First of Its Kind: The Circus Buildings in Europe Conference

The Circus Buildings in Europe– International Academic Conference and Circus Buildings Exhibition made up the official opening to the 14th Budapest Circus Festival— and both events covered extensive ground. Conference moderator and Hungarian Circus Arts museum researcher David Könyöt takes us along the journey from the event’s planning to its final stage, including a run-down of the expert panelists and their findings.

The Circus Building Conference was the first event of its kind anywhere in the world. Originally, the idea came from Peter Fekete, the Hungarian Minister of State for Culture, who wanted to cover the topic of ‘The History and Fate of European Circus Buildings.’ The Conference concentrated on buildings in Western and Central Europe, including those that had been rebuilt, remodeled for another purpose, or destroyed; and the many that still function as circuses, examining how they reflect our social situation and the modern appreciation of circus arts.

Fekete tasked the head of the Museum of Hungarian Circus Arts, Ms. Emese Joó, with organizing the event. She was assisted by Susy Eötvös and Ancsa Könyöt Schneller, the international relations staff of the National Circus Arts Center, and myself.

Our first task to prepare for the conference was to compile a list of speakers and experts. We contacted many circus professionals, historians, and researchers, each of whom presented knowledge from different aspects of the conference topic. From those that accepted our invitation, we put together the final panel.

