The Nomadic Immune System – Two Types of Circus Mobility Alternatives: Solutions from Taiwan

Being nomadic is part of the nature of the circus. Yet the era of the epidemic has exiled artistic and cultural workers who have interacted closely with institutions, venues and market mechanisms, throwing creatives squarely back into their very local lives.

Two kinds of actions emerged from these global events in Taiwan. One is the return of circus workers to the places where their skills originated, to rediscover connections and their relationship with everyday society. The second is to use the digital tools that have flourished with the epidemic to give circus, which is completely outside of daily physical techniques of the average person, a virtual body, and to debate this aesthetic boundary between the real and the virtual. Both of these actions seem to respond to the characteristics and strengths of the circus nomads: people roving the realm, or wandering into digital space.

The Nomad of Circus and the Return to the People

How to “return to the people and society” has always been one of the topics of Taiwanese performing arts. This contradictory and confusing topic ( Is art so far from society?) shows that the concept and education of current and contemporary performing artists in Taiwan has been influenced by Western forms and concepts for a long time. From the dancers of Legacy by Cloud Gate Dance Theatre(雲門舞集) who moved the stones of Xindian River for rehearsing in the late 1970s, to the Retrospective Project by U Theatre (優人神鼓)in late 1980s, and the Anˋ- Body Returning the Origin Project by Bare Feet Dance Theater (壞鞋子舞蹈劇場). In recent years, all have attempted to draw nutrients and transform their work into the creative vocabulary of contemporary art through a re-encounter with folk culture.

Huang Da-Yong (黃大湧), a clown doctor and a theater performer embarked on a road trip that intersected with life, creativity and performance around Taiwan with Taiwan Circus Gate(馬戲之門)during this Lunar New Year. The road trip was originally planned as a family trip to recharge and accumulate creative energy. But once his partner Wu Zheng-Ze (吳政澤) (Adam) joined him, and as the epidemic affected the Lunar New Year invitations, it eventually became a small nomadic trip for nearly ten people. The group started from Taipei, and landed in Nantou, Kaohsiung, Kenting, Taitung and Hualien, from an elementary school in an aboriginal tribe to Whampoa Military dependents’ village. They lived and performed together.

The unknowns are the people you meet, and the environment you encounter on the road.

“We practiced in the camping area and treated it as relocation training ”, said Yang Shi-Hao (楊世豪) of Taiwan Circus Gate, “I think it’s interesting to have different ways of opening the performance according to different spaces.” In addition to adapting to different spaces, they also have a more direct connection to the place through residents and schools. “We are all professionals in performances”, said Huang,”The unknowns are the people you meet, and the environment you encounter on the road. I will spend more time with the people and environment there.”

Lin Cheng-Tsung(林正宗), the founder of Thunar Circus (圓劇團), has begun his research on the body of Taiwanese folk acrobats even earlier. From Kaxabu! A Language No Longer Spoken? to Hung Tung’s Fantasy, he has continued to incorporate Taiwanese stories and colors into his works. Melancholy Mambo takes the funeral rituals Nong Naoas as its main field research object, and uses the ritualistic body which has the power to regulate the emotions of the mourners as the material for the performance. Recently, Lin and his artists cooperative are together learning the physical skills of the Leader of the Parade, including Song Jiang Team, Golden Lion Parade, and Stilt-Walking Parade. In the past few months, he has been spending at least eight to ten days a month in Tainan, moving from temple to temple, observing rehearsals and participating in tours. As the time of the annual parade and ceremonies is getting closer, he plans to stay in Tainan for at least 10 days every month in the future.

Lin Cheng-Tsung(林正宗), the founder of Thunar Circus (圓劇團), has begun his research on the body of Taiwanese folk acrobats even earlier. From Kaxabu! A Language No Longer Spoken? to Hung Tung’s Fantasy, he has continued to incorporate Taiwanese stories and colors into his works. Melancholy Mambo takes the funeral rituals Nong Naoas as its main field research object, and uses the ritualistic body which has the power to regulate the emotions of the mourners as the material for the performance. Recently, Lin and his artists cooperative are together learning the physical skills of the Leader of the Parade, including Song Jiang Team, Golden Lion Parade, and Stilt-Walking Parade. In the past few months, he has been spending at least eight to ten days a month in Tainan, moving from temple to temple, observing rehearsals and participating in tours. As the time of the annual parade and ceremonies is getting closer, he plans to stay in Tainan for at least 10 days every month in the future.

From his passion of love and promotion for contemporary circus in the past, Lin believes he thinks differently now: “To be honest, what I learned in the past all came from outside of the local context. We wanted to share it with the public, but it had no connection with them.” That’s also when he thought, “Why should I share circus with the people? What does it have to do with them? This is the bigger impact…..I’m looking for elements from what people say, from their bodies, from the point of view of the people and the land.” At the same time, he also observed that people’s participation in the arts may not be in the so-called arts and cultural activities, but in supporting the art of temple constructions, participating in parades in the community, etc. “The Parade is a kind of performing art for them, but also part of their identity, it’s a kind of cohesion.”

