Does the Bechdel Test Have a Place in Circus?

There is nothing more satisfying than walking out of theatre having been inspired by an amazing circus show. However, a conversation we increasingly find ourselves having in post show conversations is the role of women in circus and the way they are represented. There have been incredible, strong, stereotype-defying women in circus for as long as there has been circus ,and their commitment to claiming space on stage cannot be overlooked. Nevertheless, whilst viewing a performance at the Mullumbimby Circus Festival, Charice raised the question of whether or not the show would pass the Bechdel Test. This began a discussion between us about the need for a framework to interrogate and understand female representation in circus today.

If you haven’t heard of the Bechdel test before, it is a set of three very simple rules that are most typically applied in the world of cinema, first seen in the comic by illustrator Alison Bechdel Dykes to Watch Out For. The test is used to assess how much and what quality of screen time women receive in any given film. To pass the test a film:

- Has to have at least two [named*] women in it

- Who have a conversation with each other

- About something other than a man

To give you some perspective, www.bechdel.io found that of the 2015 Academy Awards only 38.46% of films nominated for an award passed the test. Of course, such a simple test is by no means claiming to tell if a film is feminist, has interesting female characters or even attests to the overall quality of the film. What it does do however, is spark a conversation around the sexism in the entertainment industry, and with so many films being unable to pass such a low bar, it pinpoints the lack of representation of women.

While the Bechdel test has been mainly used to analyse films, we are reaching a time when producers of circus shows need to start examining the way in which they create works and how accidental dramaturgy can be interpreted by the audience. Circus is increasingly moving into the realm of high art, and with this comes the expectation that creators will think more deeply about the work they are creating. As Mitch Jones discusses in his article Creating Meaningful Contemporary Circus, creators of circus need to be aware that audiences are learning to read the contemporary art form and to find meaning in what the ensemble does. This means that acrobatics on stage have significance beyond physical tricks that will be read dramaturgically.

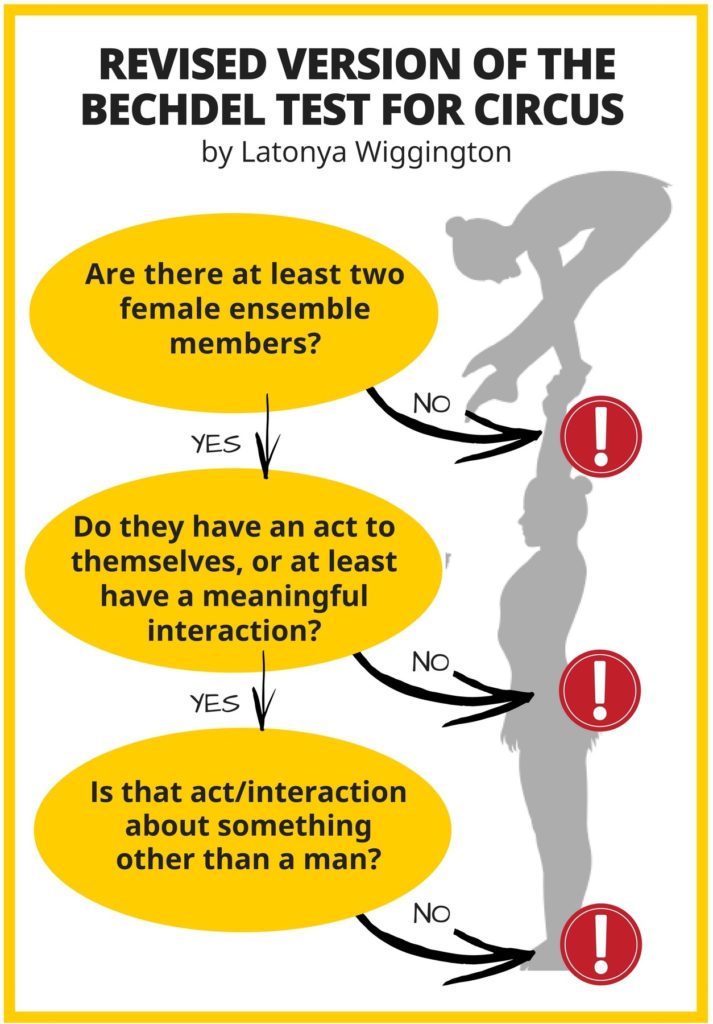

Applying something like the Bechdel test to a circus show can be quite difficult, as it is uncommon for circus artists to speak at all on stage. For that reason, here is a slightly revised version of the test for circus (see image).

In this way, a “conversation” was taken to mean a physical conversation or a distinct interaction on stage. For example, a female adagio pair performing an act would constitute the circus equivalent of a conversation. If that act was a about two women and their friendship, then the show would also pass step three, as the act wasn’t about a man. Instead, if their act was about competing for the attention of a male performer– then this hypothetical show would have failed the Bechdel test. With this version of the Bechdel test in mind, we examined some of the shows performed in Australia in 2017.

