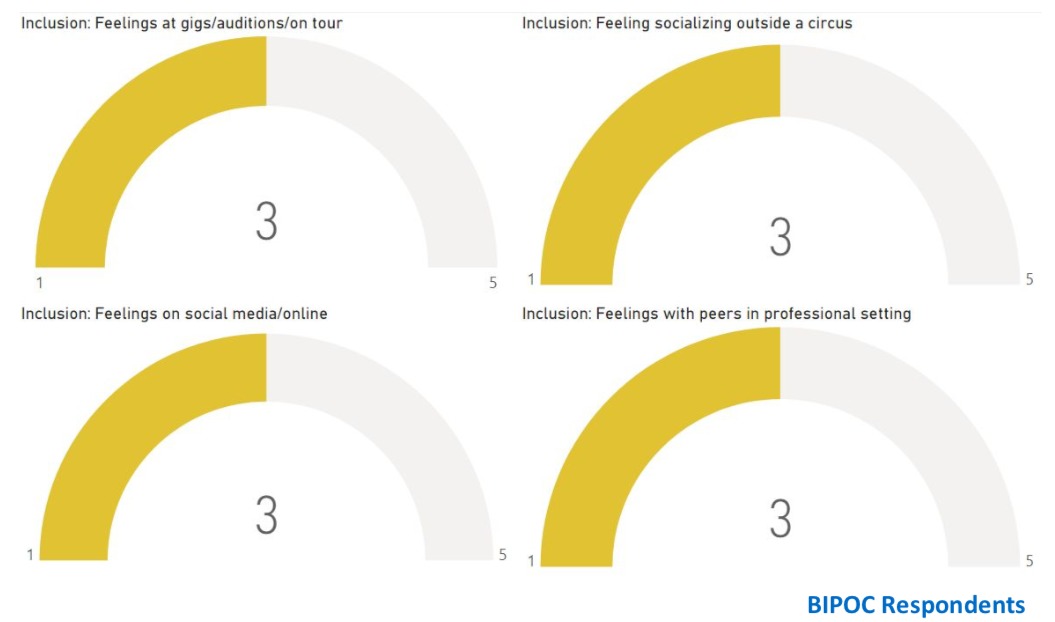

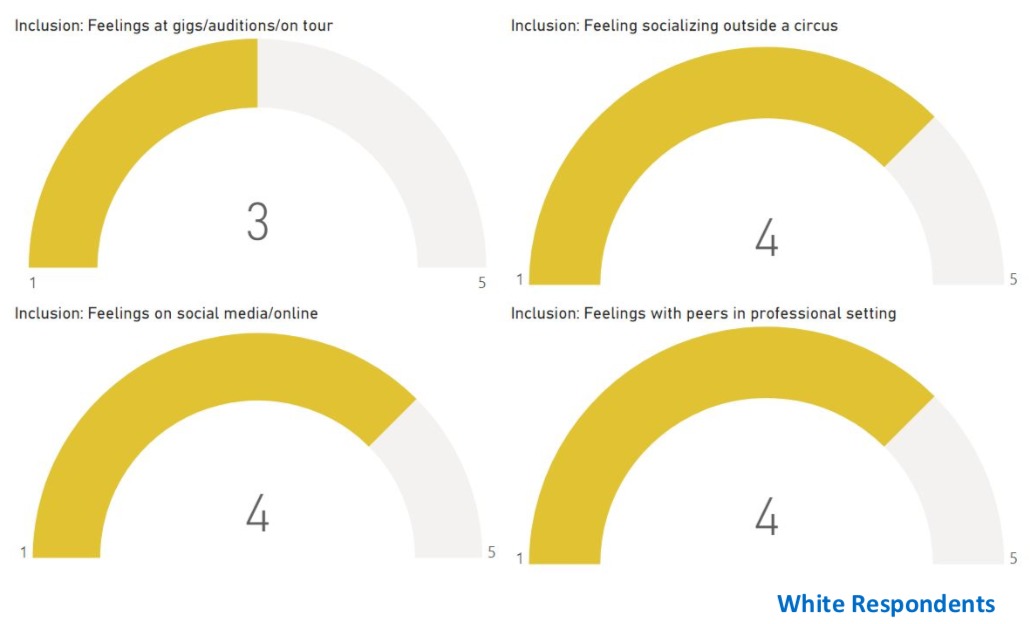

Figure 9: Diversity Median Answers II

BIPOC Respondents also scored lower in feelings of inclusion while socializing outside of circus, in social media, and with peers in a professional setting.