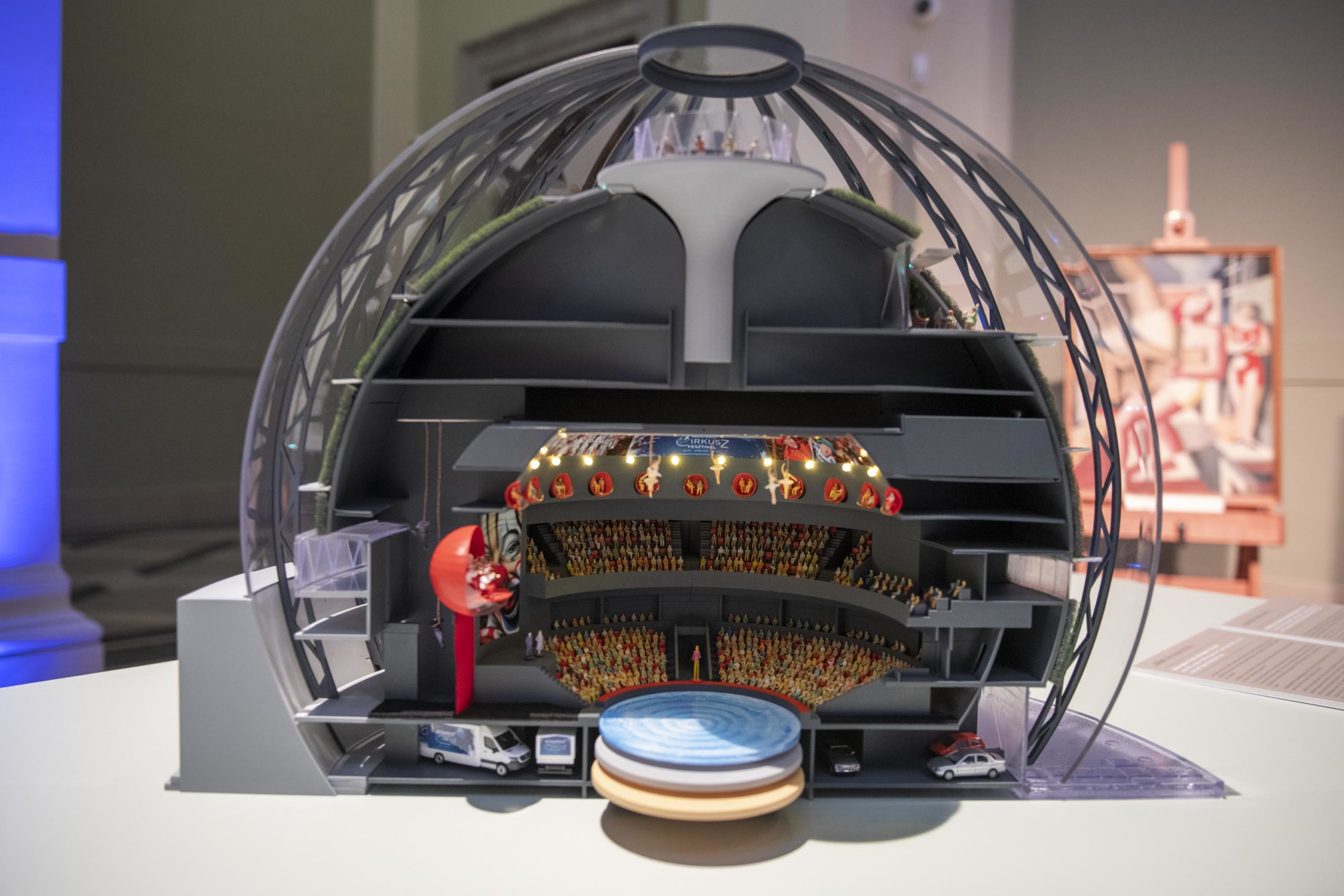

In conjunction with the Conference, museologist Szandra Szonday and archivist Mihály Szécsény curated a circus buildings exhibition using models, moquettes, technical drawings, and original prints of circus buildings. The exhibition also featured a new model of the building that will eventually replace the Budapest Capital Circus, which opened in 1889 and is the oldest working static circus in Central Europe. With the help of architect János Szabó, the exhibition started to take shape, with interactive digital displays and physical relief maps reflecting the subjects that the Conference speakers would discuss on the podium, giving everyone in attendance a starting point for joint discussions.

All of this work was done under the shadow of the pandemic: another logistical challenge for us organizers. Because of the Hungarian government’s efficient handling and clear safety guidelines, however, event restrictions were light. Mask-wearing and other safety protocols were properly observed throughout the entire Festival, and Conference visitors and guests were provided with sufficient information about the requirements for their entry into Hungary and their return home.

The Exhibition and Conference both made for a fitting opening to the 14th Budapest Circus Festival’s performance programmes. In establishing highly successful national and international collaborations between circus researchers, the Conference has reinforced the position of Hungary— and its National Circus Arts Centre— as a central hub of the European circus arts. This project was very special to all of us involved, and my appointment as conference moderator made me even more determined to ensure its success.

The Main Event

Our preparations for the Conference were all finished by 10 am on January 11th, when finally guests filled the room.The venue was the Museum of Fine Arts in Heroes Square: one of the most beautiful structures in Budapest, it was the ideal location to talk about circus buildings. As well, the event was livestreamed over social media by the Capital Circus technical team, who also offered Conference guests personal headsets with access to simultaneous translations in French, English, and Hungarian.

The Exhibition and Conference were opened by Peter Fekete, Hungarian Minister of State for Culture; Dr. Almássy Kornél, director of the Hungarian Museum of Architecture; and Dr. Alain Frere, founder of the Monte Carlo Circus Festival.

The panelists included a wide diversity of speakers. Each speaker was allotted 25-35 minutes for their presentation. France, which has the highest number of working circus buildings of any country in Western Europe, was the main topic of four speakers. Below are edited highlights from the Conference; full transcripts will be available on request.

Dr. Alain Frere, France

Artistic Director, Circus Researcher, and Founder of the Monte Carlo Circus Festival

Dr. Frere’s presentation concentrated on the ancient buildings of France, including the original Cirque Napoleon (built in 1852), commissioned by French Circus Director Louis DeJean. It is now famous as the Cirque d’Hiver Bouglione, Paris. He also gave a short commentary on his part in founding the Monte Carlo Circus Festival, praising the Royal Family of Monaco for their continued and enthusiastic sponsorship of the event.

.

* * *

History, Heritage, Future

Pascal Jacob, France

Circus Historian, Collector, and Author

Founded in 1768 England by the former cavalry officer Philip Astley, the modern circus, very early, on felt the need to protect its playground with buildings linked to its internal structure and 13-metre ring. Dozens of static circuses were established in the heart of major cities from the end of the 18th century. Following the arrival of circus tents, most of these circus buildings were destroyed between the late 19th century and the 1970s.

Since the last years of the 20th century, producers and designers have been reconnecting with the issues and parameters of the old stable circuses and implementing a new architectural vocabulary to create a new generation of buildings— places of both creation and dissemination. After Europe and North America, the most original buildings have come out of Asia, especially China. These buildings return to the basics, both structurally and artistically.

