Fragments from the Editors’ Note–Thinking (Through Circus) Together–A Book Giveaway

In times of climate catastrophe, refugee crises and Covid-19, the question of the responsibility that artists and scholars have is becoming increasingly urgent. What is the role of circus within society? How far does this form of art and entertainment correlate with historical and contemporary social interests? How does circus research position itself as a relevant field of research within academia in the 21st century? Those questions will be explored within the series Adventures in Circus Research–Facing a New Decade, curated by academic Dr. Franziska Trapp. By featuring circus researchers, we give them the space to explain the nature and significance of their research directly to the circus community and to highlight the practical impact of their research on the circus world and its relevance for society.

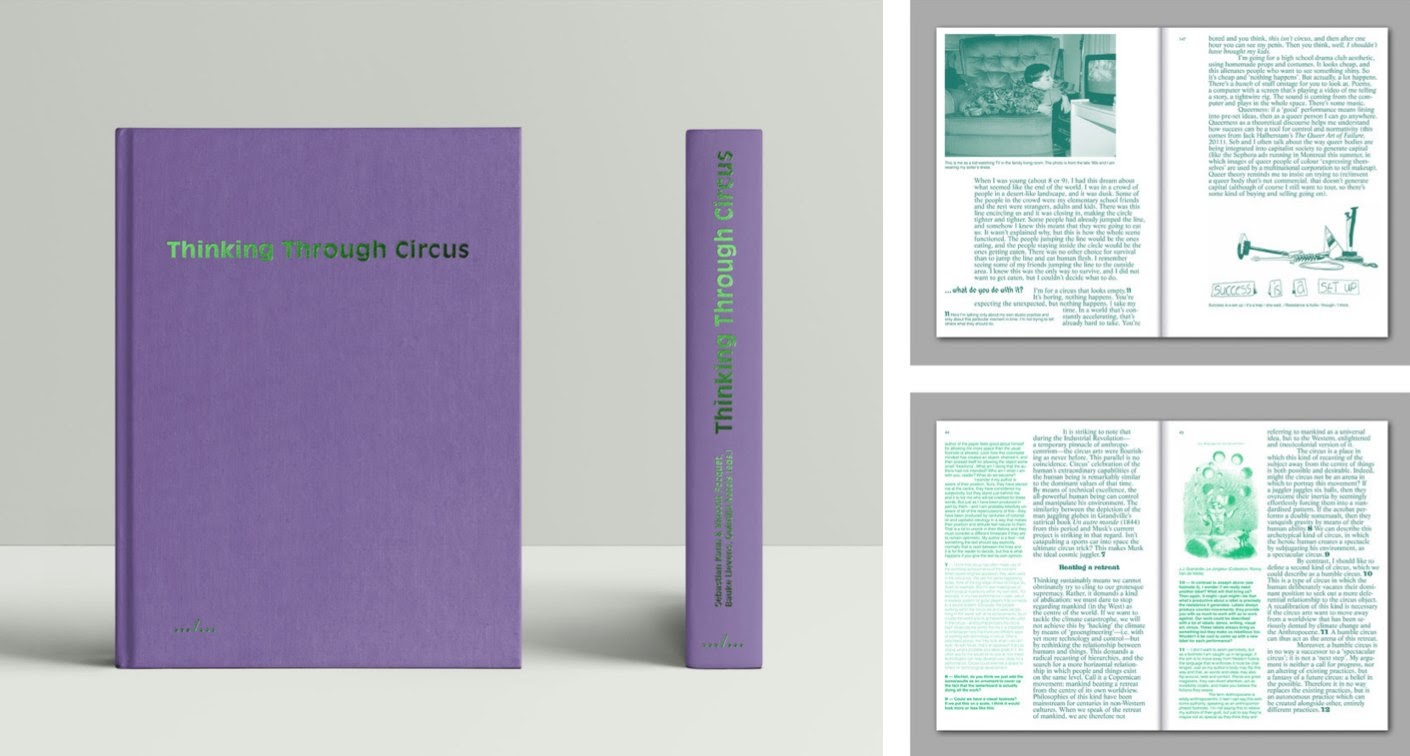

In this second article of the series, the four researchers Bauke Lievens, Quintijn Ketels, Sebastian Kann and Vincent Focquet, who collaborated on the research project The Circus Dialogues, share with us fragments from the editor’s note of their new book Thinking Through Circus: If we understand circus as an embodied thinking practice, what does it think? And how can circus as embodied thinking open up space to act?