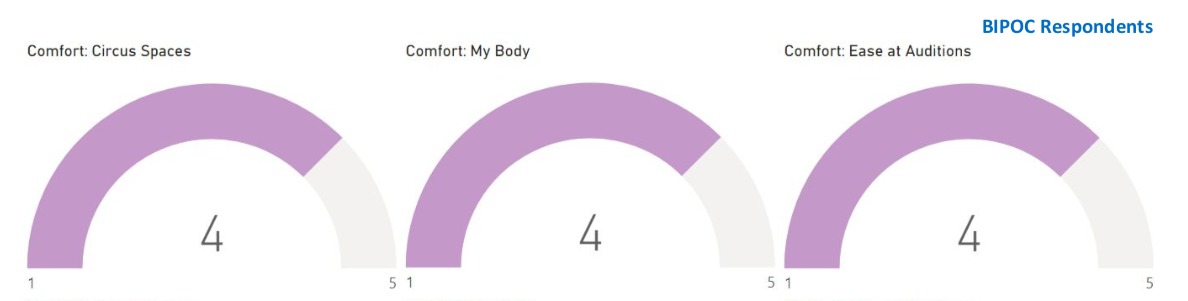

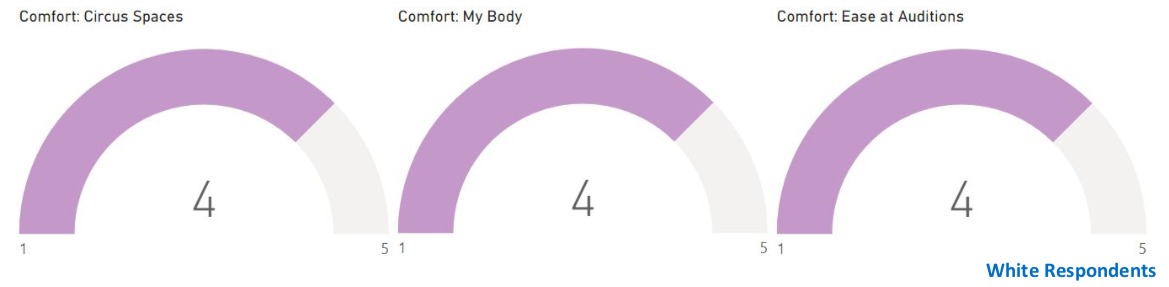

Figure 10: Comfort Category Median Answers

Regarding the “Comfort” category, the Questionnaire saw no change between groups, where the median response was 4 (Agree) for all questions.

Figure 11: Bias Category Median Answers

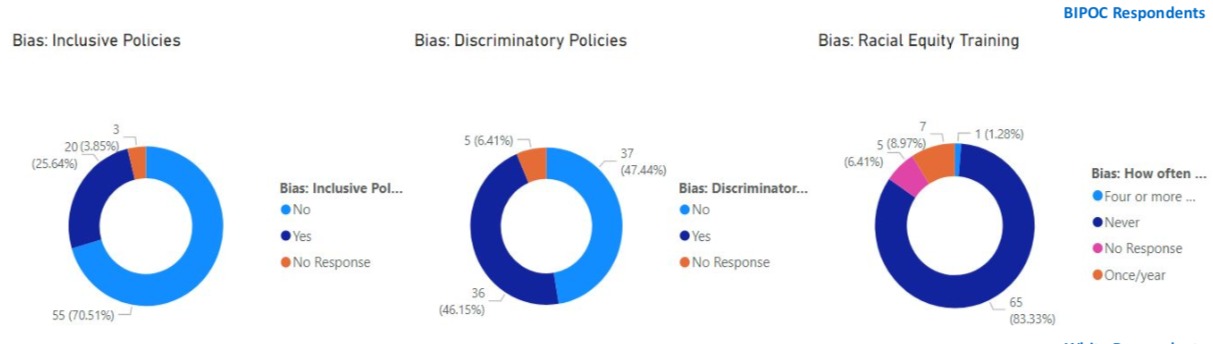

In terms of Bias, around 55% of white respondents perceive that there are no discriminatory policies at their institutions; however, a greater proportion of BIPOC respondents report a presence of discriminatory policies at their institutions. What is important to note is that a significant portion of all participants recognize a lack of inclusive policies in their circus spaces. Both groups’ responses align in that the majority agree there are no inclusive policies at their studio/performance space that are actively inclusive and prevent discrimination, and that their institution has never undergone racial equity training.