In some cases, it is easy to see whether a show has passed the Bechdel Test. For example, Rouge a recent production by Highwire Entertainment, which played at the Wonderland Speigletent in November. Rouge is a sexy, adult cabaret that features an act by female hand balancer Annalise Moore. In the act, Moore is supported by the two other female cast members Tara Silcock and Isabel Hertaeg. The act explores themes of female identity and sexuality and therefore passes all three steps in the test.

For the most part, Rouge is a fairly standard cabaret with acts that are flashy and funny rather than political. However, it is clear that the director, Elena Kirschbaum, has also considered how the performers are represented in the wider world of gender politics. This has resulted in a show that not only has a cast that is 1:1 female to male ratio but that also explores gender and circus roles in unexpected ways. The show even includes its own nod to another feminist device, the sexy lamp test, which examines whether a female character could be replaced with a sexy lamp without affecting the story line. In the show, Silcock has an early act as a lonesome sexy lamp unable to move freely or take initiative. However, as the show progresses she returns to the stage in an act that shows her taking control of her own sexual desires.

Backbone is the explosive new work by Gravity and Other Myths that premiered at the Adelaide Fringe Festival and was also performed at the Melbourne Fringe Festival.There is no denying that Gravity and Other Myths is at the forefront of Australian acrobatic performance, with a world class cast that truly owns the stage in terms of physical prowess and personality. Their show Backbone, however, does not pass the Bechdel Test.

The show’s director Darcy Grant states, “…it examines strength. Honestly, ironically, and personally” (cited in Rodda n.d.). However, in a show touted to examine strength, there doesn’t seem to be any real representation of female power. For example, both Jascha Boyce and Mieke Lizotte have major acts in which they are limp ragdolls, not moving their limbs themselves– instead they are manipulated by the male members of the ensemble.

In a further scene the male ensemble members lower a giant pile of rocks onto the women, literally limiting their ability to claim space on the stage. Whilst this might be seen as an ironic examination on Grant’s part, as a metaphor for womens’ space in the world today, it doesn’t read that way. Instead it feels as though the rocks lowering onto the performers were added for the visual effect and to build tension without thinking of the dramaturgical implications. The result is that the women do not have an interaction to themselves without the involvement of the men, which therefore fails Step two of the test.

Naturally, the Bechdel Test is not without its limitations, and this is even more apparent when it is applied to circus. For many productions it is harder to determine a clear pass or fail. For example, Driftwood by Casus does have at least two female performers that have a vibrant presence in the five member ensemble. They perform a lovely duo trapeze act together, free from male involvement – an incredibly refreshing moment where the audience can enjoy watching women relating to each other, thereby completing step three. However, the piece acts as a lead in for a male trapeze solo moment. So in considering step three of the test, it appears that the “conversation” of the two women is related to or about the male performer. Of course, this is a just one reading, and highlights one of the larger failings of the Bechdel Test in circus.

Contemporary circus as an art form rarely has clearly defined characters, roles or narratives making it difficult to apply such a simple test to a show. It also misses acknowledging the other areas a show might excel in such as representation of acrobats of colour, LGBTQIA acrobats, or acrobats with a disability. For example, while Driftwood may fall short of the Bechdel Test, it excels at positive portrayals of LGBTQIA relationships and contemporary portrayal of Polynesian culture.

This will always be the limitation of a simple set of rules, the goal is not to enforce the test on every circus company, nor to limit the enjoyment of any performance. Instead, a tool like the Bechdel Test should be used by creators and audience members alike to start thinking more critically about work that is produced in the circus industry and to be aware of the greater world of art, history and politics that circus performance stands in.

So, in the end, what does it matter if a show has passed or failed? Backbone, the only decisive fail in this list, was nominated for three Helpmann awards. Yet the ratio and roles of men and women in circus has meaning and inadvertently influences audience perspectives. On stage contemporary circus performers inhabit an imagined world that is similar to our own. It is therefore strange that some new circus ensembles can’t imagine women having an equal and active presence in that world. Female acrobats should be involved in the actions that have agency in circus choreography as well as being allowed to occupy and claim space on stage without being cramped out by male ensemble performers. Directors and performers both need to be aware that neglecting the consideration of dramaturgy with respect to gender risks perpetuating a tired and patriarchal representation of women.

This awareness can be seen in the work of artists with a passion for exploration who move beyond traditional gender and circus roles to create work that does not rely on preconceived notions of how a circus show should work. When this sort of experimentation is present it results in work that inspires, awes and adds to the overall conversation of women in the arts today.

Charice Rust, co-author, is a circus artist and co-founder of One Fell Swoop Circus. She is passionate about hanging by her arms and challenging expectations, explicit or otherwise, of what female performers are capable of.

Editor's Note: At StageLync, an international platform for the performing arts, we celebrate the diversity of our writers' backgrounds. We recognize and support their choice to use either American or British English in their articles, respecting their individual preferences and origins. This policy allows us to embrace a wide range of linguistic expressions, enriching our content and reflecting the global nature of our community.

🎧 Join us on the StageLync Podcast for inspiring stories from the world of performing arts! Tune in to hear from the creative minds who bring magic to life, both onstage and behind the scenes. 🎙️ 👉 Listen now!