The Ripple Effect of Continued Conversation: People of Color in Contemporary Circus

There is power in gathering. Storytelling, sharing ideas and laughter are tangible things. Currently, we are lucky to have virtual means to connect, yet there is no substitute for people sharing space and intention. While it remains uncertain when we will meet in groups again, I’m honored to reflect on a meaningful gathering that took place on November 6, 2019. The event, People of Color in Contemporary Circus, was a Long Table discussion hosted by Gibney Dance, a prominent dance institution in New York City. Core participants were Kiebpoli “Black*Acrobat” Calnek, burlesque performer Denae “Ravenessa” Hannah, Paris the Hip Hop Juggler, and Susan Voyticky, Artistic Director of Loki Circus Theater.

This is the third and final article of a series that is meant to continue the conversation. As Monique Martin,the event’s host and Director of Programming at Harlem Stage, said as we settled into the room, “There is no end, but there will be a conclusion.”

Earlier in the evening, we talked about the black body in public space, representation, permission to be sensual and access to and the use of culture. Much more was said than what this series of articles can summarize; highlights from the conversation have been extracted here.

Sometimes we paused, breathing, letting one facet of the conversation sink in before someone offered a new thought or story. I’m reminded now that breathing together is a privilege of gathering.

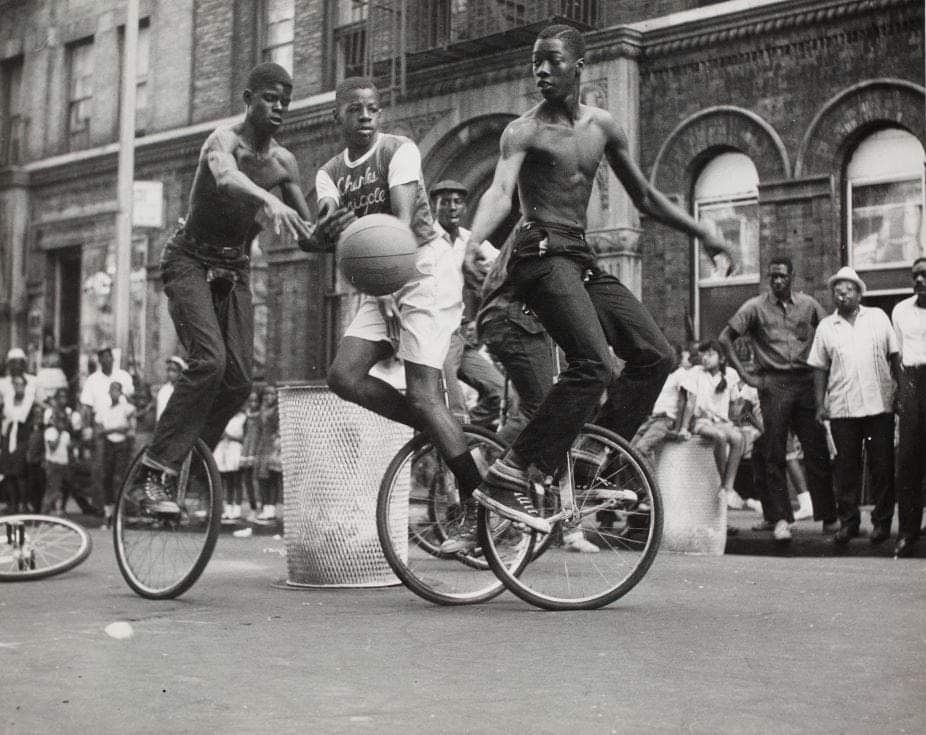

Kim Anthony Jones (Kip) (Director, King Charles Unicycle Troupe): I’ll try to paint a picture of how one man’s idea helped create a legacy for a group of young kids in an underprivileged neighborhood, and helped by teaching them discipline, direction, and character-building all through using unicycle as a tool.

Jerry King, at a very young age in 1918, snuck into the circus — what they called back then sneaking under the side walls. All he remembered was the elephant and the man on the unicycle riding on the high wire…. He always wondered back then why he as a kid never saw a colored kid riding on a unicycle. When he came upon a unicycle in a bicycle shop in the deep South, he was very fascinated with it. As he approached it, the shopkeeper kind of stood between him and the unicycle, and basically told him that kids of color don’t aspire to ride these kinds of exotic bikes.

Jerry grew up, went into the army, served in WWII. In 1942, he came out of the army and moved to the South Bronx and had his first son, Charles King. He remembered that passion that he had and took it. He taught his son Charles, in the hallway at 1400 Clinton Avenue in the Bronx, how to ride a unicycle. He did that because he was concerned about the social evils in the neighborhood — he wanted to try to steer his son away from that, but at the same time, he knew this unicycle was going to capture a lot of attention from the young kids in the neighborhood.

The next summer, Jerry took Charles out into the park where he showed all the kids in the neighborhood that he knew how to ride and some fascinating tricks. The whole neighborhood of kids just got hooked and wanted to learn how to unicycle. But there were some rules and principles that Mr. King set forward for these youngsters to learn how to unicycle. They had to sweep their blocks in the neighborhood, they had to obey their parents, they had to do well in school, they couldn’t curse, they couldn’t drink, they couldn’t smoke. If these kids wanted to ride the unicycle, they had to follow these rules that were set in place. It steered their character and steered them toward a different way of life from what they had seen. They started to do a lot of social neighborhood events. They started to do block parties and television shows. They then did the Jerry Lewis Show, and the Merve Griffin show. They got their first break in 1968, by auditioning on the sidewalks of Madison Square Garden for then producer Irving Feld of Ringling Bros., Barnum & Bailey circus. The next year, they were the first-ever all-black circus act to perform in Ringling.