Thinking starts from what they call a certain charme, a spark that lights up between people, turning them into friends. This friendship is not based on sharing the same ideas, but instead inheres in and arises from the momentum of having something to say to one another; such momentums result not only in thought, but also in thoughts that move.

– Maaike Bleeker, ‘Thinking No-One’s Thought’

Doing, thinking, doing

Thinking can happen without words. It can produce thoughts without language, unfolding in matter or in bodies. It can happen between a circus artist and an apparatus, for example. Or it can materialise as circus movement. Indeed, in circus we think through the body: through its corporeality we shape and perform relations, feelings, states and ideas. The physical practice of circus is, in that sense, an embodied thinking practice. Yet physical circus practice and thinking are often imagined to happen in separate spaces and at separate times. It is through this separation that circus tricks are worked and perceived as ‘thoughtless’ physical doings which can be filled with any meaning or content. Consequently, the thoughts and values already present and performed in the repertoire of circus disciplines become hidden from view and are made undiscussable.

Ours is a world in upheaval, and artists are actors in the public sphere. When we position ourselves in that sphere (e.g. when we make work), we do so by crafting what it is we want to share and perform. Circus tricks are never, therefore, neutral ‘doings’: each one is a proposition, a ‘thoughtful’ articulation of a particular relation between body and world, between instance and norm, and between performance and spectator.Thinking Through Circus wants to tend to these embodied relationships between contemporary circus and today’s world, defending circus as a field in which experimental thinking is already happening and can continue to happen. Doing so, we hope to contribute to a more sustainable circus, expanding both accountability and agency within our field.

Asking, dialoguing

Thinking Through Circus gathers ten dialogues with and between circus artists. Each entry bears witness to how a specific circus practice is (also) a practice of critical thinking. As the name of our artistic research project suggests, the thinking done in this book happens in and through dialogue. We consider dialogue to be inherently political: the ways in which we’re able to think together shape, to a great extent, what we’re able to do together (Bohm 2004). Conversely, the field of material possibilities of dialogue affects and delimits the thinkable and sayable. The spaces in which we think together, the constellations in which we do it, its temporalities and mediations: all of these elements shape the way we think together. Dialogue, then, is not simply about language: it, too, is an emphatically embodied practice.

This book came into being in the context of The Circus Dialogues, an artistic research project in which we, the four researchers and editors of this book, first found each other around questions of freedom and agency in the circus field of which we are part. As circus makers, performers and witnesses, each of us experiences recurring frictions (or even a certain violence) in our practices. Repeatedly encountering resistance while attempting to move forward, to create change, or to point out a problem (or even to just continue unchanged), we are bound to ask ourselves: why and how do we continue practicing? For whose benefit? And urgently: where can we find the space and energy to keep on keeping on?

So, we ask ourselves, what does circus hide in order to stage freedom?