The Parade is a kind of performing art for them, but also part of their identity, it’s a kind of cohesion.

Lin Cheng-Kuan(林乘寬), a collaborator of Thunar Circus(圓劇團), reflected on the fact that he used to learn some traditional body techniques in school but did not have the possibility to use them on stage. “I think we need to be guided in this matter of transformation,” he said, “I think it is not always necessary to present a complete cultural framework when using a specific skill in performance, but rather the culture of the body will emerge naturally after internalization. As the body learns– or when you really touch on a level, the culture seems to slowly follow you…… I didn’t really want people to see it, but instead, someone gave me feedback that he actually saw it with my performance.”

Digital Escaping: The Image of the Galloping Figure

Is it possible for circus videos to develop a language of their own?

Since the epidemic, the digitization and online production of performing arts has become the focus of discussion in the industry. In terms of the many digital technologies, including virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), live performance filming or video production seems to be the more practical and budget-friendly option for everyone at the moment. Video works in the performing arts are not new. Dance videos have been around for decades and have developed their own aesthetics. In the past, circus performers used video technology mostly for documentation, especially after the emergence of self-media, video has become a medium for people to share their performance skills and moves.

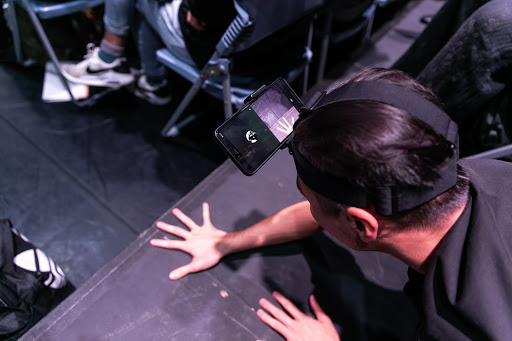

Lee Jun(李軍)and his team members presented a small video showing circus performers tumbling on the stage, stacking up in first-person perspectives during the final sharing of the Taipei Performing Arts Center’s Circus Factory Project at the end of last year. He then reveals how this seemingly real film was altered during the actual filming process. Lee said this idea came from an article discussing “Performance 2.0” after the outbreak of the epidemic last year. At the same time, because the video conference became a daily routine after the epidemic, he decided to use a more casual style to deal with this video. He said that the filming skill is much more difficult than he expected, and if he wants to shoot again in the future, he will look for collaborators who can master the video technology, so as to reduce the time spent on blind work.

When dancer Wu Cheng-En(吳承恩) and circus performers Huang Bo-Nan(黃博南) and Yang Jun-Yi(楊俊毅) collaborated on the video work The Air on the Other Side, they also found themselves at a disadvantage in terms of filming skills. So they decided to invite one of their friends who is a videographer to join them. Based on the personal experience of one of Wu’s friends who studied in Europe, The Air on the Other Side explores the loneliness of human existence from a cross-disciplinary perspective and the anti-physical principle of movement, presenting a dark humor style by breaking the rules of everyday life. Under the premise of not limiting or defining the genre of creation, both Wu and Huang believe that they have thus gained the freedom to create and play.

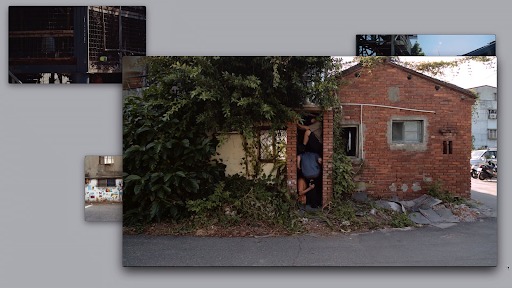

One of FOCA ‘s productions, Disappearing Island, which was nominated for the Taishin Arts Award last year, was also filmed as a circus video after its performance at the Taipei Arts Festival. The video version of Disappearing Island is not a performance recording, but a re-selection of the various movements of circus body interventions that FOCA has been developing on Shezi Island for the past three years. In addition to documenting the environment and a certain facet of site-specific creation through images, it also reinterprets the relationship between the body and urban space through the camera lens.

FOCA’s artistic director Lee Tsung-Hsuan (李宗軒) believes that the biggest advantage of video works is that they can link discontinuous time and space structures, regardless of the type of performing arts. At the same time, he also observed that circus performers have a high sensitivity to the frames produced by the camera lens because they have worked with objects for a long time. The camera is locked in a different area than the live performance, so the circus performers will adjust the scope of the performance, not only the height of the throwing props but also the positioning, the rhythm of the movements, the relationship between the performers themselves, all in that moment to fine-tune. He also expressed his hope to challenge more circus concepts through video productions in the future.

Wu Cheng-En’s video work The Air on the Other Side

Feature photo courtesy of Du Ma Xi. Huang Da-Yong, Wu Zheng-Ze and Taiwan Circus Gate performed at Whampoa Military dependents' village. Photo credit: ©Zhu Shan - JunEditor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!