* * *

Opulence and Ostentation: 19th Century UK Circus Buildings

Opulence and Ostentation: 19th Century UK Circus Buildings

Dr. Steve Ward, UK

Social Historian and Author

Dr. Ward took the Conference on what he called a ‘Whistle Stop Tour’ of buildings long-forgotten and some hitherto unknown in Brighton, Liverpool, Dublin, Bristol, Birmingham, Manchester, and Glasgow. Many of these buildings have been renovated or repurposed over the years. Leeds in Yorkshire, England had 12 circus buildings, only two of brick construction, with the rest made from wood and canvas. One of those that survived is the Cirque and Grand Opera House of Belfast, built in 1895 on the site of a previous circus, Ginnets Olympia. It survives as the Grand Opera House, and after numerous alterations and renovations, it is now a general entertainment venue.

* * *

Memories of the Sofia State Circus Building

Memories of the Sofia State Circus Building

Dragomir Draganov, Bulgaria

Television Journalist

Draganov presented an emotional and well-received address on the history and sad demise of the State Circus Building in Sofia. The earliest data reports that a building was erected in 1888 for the Pizi travelling circus troupe. In the 1950s, the first state-owned wooden circus was bought from Romania by a pool of Bulgarian circus artists. This small but cozy building hosted circus shows, foreign singers, ballet troupes, and orchestras. Ice and water circuses were performed for the first time in Bulgaria. In 1962, a new building was commissioned with prefabricated sections and a special domed roof designed and built by the Stankov Family.

On September 23, 1983, tragedy struck when a fire engulfed the building. A carelessly thrown cigarette was said to have caused the outbreak. Artists tried to put out the fire with little success. The fire department arrived after 20 minutes, but neither their water tank nor the pressure in the hydrants was enough to fight the blaze. Suddenly the dome collapsed, and after 40 minutes, the building was no more. The only photographs of the event were taken by Ivan Grigorov of the ‘Pogled’ newspaper, who was then arrested, giving rise to rumors of a planned arson attack. Grigorov nonetheless managed to hide a single film reel with footage of the fire, but only showed the images many years later, following the democratic changes in 1989.

* * *

The Evolution of European Circus Buildings: a joint presentation

M. Dominique Denis and Jean Arnaud, France

Director of World Art and Director of Circus Promotion Agency

Taking turns at the microphone, Dominique and Jean gave a lively, entertaining presentation of many European buildings, providing essential information for researchers. Buildings discussed included:

- Circus Krone, Munich- Built out of wood and inaugurated in 1919 by Carl and Ida Krone, this circus was destroyed during the Second World War. It was later rebuilt in 1962.

- Cirque Royal de Bruxelles- designed by architect Wilhelm Kuhnen, this circus was Inaugurated on January 12, 1878. The building was a twenty-sided polygon, measuring 37 meters in diameter. It was also the site at which, in 1955, the Moscow Circus performed for the first time in Western Europe.

- Copenhagen Circus- This building opened in 1886 with a show from Ernst Renz. Willy, Ernst, and Oscar Schumann became its artistic directors in 1916. In 1938, Jean Houcke took the reins of this prestigious establishment of international renown, serving as its director until 1940. During the Second World War, the building’s management was entrusted to the Miehe Circus, then to Mikkenie-Strassburger. From 1969 to 1990, it was under the direction of Eli Benneweiss. It is now used for functions and dinner shows.

- Cirque d’Hiver, Paris- References to this building covered the same ground as presented by Dr. Alain Frere.

- Circus of Amiens- The municipal circus of Amiens was built from stone, brick, and iron by architect Emile Riquier. It was a 16-sided polygon, measuring 44 meters in diameter, with a periphery of 150 meters.

- The Circus of Douai- Opened on July 9, 1904, with the Ducos-Loyal troupe, directed by Annette Ducos. Since 1980, this establishment has become a center for cultural activities.

- Valenciennes Racecourse- Built in 1924, the building still exists, but it has been transformed into a supermarket.

- Cirque-théâtre d’Elbeuf- On September 4, 1892, Sam Lockart inaugurated this octagonal stone circus, which held 2,200 spectators. It has since been transformed into a cultural entertainment center with various shows.

- The Puy du Fou- Between Chambretaud and Epesses’ villages stands this magnificent Roman arena, which was built in 2001. At 115 meters long, this seemingly ancient stadium can accommodate 6,000 spectators. It is constructed out of concrete and synthetic materials, giving it the illusion of old stone. If it is not, strictly speaking, a traditional circus, it is nevertheless interpreted as one by artists, with beasts and chariot races. This grandiose show is organized by Philippe de Villiers.