Adopting the image of the ‘brick wall’, feminist scholar Sara Ahmed helps us to envision the blockages we discover within our field and institutions when attempting to challenge the norm. Especially in a field structured by narratives of freedom, both on and behind the stage, doing so can be hard work. We noticed that while circus performance often uses technical virtuosity to (re)present freedom, in reality, circus bodies tend to be(come) highly disciplined, normed, shaped, and sculpted by fixed (sometimes internalised) commands. At the foundation of the virtuoso body is a relation of domination that actually grants very little freedom. Moreover, the freedom that circus performance tends to stage through its focus on technical virtuosity often relies on the mastery of and control over things, animals and other bodies. These are just some of the myths of freedom from any social and physical constraint that (contemporary) circus continues to spin around itself, making the tacit disciplining that goes on harder to see. In a field invested in portraying itself and its artistic practices as an autonomous free zone on the fringes of society, some will even claim that these blockages don’t exist at all. This is why, according to Ahmed, brick walls are so hard: “You come up against what others do not see; and (this is even harder) you come up against what others are often invested in not seeing.” (2017, 138) So, we ask ourselves, what does circus hide in order to stage freedom? And, secondly, how are these brick walls maintained and held in place? Thinking Through Circus, then, is a collection of experimental encounters between circus practice and theory, each time guided by a few interwoven questions: What does contemporary circus do? What does it perform? What conventions and norms structure our field? How can critical thinking help us see beyond those norms? And, finally, how can both circus and critical thinking fuel our fantasies for the future, opening up space(s) to act?

A recurring question in these texts is: what would it mean to imagine circus practice as something sustainable in the long term, especially in the face of the troubles and blockages we encounter? While no one answer is given, what emerges is a specific ethic of perseverance, conjoining pure stick-to-it-iveness with deep sensitivity to the broader ecology in which that perseverance is enacted. ‘Staying with the trouble’ (as Donna Haraway would have it) – not turning away from or abandoning what causes friction, what’s messy, painful or discouraging – is for many here a working method, a way of caring (for circus) from within.

Worlding, tuning, relating

The authors of this book sketch the outlines of other possible circuses and, by extension, of other possible worlds. They do so using fantasy, poetry, and poetic imagery, making alternatives tangible. These speculations sometimes take shape through a gesture of gathering, dismantling the elements of what hurts and rearranging them in a more affirmative constellation. Sustainability, care, tuning and relationality are prioritised within these ‘worldings’, and the notion of agency is repeatedly rearranged. While circus traditionally puts the (white, male) human at the centre of the ring, in many of these texts, this centrality is reconsidered. While some writers have criticised the way circus artists appear to ‘dominate’ their apparatuses, this book attests to a variety of post-human strategies, adopted as lenses through which the relation between humans and more-than-human others can be experienced afresh. However, this is not the only way these texts attempt to redistribute agency among the circus field. Agency is fought for in other domains, ranging from neoliberal working conditions to gender.

Expanding: doing

The Circus Dialogues started out with a shared concern around questions of freedom and agency within circus as a field and an artistic practice. And indeed, agency remained central to our research, a concern underlying the ethical thrust of the thinking practices gathered in these pages. Agency: one’s context-specific ability to do. Agency is the space that is granted, it is the relative degree of one’s wiggle room. When we expose and critique the blockages we experience in circus, we are discussing the limitation of agency through the imposition of a norm. When we speculate about the circus of the future – and when that dream is a good dream – we expand the scope of the imaginable, prefiguring an expansion of the possible. When we meet in dialogue, training our imaginations to ‘go visiting’ someone else’s practice, we construct temporary, shared spaces in which something new or different becomes possible. We find ‘temporary beliefs’, we find shelters; we are temporarily dispossessed by a vision of the unexpected, or surprised by an ability we didn’t know we had. To us, both the writing of this book and the thoughts that emerge within it are attempts at making more wiggle room, expanding our ability to act in the circus field and in this world. We hope that with Thinking Through Circus we can make a gesture of affirmative criticality by which you, the reader, will feel empowered to build more future circuses, more future worlds.

For the Giveaway: Go to CircusTalk's Instagram to participate in the book giveaway of Circus Dialoguess Thinking Through Circus from June 29th to July 6th.

Feature photo courtesy of The Circus Dialogues. The author portraits were taken during a value exercise in the framework of the Third Encounter in PAF (April, 2018) Credit: Jakob Rosseel

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!