Qualitative Responses

With regards to qualitative comments, participants shared the following suggestions for the circus community as a whole. Comments are grouped by theme and ranked by the quantity of participants asking for change in these areas. The most popular requests are for providing financial assistance for artists, creating zero-tolerance policies for discriminatory language and behavior, promoting inclusive language, and creating programs for local outreach. Highlighted responses are included in the Discussion section.

| Comment theme | Comment Quantity |

| Low income scholarships/grants/sliding scale classes/workshops | 18 |

| No tolerance policy (or culture) for discriminatory language/behavior | 11 |

| Use of pronouns and/or other inclusive language, use of non-exclusive language | 10 |

| Local outreach (high schools, community, boys and girls club, special needs) | 10 |

| Active all body acceptance, class structure adaptable to body size, disability, et cetera | 9 |

| Diverse teacher or leadership base (active hiring policy) | 5 |

| Intentionally trying to market to BIPOC performers when casting for shows | 3 |

| Community/Staff Listening | 3 |

| Social Circus Outreach | 3 |

| Racial inclusivity training by BIPOC, direct work around inclusion/gender/sexuality | 2 |

| Work Trade Programs | 2 |

| Positive feedback/denouncing negativity towards students/performers | 2 |

| Performance opportunities for all levels/people | 2 |

| Staff meetings about inclusion | 2 |

| Payment plans to increase affordability | 2 |

| Attempt to balance gender ratios in performing | 2 |

| Modified structure of classes for multi-abled students | 1 |

| Financial transparency | 1 |

| Producer pay cuts | 1 |

| Providing free classes, paid for by donated teacher times/organization pays | 1 |

| Explicit invitation to include stories from diverse cultures when creating performances/cross cultural sharing during class | 1 |

| Non-gendered classes | 1 |

| Employees hired instead of contractors | 1 |

| Paid time for anti-racist education | 1 |

| POC only workshops | 1 |

| Inclusion survey for students | 1 |

| Actively reaching out to artists of color in creating/casting shows, using shows to promote and benefit organizations that bring more inclusivity to the community. | 1 |

| Quotas for different demographics | 1 |

| Code of ethics/guidelines against sexual harassment | 1 |

| Code of ethics/guidelines against discrimination | 1 |

Discussion

While this Questionnaire is by no means comprehensive and ideally would have a higher number of respondents across North America, survey results suggest the following note-worthy points:

- At a professional level, there is quantitative data indicating relative similarities between white and BIPOC aerialists in terms of reported difficulties with costuming, gig opportunities, and self-promotion. That said, a number of qualitative responses indicate that, across the board, costuming issues arise due to restrictions based around race/ethnicity and size/weight (with an emphasis on hiring thinner performers) which could skew the quantitative trend, and reveals a lack of inclusivity for BIPOC and white performers. Qualitative responses also indicate that there is, at the very least, a perceived trend of hiring primarily white, skinny, and typically female-presenting performers. “Typecasting” or “hiring for a look” was mentioned 40 times across all respondents’ comments.

- The creation of further philanthropic bodies aimed at awarding grants for BIPOC performers and increasing award rates for applicants for financial support. Interventions at early stages in circus education would further increase equity.

- While many mentioned that circus can be “prohibitively expensive,” they also mentioned ways circus institutions have made steps to tackle this barrier to entry: incremental payment plans, work/study programs, sliding scales, or options to use methods of payment outside cash apps or credit cards.

- While participants self-selected this survey clearly focused on inclusion and equity, the quantitative responses do indicate that there is a clear perceived need for active inclusion policies in studios and training spaces. Actual solutions will likely reflect individual spaces in their respective regions; however, it’s been recommended that the circus world utilize services created for the rest of the arts.

- A fairly consistent comment among respondents was addressing pronouns, where nearly 10% of participants pointed out that it would be helpful to include nonbinary options in registration and among peers.

- Fair compensation and cost of circus/aerial training was highlighted in the qualitative responses. These responses indicate that circus as an industry has clear issues around fair compensation and barriers to entry due to both marketing/inclusivity and cost of training, particularly during the pandemic.

- Respondents emphasized that hiring bias in the circus world is a symptom of inequities faced upstream, rather than the cause of inequity itself. Therefore, some of the solutions proposed, from instituting quotas to funding marginalized groups, may not address the root causes these initiatives try to address.

- Respondents to the questionnaire were overwhelmingly white. It is difficult to determine concretely whether this is a reflection of circus makeup in North America in general, or a reflection of respondents reached by the survey (due to social media algorithms and the email lists). That said, judging by abundance of comments, respondents are hungry for education and clear policies that promote inclusion.

It is evident that participants are passionate about these issues and are willing to share their ideas. They recognize many symptoms of inequity and propose solutions to address the causes. Reopening studios, performance spaces, and circus companies may want to open dialogue around these issues and take these recommendations under consideration in order to create a more just, inclusive, equitable circus community post-pandemic.