It was a more social effect for Mr. King, because he was concerned for the kids in his own neighborhood as well as his own son. He took a passion that he was denied and helped uplift the kids in underprivileged neighborhoods where they lived. And they became a sensation. They were able to travel all around the world on one wheel, on one man’s idea. Sometimes just taking that one idea and helping that one person, that one kid, can take an idea farther.

We let the weight of this history, the ripple effect of a single person, settle in us. Where are circus stones being dropped now that will create new waves? Race, Gender and Women’s Studies departments and the fairly new academic field of Circus Studies were brought up. The potential for funding from universities circled us back around to how challenging it is, particularly in America, particularly as a minority, to get financial support for productions. And once work is produced, it must get booked, seen, and most importantly: reviewed.

Martin: Who’s going to review it? Who is qualified to review it?

Calnek: I don’t have the answer for that. I wish I did!… The shows that I produce are for me and for my community. It’s never for a white gaze… All my protagonists are queer, black women; love stories. I did a show called Quiet Come Dawn. I hired people who were not aerialists, not dancers, not theater people, but I knew they could play these characters… We created dancers, we created theater people, [they] rose to the occasion… we took years off before we produced our next one, and that’s what makes me nervous. We have to keep going. We can’t get defeated by the powers that be. Where’s our legacy that we can fund the next generation of artists? That’s my hope. Those reviews would help, also!(We laughed.)

Madeline Hoak (Associate Editor, Circus Talk): At an event last Monday, Sean Gandini said something interesting: we need to stop having conferences about circus or we’ll drown in an ocean of words! Everything I’m hearing tonight — the embodied practices, training, audience experience — makes me wonder about putting this embodied, experiential art form into language, which then becomes our history… I’m curious to hear your thoughts on that.

Voyticky: The more spaces the better. Let’s teach it to children. Let’s give it to kindergarteners. Let’s have it in classrooms. Let’s have a master’s in Circus Theory. The more that we can bring awareness to circus as an art form… as something we want to have supported both by individuals and by state, I think, the better… The more we can gather for next generations to have spaces for circus to live in: let’s do it.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa (Curatorial Director, Gibney Dance): It is about people. It’s about the accomplishments. It’s about the people who will be forgotten if we don’t have those words. I’m coming from a dance background trying desperately to find ways to put dance into words. More than the importance of describing what’s going on in the dance pieces is our treasured memory of what people have done. We’re talking here about people of color professionally, so that goes double and triple in significance for circus history to be recorded what we have done.

Ravenessa: When I’m backstage performers are live streaming…. It’s 2 am. The reviewers are not there to review that 2 am show! How can hashtags, technology be used to gather or source people’s self-documenting the movement?

The evening was getting on. Monique funneled us toward a conclusion, but not an end.

Monique: It’s an exciting time for American circus and all the hybrids in between. It’s an exciting time for people of color in contemporary circus… We just have to claim what is ours, what is new, and not be afraid to say, you know, we haven’t figured it all out yet… I think there’s so much more that we can chew on. I want to leave you with, as we talk about technology, are podcasts a way that we can have dialogue — to your point, this history and also this future of aspirations — about what we want to see happen with contemporary circus in this United States and with people of color in circus, in the world?

In the spirit of the Long Table discussion, I followed up with our core panelists to continue the conversation.

Hoak: What resonated with you?

Voyticky: It was wonderful to hear from a variety of artists of color… especially considering that circus in American culture is already considered outside of the mainstream art culture. So, in a sense, hearing from the fringe of the fringe.

Martin: The question of does the POC body take up more space? Physically and energetically. This was a compelling provocation to consider… I am still thinking about this as a consumer and a presenter….. Learning of [the King Charles Troupe] very unique history was fantastic. It also demonstrated… that there are many circus communities across the USA that are not aware of each other as there are not circus associations, which you find in other countries. These associations provide necessary advocacy… I’ve been thinking more intentionally and deeply around the specific challenges with POC’s in identifying funding and other resources in an already under-resourced genre.

Calnek: Legacy and how to continue creating more black acrobats to perform, teach, produce, direct and tell stories… I’ve been thinking a lot about what Maia said: what is being said, what isn’t being said, what you feel connected to maybe doesn’t match how you look… I wish we could have delved more into that.

Hoak: What topics did not come up during the session?

Paris: Systematic obstacles that people of color specifically tend to face in the industry. It’s not as overt as a Jim Crow era “Whites Only” sign in front of a theater, but I see it done in more modern ways such as efforts toward addressing diversity in a show or festival in seemingly every way possible except addressing the dearth of people of color. What’s sad is that in addition to the troubling optics, they’re missing out on culture.

Martin: POC’s in vaudeville, side shows, cabaret particularly during segregation. When POC’s began achieving more civil rights and opportunities, these jobs went out of vogue thus not propagating a next generation of artists.

Hoak: How can the conversation continue?

Martin: I’d like to hear more international voices at the table, i.e. Columbia, Mexico, Africa, indigenous Australians.

Paris: I hope…planners and organizers… can ask themselves three important questions [about people of color in programming and audiences]: “Where is there a shortage? Why is there a shortage? What can we do to fix it?”

Calnek: Training more people of color, more conversations — pockets of us getting together and then larger gatherings… Continuing the conversation in the living room, a podcast… And keep talking about the hard things that don’t get talked about. What if there was a monthly Long Table? Anyone can come. That’s the beauty of it.

Related content: People of Color in Contemporary Circus: A Long Table Discussion, People of Color in Contemporary Circus: Culture, Identity and Representation, The Queens of Hot Brown Honey are Finally Center Stage, The Role Queer Circus Plays, The Untold Story of Europe’s First Black Female Circus Star

Featured Image: King Charles Unicycle Troupe. Photo courtesy of Kim Anthony Jones (Kip).

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!