Circus Bodies: Circus Bodies with Disabilities

After the inaugural Circus and Its Others conference in 2016, a series of articles was published in Performance Matters, a peer-reviewed journal. Dr. Tina Carter (Founder of Airhedz) contributed an essay, “Freaks No More: Rehistoricizing Disabled Circus Artists,” in which she uses the term disabled “to reflect both the medical and social models of disability as it is not only that the bodies of the artists bore impairments, but,” as she argues, “that the historians rendered them invisible and forgotten, therefore historically disabled by omission” (Carter). [1] Carter’s scholarly work centers around aerial performers with disabilities who toured and headlined shows, and yet have been overlooked in mainstream circus history. Memory and history define current perceptions, and Carter’s research unearths untold stories giving a needed foundation to present-day artists. Research such as Carter’s is one step toward inclusion which necessitates both the exhumation of lost stories and the need to unburden present identifiers laden with stereotypes.

Codified Virtuosity vs. Meeting People Where They Are At

A consistent thread through this Circus Bodies series has been how true inclusivity challenges mainstream perceptions of virtuosity. Circus disciplines have codified skills that signal “success,” but these skills are only available to a narrow portion of the population for a myriad of reasons. In a recent interview with Lisa B. Lewis (Founder, Omnium), she gave a comparison to dance saying that a multiplicity of forms were developed from ballet “because the original rigid structure didn’t apply to everyone, and other people were still virtuosic.” We agreed that only positive expansion to the art form can come from loosening the confines of what is perceived as virtuosic or successful.

To do this, circus must be accessible, and accessibility must permeate every facet of the circus sector: training, performances, online and in-person communication, and more. In a recent panel discussion, Devon Taylor, Creative Producer of Women’s Circus, Australia, noted that it’s about “meeting people where they are at.” This echoed what Amber Parker and I spoke about in Fat Circus Bodies. Parker described how she and a co-teacher adjusted aerial equipment to the person rather than imposing the ideals of codified circus skills as the only means to success.

When the pandemic hit, Taylor spoke about having a sudden and steep learning curve to make online material accessible to community members with disabilities, but moving activities online also was a form of accessibility. “We found a lot of our community who had physical disabilities in particular were able to fully engage. We had a series of master classes online, and I had direct feedback from participants who said, ‘I never would have come to this, I couldn’t have made it, [or] I couldn’t have justified the costs.’” A silver lining to the pandemic, for sure.

Dr. Kristy Seymour (Founder, Circus Stars) specifically works with youth on the autistic spectrum. Seymour notes, “For children with autism the practice of circus values their eccentricities, their individual preferences and talents while at the same time it encourages them to interact with and rely on other children and their circus trainers.” In a 2017 TED Talk, Seymour describes, “If a child has a preferred way of being in the world, that can often be incorporated into their training.” She describes the physical benefits of circus, the development of gross and fine motor skills, core strength, flexibility, and proprioception. “Circus provides the sensory embodiment that children on the autism spectrum so often seek. Circus is tactile. Since I’ve been using circus and autism together I have seen children go into amazing transformations. I have seen kids who have been highly agitated, anxious, and refusing to participate in class at all go to calm, focused, and adventurous by the end of the hour.”

Seymour met resistance when first proposing her curriculum, but since her research has robustly proved useful, “I now get recommendations rather than roadblocks from pediatricians physiotherapists, speech pathologists.” Her research has been added to Cirque du Monde and inspired circus as a therapeutic practice in an European autism special school. Conversely to the accessibility that Taylor’s community found during the pandemic, Seymour described how her students being disconnected from classes affected a vital part of their wellbeing. “[I]t’s not their recreational after school activity, it’s their therapy. And for a lot of them it is the thing that’s keeping the children together, it’s their one activity they will go to, it’s the one thing that is building their confidence that is stopping them from self harming, that is helping them deal with bullying.”

You have to normalize the marginalized in order for this to be just obvious to everyone. We need to get to the level in our society where we’ll [say], ‘Of course we’re going to accommodate you. It’s the right thing.’

Redefining Circus & Normalizing the Marginalized

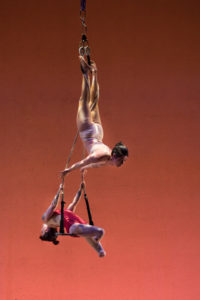

Extraordinary Bodies, a UK circus company, is a collaboration between Cirque Bijou and Diverse City. It is the UK’s “leading professional integrated circus company that creates large scale, bold, radical and joyous work with an exceptional cast of disabled and non-disabled circus artists, actors, dancers and musicians.” In a video in the About section of the company website Billy Alwen, Artistic Director, says that through their work they had to rethink what they meant by “circus.” Like codified virtuosity, the idea of rethinking or redefining gives the feeling that “circus” seems to hold fast to particular expectations that must be broken in favor of inclusivity.

Lewis described the same idea, “You have to normalize the marginalized in order for this to be just obvious to everyone. We need to get to the level in our society where we’ll [say], ‘Of course we’re going to accommodate you. It’s the right thing. Of course we’re going to do this. Why wouldn’t we?’ That’s the level our society needs to be at.” Claire Hodgson, Co-Founder of Extraordinary Bodies, offers, “Disabled people have historically been shown as vulnerable and fragile. Extraordinary Bodies shows disabled artists doing circus that requires immense strength and skill. It is a re-wirement of our culture. The truth is that all bodies are fragile and all bodies are strong.” Whether it’s marking up current definitions of circus with the proverbial red pen, or shifting conceptual understandings of the genre through modeling, Omnium and Extraordinary Bodies are rethinking, redefining, rewiring, and normalizing accessibility in circus.