Highlighted Responses

(Please refer to “Appendix B” for a full list of participants responses)

- Funding/support for circus works exploring the experience of minorities would be a great way to help others feel like there is room for them in these spaces. If I can’t see myself in the public image of “circus”, why would I think there’s a space for me within that community?

- I think that the goal of this policy of equality and inclusion is totally legitimate. It seems obvious to me! However, even though the problem has been correctly called out, I think it is overly simplistic to try to fix the situation by following quotas when casting for roles or creating new projects. Quotas could actually cause more harm than good, simply making us feel better about our actions…The problem, as we all know, starts much earlier: it is the result of inequalities in our society.

- There is constant body type, movement style, and even hair colour discrimination (lot of comments about blond & sexy being attractive for corporate gigs). To be able to fit in, you have to adapt to these standards. If you don’t, then you are labelled as “not a team member”, “not being able to adapt”, and “conflictive”

- Since my son is only [a child], I do want to share a micro aggression that occurred within this past month and hurt him so badly he quit the class. He has been a part of a circus for 4 years. He was invited to a zoom class with another circus and did not know this coach or have much of a relationship. 3 out of 4 classes the coach made a comment “tighten your back, you look like you’re breakdancing” He repeated “look like you’re breakdancing” three times in the final class where my son ended the class in tears. He is black with locks. There are no other black people in the class and breakdancing was not referred to any other student. What was the most painful out of all this was the lack of support from our circus community. When I suggested this coach might want to examine racial bias our circus defended the coach and dismissed the comment. Immediately defending the coach as “not racist” and yet we claim to be a social circus. The defending and invalidating reaction was absolutely the hardest part. Let’s do the work to examine our organization’s way of thinking and be open to our blind spots. As this experience and time is pointing out, people in power cannot know the blind spots until we are ready to accept they are there.

- Our theme for one of our student shows was set to be “around the world,” and each performer had to choose a country to represent with their costume and music choice. The performers felt weird about appropriating cultures, but also it would be odd for most of the countries to be European. The theme decision was made without consulting the POC on staff. There is also no clear communication about hiring procedures or promotion procedures. People just inquire about jobs and are hired or promoted if they are close with management. This tends to put women and POC at a disadvantage, since we tend to not to directly ask for things even if we have more experience than the people being promoted above us.

- Because circus is a recreational privilege, our most advanced students do tend to come from a background of wealth and are usually white. Our youth companies reflect students who can afford that (i.e. in finances, time, transportation, etc). It’s not a policy, but students go through an audition process, and are expected to be in class a certain number of times, or they will be penalized. We started a youth troupe specifically for students of color, or those on scholarship – but they are a part of our ‘outreach’ program and not our ‘performance program’.

- It’s frustrating to hear a hiring policy address race at all. We absolutely need to be hiring people of color, but why do you need to tell people that’s what you’re looking for? I’m a Latina woman, and I’ve been hired for an ethnic look. It completely undermines any confidence I have in my abilities. It makes it feel as though I was hired because they wanted to look diverse, not because they truly valued diversity. We absolutely need to be aware of who we’re hiring, but there’s no need to explicitly explain that to the person being hired.

- Allowing for incremental payment options for large studio/class fees and allowing for work trade at the studio helps make it available for a wide[r] range of people, which is so important given how financially unaccessible it can be. On a very small scale simply hiring teachers that come from different backgrounds and aren’t all thin, white, prestigiously trained makes a big impact on students being able to feel confident

- There aren’t many black or POC aerialists [in our area]. We have opened our casting up to other sideshow burlesque acts to diversify our shows. We have also considered having a quarterly BIPOC show and the producers make no money from it. We have also considered trading lessons but have struggled with undervaluing ourselves and the commitment to learning long enough to perform. When BIPOC do not apply for our shows, we specifically ask some BIPOC performers that know us well to advertise that we are looking to cast more BIPOC. We have also directly contacted performers to be in our shows. We also make sure we hire BIPOC MCs and photographers. We are completely transparent about how much money we make from shows, how it is divided, and who makes what money. Producers have taken huge pay cuts in order to pay performers fairly.

Special Thanks

We would like to acknowledge and appreciate the efforts of the following individuals and organizations, without whom this research would not have been possible:

- En Piste – National Circus Arts Alliance

- American Circus Educators

- Cynthia Platero

- Sarah Raillard

Footnotes

1. Nykolaiszyn, J. (2012), “The Circus in America: 1793‐1940”,Reference Reviews, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 50-50.

2. Survey was administered H ere on Google Forms

3. School CLimate Questionnaire found here

4. Translated by Sarah Louise-Raillard

5. All graphics and data visualization compiled by Cynthia Platero

All infographics and photos provided courtesy of Circus For Change. Main image Credit: Bethany Shao

.

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!