- Circus of Châlons- The building was inaugurated in Châlons-en-Champagne on April 16, 1899. On May 3 the same year, the Cirque Vinella, directed by Achille Vinella, presented the great historical pantomime Cuba there. The circus was damaged during the Second World War and restored in 1946. In October 1985, the circus was assigned to the school known as the Higher Center for Circus Arts Training.

- Circus of Reims- Opened in 1865, this stone monument is inspired by the Cirque des Champs Elysées. It is built on a 16-sided polygon, inscribed inside a circle that is 33 meters in diameter. The building is 15 meters, or three stories, high, and its hall has 2,000 seats.

- Circus of Troyes- Opened on March 18, 1905, with the Cirque show by André Plège. The building is 18 meters high with a diameter of 35 meters. After 1938, the room became a cinema; in 1966, it was transformed into a Palais des Congrès. Four years later, it was fitted out to become the Théâtre de Champagne.

* * *

A Glimpse at French Stone Circuses Through Collectibles

M. Gilles Maignant, France

Collector and Circus Museum Director

Maignant’s presentation conveyed the history of stone circuses through a pictorial display of prints, drawings, posters, artifacts, and other collectibles.

.

.

.

* * *

Circus Buildings in Great Britain

Circus Buildings in Great Britain

Chris Barltrop, UK

Ringmaster, Historian, Author, and Performer

At first, circus shows took place in the open air. Long before the arrival of the Big Top or chapiteau, touring shows used portable structures made of wood, which were laborious and time-consuming to set up. In some cities, they instead erected more permanent wooden buildings, sometimes with roofs of cloth or canvas. The first of this type to be documented was Astley’s Royal Circus in Dublin.

In 1882, the circus proprietor Charlie Keith invented a ‘Portable Circus Building’ utilizing fold-out panels mounted on his vehicles. The touring proprietor, Frederick Charles Hengler, changed from tented shows to his permanent buildings, often featuring an arena that could be flooded for a water spectacle. Hengler’s Cirque in London’s West End presented circus entertainment, but that building was redesigned in 1909 to become the London Palladium, a variety theatre. From 1900, the London Hippodrome produced shows on stage, in a circus ring, and as a water spectacle, changing almost instantly from one medium to another during the same performance. In 1909, this abandoned circus also became a variety theatre. From 1903 to the present day, the Great Yarmouth Hippodrome Circus has continued a tradition of high-quality, innovative circus shows and features a water spectacle.

* * *

When Circus Entered History

Dr Paul Bouissac, France

Author and Professor Emeritus at the University of Toronto

Like all oral cultures and traditions, the circus did not leave an archaeological record behind. We find only elusive traces of its presence through allusions made in literary or judicial texts. However, this situation changed dramatically toward the end of the 18th century, when industrialization and urbanization offered circuses new economic opportunities to secure sizeable audiences with disposable income. Buildings exclusively devoted to circus performances were built in all major cities in Europe, and circuses then produced written and visual archives that can be historically documented. However, the structure of these new venues is markedly different from the spatial organization of urban architecture. They are in many respects at odds with the geometrical norms, creating a different kind of space. To illustrate this argument, Bouissac used the Blackpool Tower Circus in England as his example.

* * *

Models of the Capital Circus

Fanni Farkas, Hungary

Architect

Farkas presented a short pictorial display of the Capital Circus of Budapest, showing models of its various incarnations throughout the years.

* * *

History of the Capital Circus

Anna Klara Andor, Hungary

Cultural Heritage Studies Professional

Presenting over Zoom, Anna showcased pictures and diagrams that documented the historical aspect of the Capital Circus.

* * *

Stories of the Capital Circus

Mihaly Szécsényi, Hungary

Archivist and Historian

The final speaker of the Conference, Mihaly gave a comprehensive history of the Capital Circus, with stories of its construction, remodeling, and renovation throughout the years. Recent archival research proves that the first iron-structured corrugated tin building of the Budapest Capital Circus was brought to Budapest from Munich.

* * *

The Conference closed with a buffet and a champagne toast to its success, with talks to hold future events studying other aspects of the circus arts and heritage.

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!