Bridges

When considering accessibility, separating the facets of the circus sector–performing, audience, training, etc.–is impossible. Lewis visualized accessibility and inclusivity as bridges: bridges between students and training opportunities, between professionals and performing opportunities, and between performances and audiences. She said, “If you’re creating this brilliantly inspirational piece, and the people who need to be inspired, can’t get to it, this makes no sense!” Omnium, is a virtual, fully integrated and accessible circus show. “We have American Sign Language, we have audio description, we have plain language version. We’re currently re-editing our showcase our virtual version to include Spanish. Our live version will have the first ever in the country reduce sensory seating area for people that have sensory sensitivities, and autism.” She said it had been brewing for years, but the pandemic gave her, the creative team and the cast the push to make it a reality.

Lewis has decades long experience in creating accessible shows, specifically with Big Apple Circus’s Circus for the Senses. I asked her what considerations are necessary to create an accessible show. She recommended asking, “What do they [audience members] need as a bridge to be able to fully enjoy this experience? How do they perceive the world? What do they need to feel completely integrated into our society?” Although the social justice movement of the past year has brought inclusion and accessibility to the forefront of people’s minds in a new way, Lewis reminds that this is not new information. “You don’t have to make this stuff up. There’s a whole movement for it. It’s called the ADA [American Disabilities Act].” [2] There are professionals who can advise individuals or companies through the processes of making classes and performances accessible.

Accessibility & Support

Last fall I spoke with Bojana Coklyat, an Arts Access Consultant, about how to make online material accessible. She mentioned a few key elements: alt text should be included on all images and videos; capitalization should be paid attention to so that screen readers can accurately distinguish between words [3]; closed captioning for recordings and live captioning for streaming events; simple statements in marketing and advertising such as, “This is an accessible event”; making an avenue for interested attendees to contact a team member and let them know what they need; making the event sliding scale so it is economically accessible. Other excellent resources come from Ontario’s Kingston Circus Arts, a leading institution in inclusive circus practices. Their website has a page titled “Increasing Accessibility in Movement-Based Practices,” which offers guidance for instructors regarding preparations, in-class communication, and language. A full manual about creating accessibility in circus practices titled Flying Footless by Erin Ball and Vanessa Furlong, co-founders of LEGacy Circus, is also available through the site. Lewis described how consideration for inclusion goes far beyond classes and performances. Watching performers with disabilities breaks barriers, cultural (mis)perceptions, and can inspire, but there is also a real tangible, monetary ripple effect as well. Omnium is collaborating with Punkinfutz, a New York-based company that produces therapeutic toys, to design adaptive concessions which will be sold at future, live performances. [4] Such collaborations support tertiary institutions that value inclusivity. If accessibility and inclusivity are considered in each facet of the art form, then, as Lewis said, the marginalized will be normalized in both the art and the business sector.

To follow Dr. Carter’s lead and identify a population or individual ashistorically disabled also implies that there are those who arehistorically nondisabled and therefore benefit from the privilege of robust and positive historical narratives. Carter quotes Leonard J. Davis in noting that the omission of the history of “disabled performers highlights not only a loss to circus’s rich history but also the predominance of an ‘ableist culture,’” and her research “suggests that the nineteenth century was perhaps more diverse in its circus performers than has been remembered.” Carter concludes the article by stating, “The disabled circus artist, who is today considered a relative newcomer, can look back in time and see their precursors and challenge the conventions of the profession being solely for the nondisabled. The ring or stage should be more welcoming to disabled practitioners as circus artists and not merely social participants.”

Fortunately, history is malleable. Further research uncovering important stories will create a formidable foundation and powerful inspiration for present day and future artists and creators. And through repetition, what once was unfamiliar becomes common. Lewis reminds us that in order to “be the community we want to see,” we have to support each other: buy tickets to each other’s shows, show up, be part of the conversation. “Circus as an art form is mass entertainment… Our art form has the gift of being unified. Everybody wants to see it… And so to use that gift, to better our society: it’s our obligation. It’s the obligation of every performer, of every audience, of every human.”

Audio reading of this article:

Footnotes [1] Some communities use person-first language and others use identity-first language. Because the author is located in the United States, person-first language is used throughout this article, but some quotes or references may read otherwise. [2] An NPR article states, “Since 2000, 181 countries have passed disability civil rights laws inspired by the ADA, according to the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, a civil rights law and policy center.” [3] For example, Coklyat specifically mentioned that #blacklivesmatter will not be as clearly recognized as #BlackLivesMatter. [4] Adaptive items are any objects or tools that aid a person to complete an action of daily living. These may include sensory objects or toys that are specifically designed to stimulate the senses in order to create a calming sensation.

Resources Carter, Katrina. "Freaks No More: Rehistoricizing Disabled Circus Artists." Performance Matters, vol. 4, no. 1-2, 2018, https://performancematters-thejournal.com/index.php/pm/article/view/135. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Related Content: Extraordinary Bodies Circus Challenges Disability Stereotypes, Adaptive Circus Arts at Camputee 2019 with Erin Ball, Omnium Circus Brings Diversity to the Forefront–1st Online Spectacle on December 12th

Featured Image: Design by Emily Holt. Photo credits: Joel Deveraux, Marina Levitskaya, James Loudon, Gaby Merz, and Georges Ridel.

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!